NOTE: I now write for Aporia Magazine. Please sign up there!

Since Russia’s invasion began, there’s been no shortage of images of the physical destruction it has wrought: collapsed bridges, crumbling churches, street after street of burnt out buildings. The World Bank estimates that reconstruction costs may reach $349 billion. And that figure was published back in September, before the attacks on Ukraine’s critical infrastructure really got going. (To put it into context, Ukraine’s pre-war GDP was around $200 billion.)

One impact of the war that’s received somewhat less attention, but is arguably more important as regards Ukraine’s long-term future, concerns demography.

The UN reports that more than eight million Ukrainians are currently residing in other countries, having left as a result of the war. This represents around one fifth of Ukraine’s pre-war population. There are just under three million in Russia, just over five million in Europe, and a further 250,000 in North America. (The figure for Russia may comprise all of those who’ve gone there since 2014; it’s not entirely clear).

Now, if these eight million were a random sample of Ukrainians, the only effect of their departure would be to reduce the country’s population by 20%. Having a smaller population is worse in some respects: it curtails your military power, all else being equal, and gives you less weight in international affairs. But it’s not a particularly big deal. In fact, all the most successful countries (Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, New Zealand, Singapore) have relatively small populations.

But the 8 million are not a random sample – far from it, in fact.

Because “fighting age” men (those under 60) are prohibited from leaving, around 85% of adults who’ve gone are female. Which means that almost six times more women have left than men. According to the CIA World Factbook, Ukraine’s pre-war sex ratio was substantially female-skewed at 0.86, so you might say it’s not a bad thing that so many women have left. After all, it will even out the gender balance. But that ignores age distributions.

Ukraine’s pre-war sex ratio only departs significantly from unity above age 55. It’s 0.76 in the 55–65 age group, and 0.51 in the 65+ age group. (This is due to large numbers of men dying early from things like alcohol abuse; you see the same pattern in Russia.) So before the war, there were many more older women than older men, but about the same number of young women as young men.

As for Ukraine’s refugees, the UN reports that 72% of adults who’ve gone are women under 60. A further 10% are men under 60. And the remaining 18% are people over 60. In the 18–34 age-group (the one crucial for family formation) over six times more women have left. So while the refugee crisis has slightly evened out the gender balance at older ages, it’s created an imbalance at younger ages: Ukraine now has a deficit of young and middle-aged women.

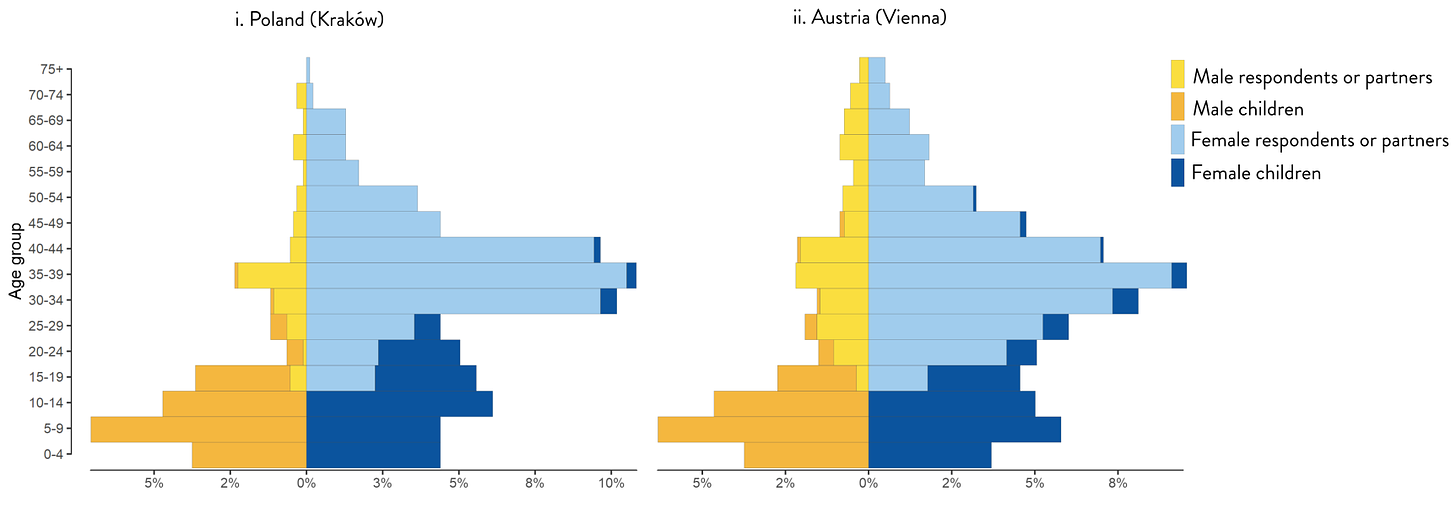

The charts below show the age and gender distribution of two refugee samples taken in Kraków and Vienna. As you can see, young and middle-aged women are substantially overrepresented, while young men are underrepresented.

