NOTE: I now write for Aporia Magazine. Please sign up there!

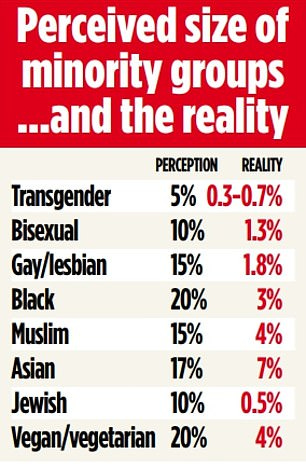

A recent headline in the Daily Mail states: ‘British public hugely overestimates the size of minority groups, including trans and gay people and vegans, study shows’. The article was based on a YouGov poll which asked people to guess what percentage of the population belongs to different minority groups. It found that the average guess was substantially greater than the true percentage in every single case. For example, the public said that 15% of the population is gay, whereas the true figure is much lower (see below).

The poll was commissioned by the Common Sense Campaign, who took the results as evidence that efforts to promote “diversity” have skewed public perceptions. In other words, people see so many black people on TV they assume black people comprise a much greater share of the population than they really do. As one Tory MP noted, “This distorted impression created by much of the broadcast and online media is so out of tune with the facts as to befuddle people about the true character of Britain.”

Interestingly, similar findings from a few years ago were taken as evidence that right-wing commentary around immigration had skewed public perceptions. In the 2013 Transatlantic Trends survey, the public guessed that 31% of the population are immigrants, whereas the true figure at the time was only 12%. As the head of the Migrants Right’s Network stated, “It is unsurprising that many of us think 31 per cent of the population are migrants, given the volume of hostile public debate about immigration and its impacts”.

