Bryan Caplan is one of the few pro-immigration activists who takes his arguments to their conclusion: open borders. He believes there should be essentially zero restrictions on migration; that more or less anyone should be free to move anywhere. Here’s how he summarised the case for Vox:

What would you think about a law that said that blacks couldn’t get a job without the government’s permission, or women couldn’t get a job without the government’s permission, or gays or Christians or anyone else? So why, exactly, is it that people who are born on the wrong side of the border have to get government permission just to get a job?

While I disagree with Caplan about open borders, I can’t deny that his arguments are coherent. If you believe that national borders are morally arbitrary, then logically you shouldn’t just support letting some migrants in; you should support letting all migrants in. And Caplan does.

As he might argue: nobody seriously disputes that people born in one part of a country should be free to move to another part of that country. So why is it different with national borders?

Caplan, then, is a true pro-immigration activist. He’s actually in favour of immigration. By contrast, there are many out there who claim to be in favour of immigration, but for all intents and purposes are not. They’re simply masquerading as pro-immigration activists.

Whom do I have in mind? In the British context, people who say they’re in favour of immigration insofar as they support the EU Single Market. Or people who say they’re in favour of immigration insofar as they support granting asylum to those arriving in boats on the south coast of England. Basically, people who support current levels of immigration.

But current levels are high; this year saw net migration climb to an all-time record of 504,000. So how can I say that people who support current levels aren’t really in favour of immigration?

Well, 504,000 people might be large by historical standards, but it’s a small percentage of the number who want to migrate.

Over the last decade or so, the polling company Gallup has asked people in most of the world’s countries a simple question: “If you had the opportunity, would you like to move PERMANENTLY to another country?” As of 2018, more than 750 million people said “yes”.