Ukrainian refugees are unrepresentative not only with respect to gender, but also with respect to education. According to the UN, 76% have a tertiary education – compared to only 30% in the pre-war population. Likewise, the researchers who created the charts above found that 66% of refugees in Kraków, and 83% of those in Vienna, had a tertiary education. So Ukrainian refugees are more than twice as well-educated as the population at large, despite having a similar age structure.

Of course, it’s not surprising that Ukrainian refugees would be positively selected for education. Educated people are more likely to speak a foreign language, more likely to have travelled internationally, and more likely to have friends or contacts in other countries.

Ukrainians refugees are also positively selected for employment. The UN reports that only 4% of them were unemployed at the time of leaving, whereas Ukraine’s pre-war unemployment rate was almost 9%. This comparison underlines the degree of positive selection among those who’ve left, since you might expect that people with a job would be less likely to pick up and go.

“So what?” you might say. “Most of those people will return when the war’s over.”

But will they? So far as modern refugee crises go, this one is more-or-less unique. The country people are fleeing is much poorer and more corrupt than those around it. In fact, Ukraine’s pre-war GDP per capita was the lowest in Europe at $14,150 (and is now lower still, thanks to the war). By comparison, GDP per capita in Austria is $66,680. Even Russia’s GDP per capita is more than double Ukraine’s.

What’s more, the countries hosting Ukrainian refugees have been relatively welcoming. Polls consistently show that Western populations are more accepting of Ukrainian refugees than those from other conflict zones, presumably because they see them as more culturally or ethnically similar. While the Poles fiercely resisted accepting Syrian refugees in 2015, they have opened their borders to more than 1.5 million Ukrainians – more than any other country besides Russia.

So Ukrainian refugees find themselves in countries that are not only richer and better governed than the one they left, but also generally hospitable. This gives them ample reason to stick around once the war is over. And naturally, the longer the war goes on the more likely they are to stay, since they’ll have had more time to integrate into their host societies, and Ukraine itself will be in even worse shape.

“There is little reason to suggest many Ukrainian refugees will return home soon,” argues the journalist John Ruehl in a recent article. Similarly, the researcher Kateryna Odarchenko warns that “at least five million refugees are not expected to return home”. One survey of Ukrainians in Germany found that 37% would like to settle there “permanently or for several years”. And that’s before factoring in social desirability bias (respondents feeling an obligation to say they will go back).

Even if half of those who’ve left eventually go back, that still represents a huge loss for Ukraine.

Talented, hard-working people are the single most important resource for a country’s economic development, and Ukraine is set to lose a lot of them. The number of educated emigrees may even rise, as married men rejoin their families in other countries when the war ends. (Marriage is highly assortative, so the husbands of educated women tend to be just as educated; often more so.)

Alternatively or additionally, the sex ratio among those under 60 may become male-skewed, at least for a time. This would set Ukraine on a path toward greater violence and social instability, as young men compete with one another for access to comparatively scare women, and some are inevitably left without partners. The fact that such competition would occur in an environment replete with deadly weapons is further cause for pessimism.

On top of economic devastation, Ukraine faces a profound demographic crisis: the loss of millions of educated young women (and potentially their husbands too). The scale of this demographic crisis will only worsen the longer the war drags on, which reinforces the case for ending it as soon as possible.

Image: Amudena Rutkowska, Feast of Transfiguration in Spas village, 2017

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

Ending the war "as soon as possible" will only help if Ukraine wins decisively. Minsk III would leave a Damoclean sword hanging over Ukrainian civil society, which would cause even more refugees. A partition along the Dnieper (thankfully unrealistic at this point of time) would permanently displace a large part of the country's population, even if Western Ukraine can improve its standing to Eastern EU levels. (Remember Vietnam?) No one in Eastern Europe trusts Putin's guarantees any more, and it is only reasonable to expect him to repeat a winning formula, so even some Eastern EU countries would lose their best and brightest.

The cynic in me will notice that Western countries like Germany and Britain probably *want* more Eastern EU immigration even if they cannot quite find the words for this desire. But narrowing one's realm of influence (and free movement even) further and further is not a good long-term strategy.

> So Ukrainian refugees are more than twice as well-educated as the population at large, despite having a similar age structure.

This is slightly ironic in light of the fact that surveys also suggest that willingness to fight Russia until the recovery of all territories (pre-22/2/22) tracks education.

Anyhow, not much to disagree with here, it tracks my own analysis. Post-war backflow will be balanced by men reuniting with wives in the EU. Ironically, virtually regardless of what happens militarily, Russia will further improve its demographic preponderance over Ukraine (this may or may not be relevant so far as the future is concerned; depends on the political and security reconfigurations that accompany the war's end). The one thing Ukraine does have have going for it is that any "Malorossiyan" or "pluralist" identity, as opposed to "monist" Ukrainianism, already very enervated prior to the war, will end forever. Whether the frontlines end up, there's just be Russians and Ukrainians to the east and west of them, respectively.