Katharine Birbalsingh is the media-savvy headmistress of Michaela – a successful London charter school often described as the “strictest school in Britain”. During a meeting of parliament’s Science and Technology Committee last week, she was asked why girls are “not choosing physics in the same proportion as boys”. (About 4% of girls take A-level physics, compared to 17% of boys, meaning that boys make up about 80% of physics students.)

On this occasion, Birbalsingh made the “mistake” of not blaming the widely observed disparity on outdated and damaging stereotypes. Rather, she said, “I just think they don’t like it. There’s a lot of hard maths in there that I think they would rather not do.” When pressed on why girls “would not want to do hard maths any more than boys”, she said the research generally suggests that it’s “just a natural thing”. A natural thing? But that would mean… something terrible. (I’m kidding.)

As you might expect, Birbalsingh’s answer caused a bit of a brouhaha. Numerous commentators “called her out” for perpetuating those outdated stereotypes – outdated, I tell you!

Hayaatun Sillem, chief executive of the Royal Academy of Engineering, described Birbalsingh’s comments as “very disappointing”. Michele Dougherty, head of the physics department at Imperial College London, called them “astounding”. Becky Parker, visiting professor of physics at Queen Mary University, said they made her “shudder with disbelief”. Emma Bunce, president of the Royal Astronomical Society, admitted to being “shocked and deeply concerned”. Hannah Russell, chief executive of the Association for Science Education, said she was “very disappointed”.

There was also a cringeworthy Twitter thread from the official account of Imperial College London, which began: “NEWS FLASH! It’s not a dislike of “hard maths” that puts girls off studying or pursuing careers in maths + physics … It’s outdated and damaging stereotypes that close doors on many talented girls and women … Ready to hear about some of our most inspiring women physicists?” (In case you were wondering, the thread didn’t refer to any scientific studies.)

Birbalsingh’s answer was by no means perfect. For one thing, she attributed girl’s comparative lack of interest in physics to “hard maths”. And while it’s true that boys like maths more than girls (or, rather, dislike it less), the percentage of girls studying maths at A-Level is actually higher than the percentage of girls studying physics – by about 14 percentage points. And since maths involves more maths than physics does, if Birbalsingh were right, you’d expect the percentage of girls to be lower in maths.

Here’s what she could have said: “It’s not entirely clear why fewer girls choose to study physics. There’s a lot of evidence that boys and girls have different innate preferences, with boys being more interested in things and girls being more interested in people. It’s therefore possible that fewer girls opt for physics because they’re less interested in the subject. However, cultural factors may also play a role.” This might have sparked less of a backlash. (Perhaps, at the very least, fewer critics would have “shuddered in disbelief”.)

In Birbalsingh’s defence, she did subsequently pen an article for the Telegraph where she wrote that girls might be less inclined to choose physics “because girls are more inclined to be empathetic while boys are more systematic, as a large quantity of evidence suggests” (a more satisfactory explanation than “they don’t like it”). She also acknowledged that “I could have been clearer in my language”.