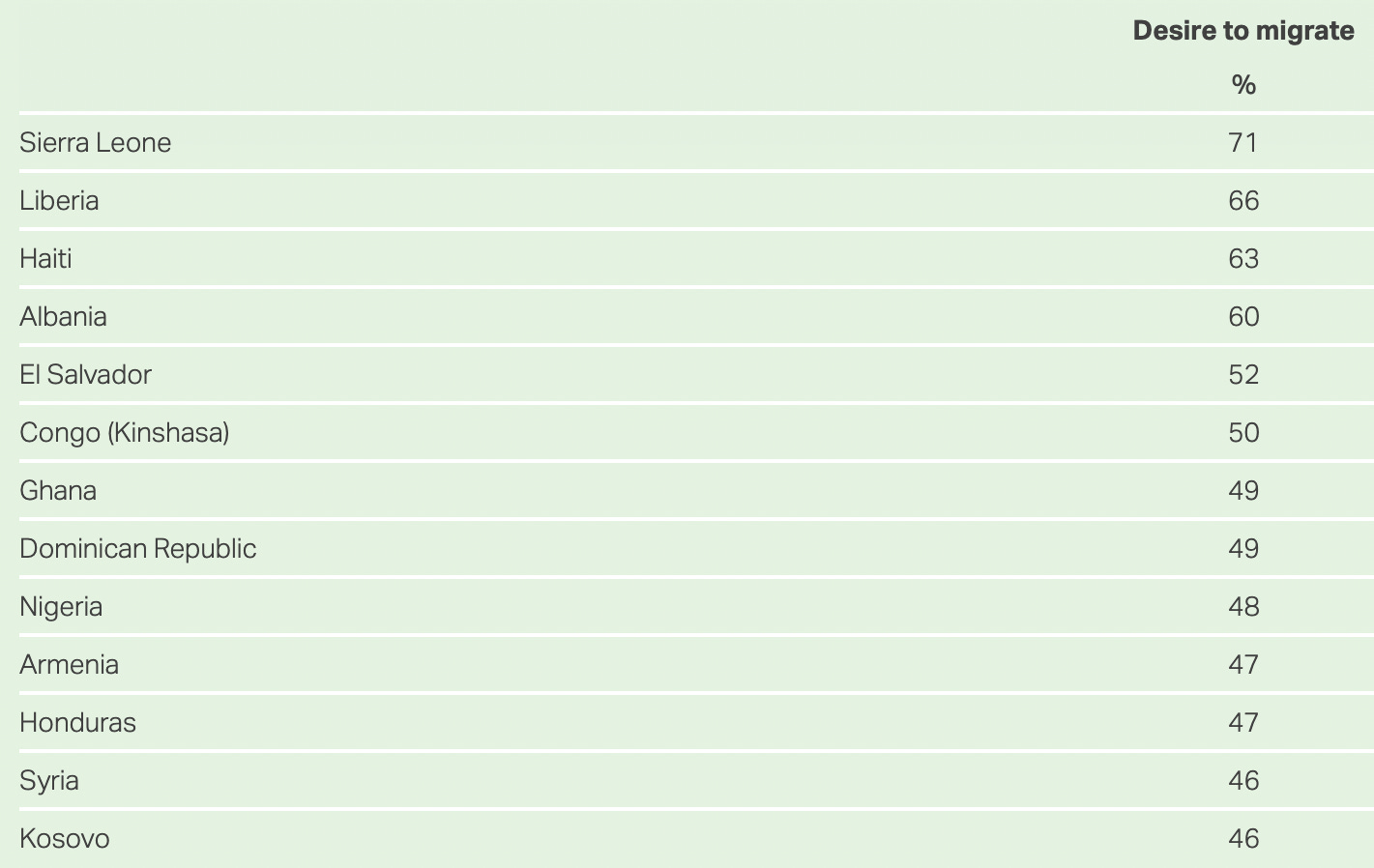

Unsurprisingly, the countries with the highest percentage of people who want to migrate are not places you’d generally like to live; they tend to be poor, corrupt and violent. The top twelve (for which data are available) are shown below:

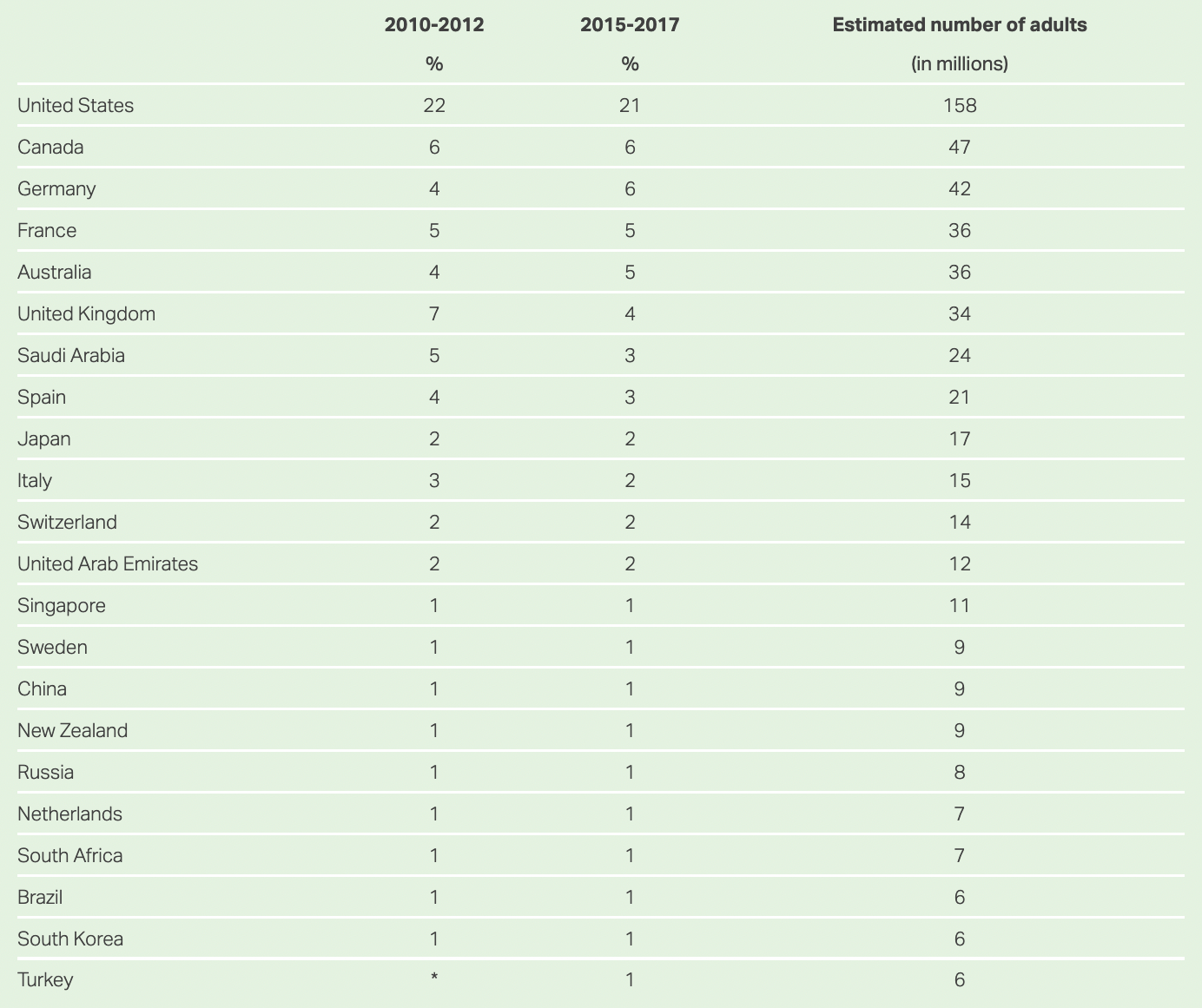

Respondents who answer “yes” are then asked, “To which country would you like to move?”. The most population destination countries, which “have generally been the same for the past 10 years” according to Gallup, are shown below:

The pattern here is obvious: large, rich countries with already-high levels of immigration are the most popular. Based on the percentage of respondents naming each country, and the populations of the countries in which they reside, Gallup has estimated the total number of people who want to migrate to each destination country. (Of course, many would be happy to go to any of the top five or ten, so these figures are lower bounds.)

For the UK, it’s 34 million. This is the number who would move “permanently” to the UK “if they had the opportunity”. 504,000 now doesn’t look so large. In fact, it’s only 1.5% of the total number who want to migrate.

So if you support current levels of immigration, you’re much closer to someone who wants zero (or close to zero) immigration than you are to someone like Caplan. After all, you’re against the vast majority of the immigration he would like to see. So for all intents and purposes, you’re not pro-immigration.

Okay, but is it realistic to imagine that 34 million people would come if Britain opened its borders? Yes. In fact, if the country did so unilaterally, I don’t doubt that many more than 34 million people would come (since they couldn’t go to the US, or France or Germany instead). They might not all arrive in the first year, but the numbers would quickly ramp up once diaspora communities had been established.

If you think this is implausible, consider these two historical examples.

Until 1990, Romania was one-party communist state, with opportunities to leave being severely limited. This changed after the fall of communism, and large numbers of Romanians began moving to Spain, Italy and Germany. When the country became an EU member in 2007, further outmigration took place, including to places like Britain.

By 2020, 18% of Romanians (almost one in five) were living outside the country – mostly in Spain, Italy and Germany. And note: the difference in living standards between Romania and those other European countries isn’t even that big. Measured at purchasing power parity, Romania’s GDP per capita is about 60% of Germany’s (thanks in part to catch-up growth since 1990).

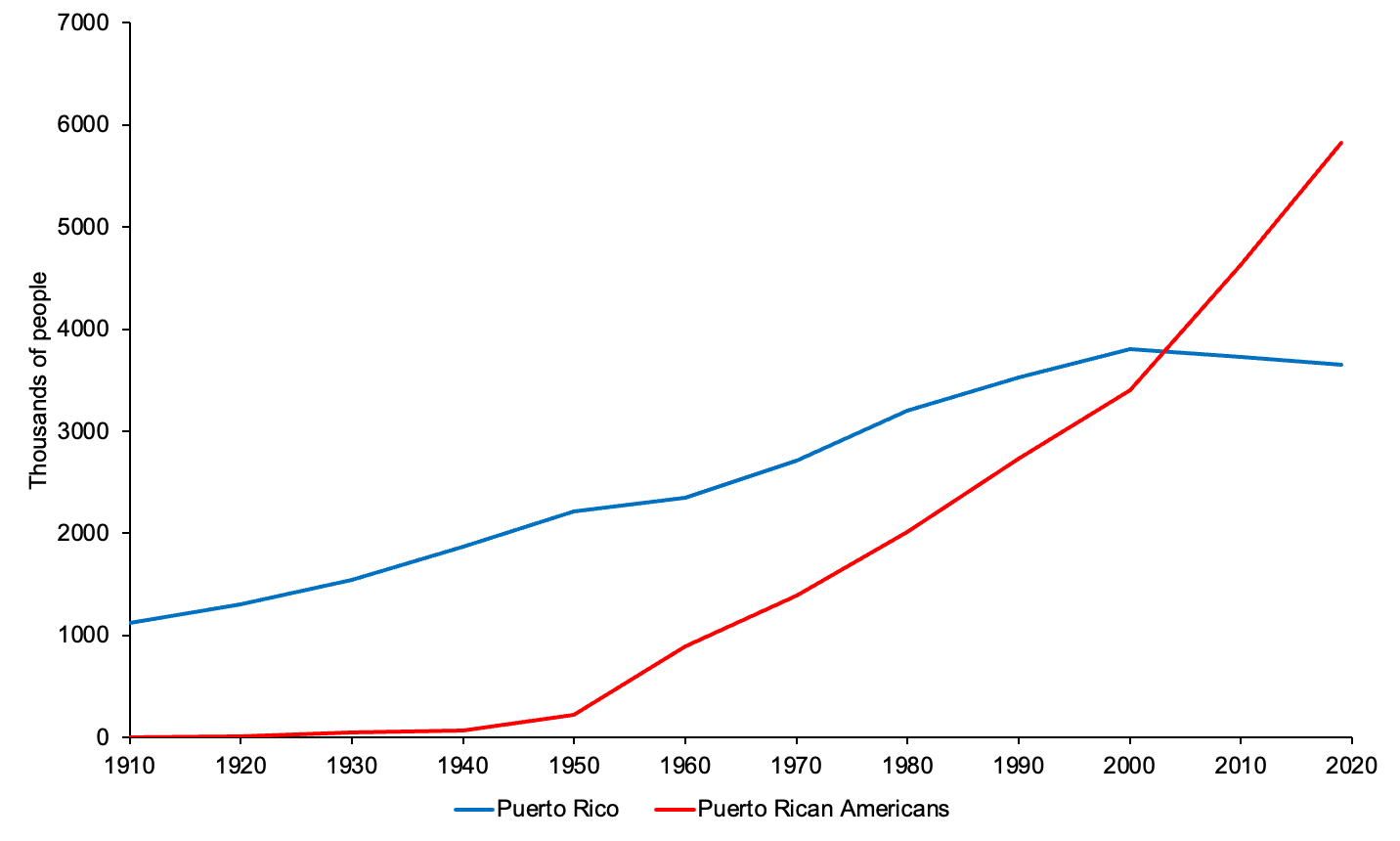

The second example is Puerto Rico, which in 1898 was annexed by the US. Outmigration was initially limited, and unsurprisingly fell during the Great Depression. Yet it picked up after the Second World War. Up to 500,000 Puerto Ricans went to the mainland during the fifties, representing almost a quarter of the territory’s population in 1950.

By 2010, there were more Puerto Ricans on the mainland than there were in Puerto Rico itself. And since 2000, the population of Puerto Rico has actually been falling (it continued rising in earlier decades owing to then-high birth rates). Once again, the difference in living standards between Puerto Rico and the mainland US isn’t that big; the former’s GDP per capita is about half the latter’s.

The examples of Romania and Puerto Rico show that when there are open borders between a relatively poor country a relatively rich country (or countries), substantial outmigration may occur.

Yet these examples may understate how much immigration Britain could expect under open borders today.

The countries with the highest percentage of people who want to migrate have much lower living standards than Romania or Puerto Rico. Those two states have GDP per capitas around $35,000, whereas places like Sierra Leone and Liberia have GDP per capitas less than $2,000. And migrating is less costly than it was in the past. There are more ways to travel and doing so is cheaper. Plus, modern technology means that staying in touch with friends and relatives back home has never been easier.