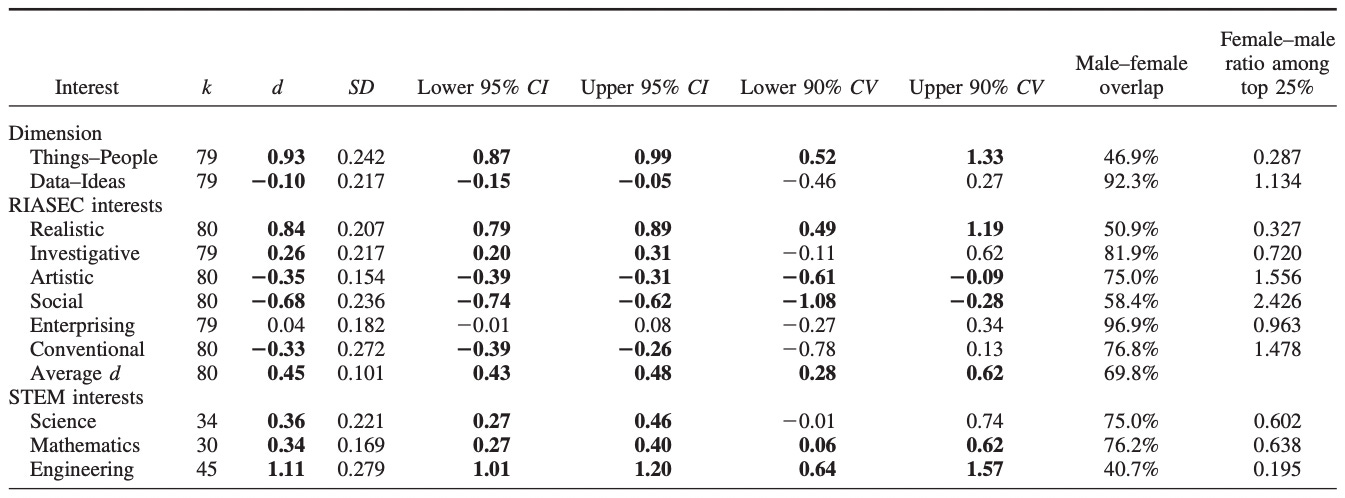

So what’s the evidence for innate sex differences in preferences? We can begin with the 2009 paper ‘Men and things, women and people: a meta-analysis of sex differences in interests’. Rong Su and colleagues analysed a large number of samples in which men and women had been asked about their occupational interests. (They’d been asked to tick statements such as, “I like to build things” or “I like to work in teams”.) The authors were able to calculate men and women’s average scores along a “Things–People” dimension, based on a formula that weights statements by whether they represent a preference for things-oriented or people-oriented work (see p. 54 here).

Su and colleagues’ results are shown below. They found a standardised difference of 0.93 along the Things–People dimension, meaning that men were almost 1 standard deviation more likely to prefer working with things (machines, gadgets, systems etc.). This constitutes a large effect size. As you can see by casting your eyes over to the final column, it means that in the top 25% of the Things–People distribution, there are only 0.287 women for every man; so the top quartile is 78% male. And note that the sex difference in engineering interest was even larger.

In a study published the following year, Richard Lippa analysed data from a large cross-national survey on gender differences, which was originally carried out by the BBC. Over 200,000 people answered the survey, and there were 53 countries with at least 90 respondents. Lippa found that in 53 out of 53 countries, men scored higher on the Things–People dimension than women; there wasn’t a single country where the sex difference was reversed. What’s more, the average standardised difference was larger than in Su and colleagues’ meta-analysis (d = 1.4).

Okay, so men say they’re more interested in working with things, and women say they’re more interested in working with people. But couldn’t these differences be due to those pesky stereotypes I mentioned? Perhaps society discourages women from being interested in things, and tells them to work with people instead. If it weren’t for the widespread belief that “physics is for boys”, maybe we’d see many more girls studying physics.

I’m not convinced. While such beliefs may contribute to girls’ lack of interest in the subject, it’s very unlikely we’d get to gender parity in their absence. In other words, even if society made every possible effort to dismantle stereotypes about who should study what, I suspect the percentage of girls in the physics classroom would still be less than 50% – probably much less.

Several lines of evidence converge on the idea that sex differences in preferences are partly, or indeed largely, innate. First, there’s the so-called gender equality paradox. This is the finding that gender differences in occupational interests are greater in more gender-egalitarian countries. (The percentage of female STEM graduates is higher in Saudi Arabia than in Sweden.) It’s not entirely clear what accounts for this result, and some researchers have questioned how robust it is, but what is clear is that there’s no evidence gender equality leads to less occupational sex segregation.

So if you were thinking “all we have to do is make Britain like Sweden, and the male skew of physics will go away”, you’d be wrong. In fact, if you want the male skew of physics to go away, you’re be better off making Britain like Saudi Arabia.

Next, there’s the evidence from studies of early infancy. According to a 2012 literature review, infant girls stare longer at objects with human attributes (such as dolls), whereas infant boys stare longer at mechanical objects (e.g., trucks and mechanical mobiles). Such findings don’t prove that sex differences are innate, but it’s difficult to see how they could be explained by socialisation. Babies are unlikely to have spent their first few weeks of life imbibing gender stereotypes.

There’s also the evidence from hormones. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia is a rare, genetic condition in which individuals are exposed to high levels of male sex hormones in the womb. Studies find that girls with this condition tend to have more male-typical toy preferences. Compared to matched controls or unaffected female relatives, they’re more likely to show an interest in trucks, and less likely to show an interest in dolls. Once again, this evidence isn’t dispositive, but it’s hard to explain by invoking socialisation.

Finally, there’s the evidence from non-human primate species. At least three studies based on primates have found that females’ preferences resemble those of female human children. Elizabeth Simpson and colleagues observed newborn macaques, and found that females showed greater interest in conspecifics’ faces. Gerianne Alexander and Melissa Hines observed green monkeys, and found that males spent more time with trucks, whereas females spent more time with dolls. This finding was then replicated by Janice Hassett and colleagues, who found that male rhesus monkeys had more interactions with wheeled toys, whereas females had more interactions with plush toys.