On the other hand, Romania and Puerto Rico are obviously closer to Western Europe and the US, respectively, than places like Sierra Leone and Libera are to Britain. In fact, the cost of travelling to all the way to Britain by plane might initially be prohibitive for some potential migrants in the poorest countries.

Another reason why 34 million people moving to the UK isn’t implausible is that there are already countries with an even larger foreign-born population. As of 2019, migrants comprised 72% of Kuwait’s population, 79% of Qatar’s population and 88% of the UAE’s population. 34 million, by contrast, would be “only” one third of Britain’s post-migration population.

Many people think the current level of immigration is something given by nature, and you can either be a bad person (like Nigel Farage) who wants it to be lower, or a good person (like them) who wants it to stay the same. What they don’t seem to appreciate is that we exclude the vast majority of people who want to migrate.

From Bryan Caplan’s point of view, those who support current immigration levels are deeply restrictionist. Whether they say so or not, they still want to “shut the door” on millions of badly-off people who happened to be born on the wrong side of a national border.

Here’s the question I’d like to see answered by someone who considers themself to be in favour of immigration but who’s against open borders. By what principle do you justify admitting some of the people who want to migrate, while excluding the vast majority? (Aside from national self-interest, which would in any case rule out much contemporary immigration.)

To me, this looks less like a “pro-immigration” position and more like an “anti-Nigel Farage” position.

Image: Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The People's Census at Bethlehem, 1566

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

Caplan is a professed anarchist but he assumes incorrectly that if the Western governments control the roads, streets, parks, etc. in their respective territories, then these spaces are somehow owned by the world because these spaces are not directly owned by Individuals. However, as the libertarian philosopher Jan Lester explains in the linked paper below, all property not directly owned by the natives is held in trust for them by their governments. Therefore, they can choose via the ballot box to bar mass immigration because the roads, etc. are essentially their private property (or would be under a fully-privatized, libertarian anarchy). https://philpapers.org/rec/LESIAL

All of the same particular ethnic group makes the same argument; this is arbitrarily defined and valued, there is an equivalent to this that we accept, thus logically there should be no reason to not permit X. This applies to everything from politics, psychology to economics. I’d argue nothing is arbitrarily defined or valued, and even if something is arbitrarily defined, it does not need to be precisely defined to not do Z because we behave in approximate ways (heuristically) that are advantageous to our existence. The main premise is, we should not classify, categorize or discriminate against anything, which is logically an absurd presupposition. No system in reality works by being indefinitely open, there must be some boundary in which feedback loops occur, for there to be some construction of order; whether it be a nation, a group or a collection of cells. You don’t just let foreign material through your body passively because it decreases the stability of the system (I.e homeostasis), the same argument can made against the fluxes and flows of individuals. Distributing people and allocating them efficiently by their innate potentials is necessary. Otherwise we just get a free dispersion from high energy states to low (i.e. people with the abilities, aptitudes, mindsets and values that can maintain, sustain and develop civilization to those that can’t). The latter are categorically larger than the former. Thus his views are only applicable if every being was interchangeable in favoured attributes, then it would be immoral to disallow any beings from being imported. Even if such people could be “educated” and skillfully trained to the same level, it costs resources. Thus one needs to ask why it is necessary to expend resources to develop other peoples existences when there are an infinite supply of potential beings that come into existence that don’t like to live amongst their shared communities and won’t expend energy to better their own geographically similar areas. Also are nations really arbitrary or geographic borders? Landmasses are unlikely to be arbitrary as the people that historically originate from various locations descend from differently imputed values and skills, some such as “working on a mountain range” are not directly transferable with attributes such as “being able to live comfortably in high attitudes”. Even assuming these beings are interchangeable in qualities and landmasses are just arbitrarily defined, why would someone that be economically selfish want competition with diminished public utilities, housing, availability of opportunities or any other thing? Furthermore, shouldn’t the very best of such emigrants be developing their areas first. Most people that say they are pro have an agenda to push (minority dynamics) or do not live within the large boundaries of settled emigrants and thus do not feel their effects from second generation and later progeny, else their attitudes would change quickly if their community consisted purely of “economic migrants” from poor, desolate and impoverished areas (whom are neither the best nor brightest) relative to the indigenous native population.