The evidence discussed in the preceding paragraphs suggests there are innate sex differences in preferences, though it doesn’t tell us how big they are. Indeed, the studies on early infancy, hormones and non-human primates were based on a rather crude proxy for subject preferences, namely interest in particular types of toys. And it’s not clear how the latter translates into the former. For example, if girls are 1 standard deviation less likely to pick the male-typical toy, does that mean they’re 1 standard deviation “innately” less interested in physics? Probably not. But I don’t know how the conversion should be done.

Nonetheless, if we assume the average difference along the Things–People dimension reported by Su and colleagues is innate, then we can explain basically all of the gender gap in inclination to study physics at A-Level. The top quartile of that distribution is about 80% male – the same as A-Level physics – and it’s not unreasonable to suppose that only people scoring in the top quartile would be interested enough to take the subject at A-Level.

Okay, you might say, but that calculation still rests on some pretty shaky assumptions. And even if gender parity isn’t a realistic goal, we might be able to get to 70–30 or maybe even 60–40. Anyway, what’s the harm in encouraging more girls to study physics?

To that, I would say: “Fair enough, physics is a rigorous subject, and we should be encouraging more young people to study rigorous subjects – rather than dubious ones like media studies”. However, we shouldn’t care about the gender gap in who’s studying those subjects. We should be encouraging more girls, and more boys, to study physics. (Recall that only 17% of boys take the subject at A-Level.) And if our efforts at encouragement result in the gender gap staying the same, then so be it.

Having said that, there is a potential downside in encouraging more girls to study physics: they might not actually like the subject, and hence may come to regret their decision later. (They might discover they’d have been better off studying Latin or biology, for example.) It hardly needs saying that individual students’ well-being is more important than the aggregate statistic “percentage of A-Level physics students who are girls”. In fact, the aggregate statistic “percentage of A-Level physics students who are girls” isn’t important at all. It’s just not something we should care about.

I would also raise the point that Susan Pinker has made: why do we take for granted that male preferences are the “correct” ones – that women would be better off if they were more like men? For example, women tend to prefer jobs that are less highly paid but have more-flexible working hours. As a result, when we calculate an overall “gender pay gap”, they appear to be worse off. But maybe men are worse off. If we calculated an overall “working hours flexibility gap”, we’d find that men do worse than women. And who’s to say that higher pay is “better” than flexible working hours?

It’s the same with A-Level subjects – well, almost the same. I’d certainly prefer girls to take a rigorous subject like physics than a dubious subject like media studies. But if we’re comparing among rigorous subjects – physics versus Latin or biology, say – there’s no obvious reason why it’s “better” to study physics, why the male preference is the “correct” one. I say this as someone who has female-typical preferences: I prefer biology to physics, and value flexible working hours over higher pay.

To sum up: Birbalsingh’s answer could have been better, but it didn’t justify all the histrionics that followed. And in any case, she clarified her views in an article the next day. While cultural factors may contribute to the gender gap in who studies physics at A-Level, innate sex differences in interests probably account for most of it. Finally, we should encourage more young people of both genders to study physics – because it’s a rigorous subject. But we shouldn’t care about the gender gap per se.

Image: Benjamin Couprie, 1927 Solvay Conference on Quantum Mechanics, 1927

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

Thanks for this. I am told she was being asked about the figures for her particular school, not in general. In the light of the general issue this is not important, but it explains why she gave the answer she did, because she very probably knows what her girls said to her about their choices.

On the broader front, I too don't want to encourage "girls to do X" or "boys to do y". Students should balance their interests against what society needs. Perhaps we need only a few physicists (and only the outstanding ones) but have a more pressing need for biologists, medics, nurses.

However, if everyone were taught the basics of thermodynamics, a lot of silliness could be avoided.

"Things–People distribution, there are only 0.287 women for every man; so the top quartile is 78% male.” Pedantic Point: it’s 71.3%.....

That aside, I enjoyed the article! Glad to see the Swedish data. Which I’ve seen before. Interesting, that when women are in a gender neutral society they tend to choose the more classically “feminine” jobs than do women in less equal societies. That’s one needs a bit more widely spreading....

Also: why no struggle for gender parity in the dirty and dangerous jobs? Sewer workers, rat catchers and the like? I always wonder about that.

Also: what about when women > men in a particular area. Should we worry about *that*?? If not, why not? There are more women in ballet.... and Women already outnumber men in many College courses. Hmmm?