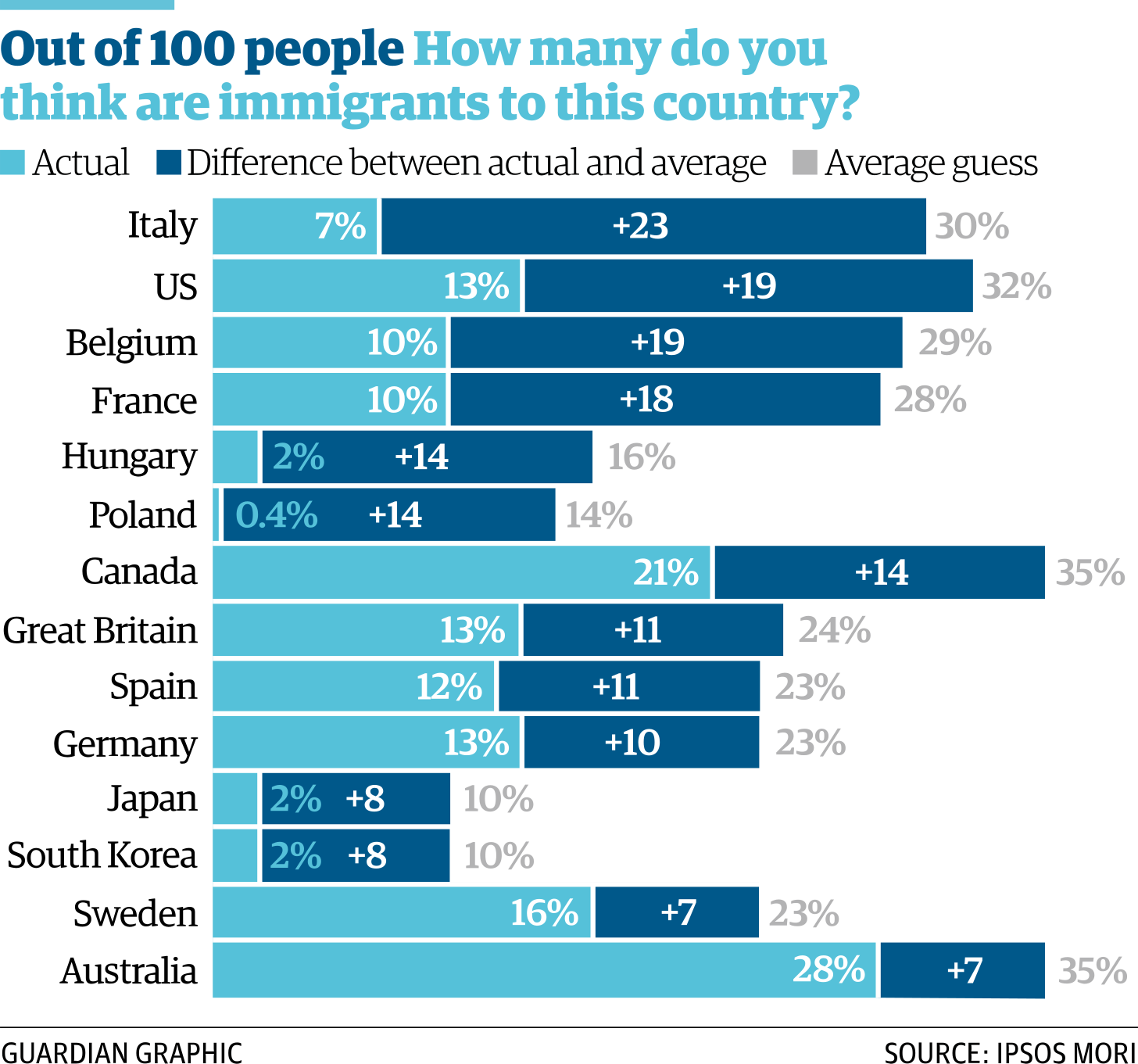

Likewise, in a 2014 survey by Ipsos MORI, the public guessed that 24% of the population are immigrants, whereas the true figure was only 13% (see below). This finding was written up by two Guardian journalists, who said that “it is one thing for public opinion to be shaped by the perception of issues and another when politicians choose to make promises and write policies to feed and satisfy misconceptions.” They referred to a prominent Conservative politician who’d claimed that British towns were being “swamped” by immigrants.

If both left and right think the other side is fuelling misperceptions about the make up of the population, where does the truth lie? The truth is that both sides are probably wrong. Neither efforts to promote “diversity” nor right-wing commentary around immigration can account for skewed public perceptions. (Although these things may have effects, they’re unlikely to be large.) So what does account for skewed public perceptions?

The answer can be found in a paper by David Landy and colleagues. Based on prior research, these authors hypothesised that we rely on Bayesian reasoning (consciously or otherwise) when we’re asked to estimate a percentage. We begin with a value from our own experience, and then adjust it upwards or downwards toward 50% (the prior probability). If we’re asked about something that seems “common”, we begin above 50% and then adjust downwards. If we’re asked about something that seems “rare”, we begin below 50% and then adjust upwards. For something we have absolutely no clue about, we just stick with 50%. Landy and colleagues refer to the process of adjustment as “uncertainty-based rescaling”. Here’s how they describe it:

Say that you are asked about the proportion of Americans who are Cambodian Americans. Sampling from your experience, you might expect this proportion to be quite low … On the other hand, you have lots of experience with demographic subgroups in general. Most such groups are much larger than the Cambodian-American population, and only very few are smaller … Thus, on the basis of your experience with the distribution of demographic proportions, you could reasonably infer that your sample of Cambodian people is unrepresentative … Even if your memory sample of Cambodian Americans was actually unbiased … then a rational reasoning process would push you to systematically overestimate the proportion.

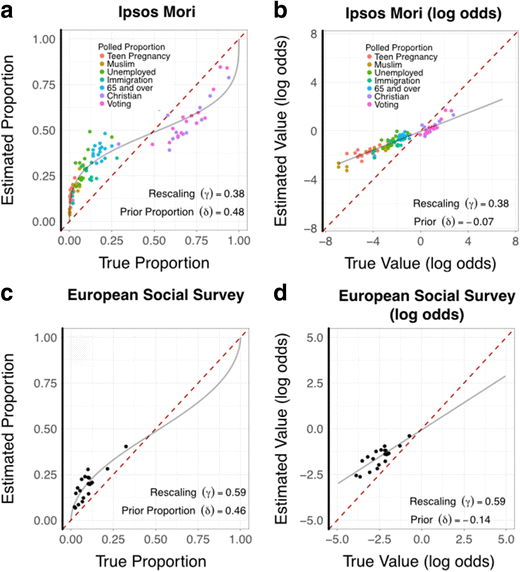

This means that in situations of uncertainty (such as when we’re asked to estimate demographic proportions), there will be systematic overestimation of small values and systematic underestimation of large values – regardless of what is being estimated. And this is exactly what we see. Landy and colleagues analysed data from two large surveys, and found that proportions greater than 50% were almost always underestimated, whereas proportions less than 50% were almost always overestimated. They also found that, for percentages close to 50%, respondents were usually about right (see below).

After accounting for uncertainty-based rescaling, the authors found little evidence of issue-specific biases. For example, there was no obvious tendency for people to overestimate the proportion of immigrants, as compared to other quantities of similar magnitude. As Landy and colleagues put it, “error that has been interpreted previously as topic-specific “ignorance” is actually predicted systematically by a simple, issue-agnostic psychophysical model of proportion estimation under uncertainty.” Their findings suggest that while people are ignorant about the make up of the population, they’re not substantially more ignorant about minority groups.

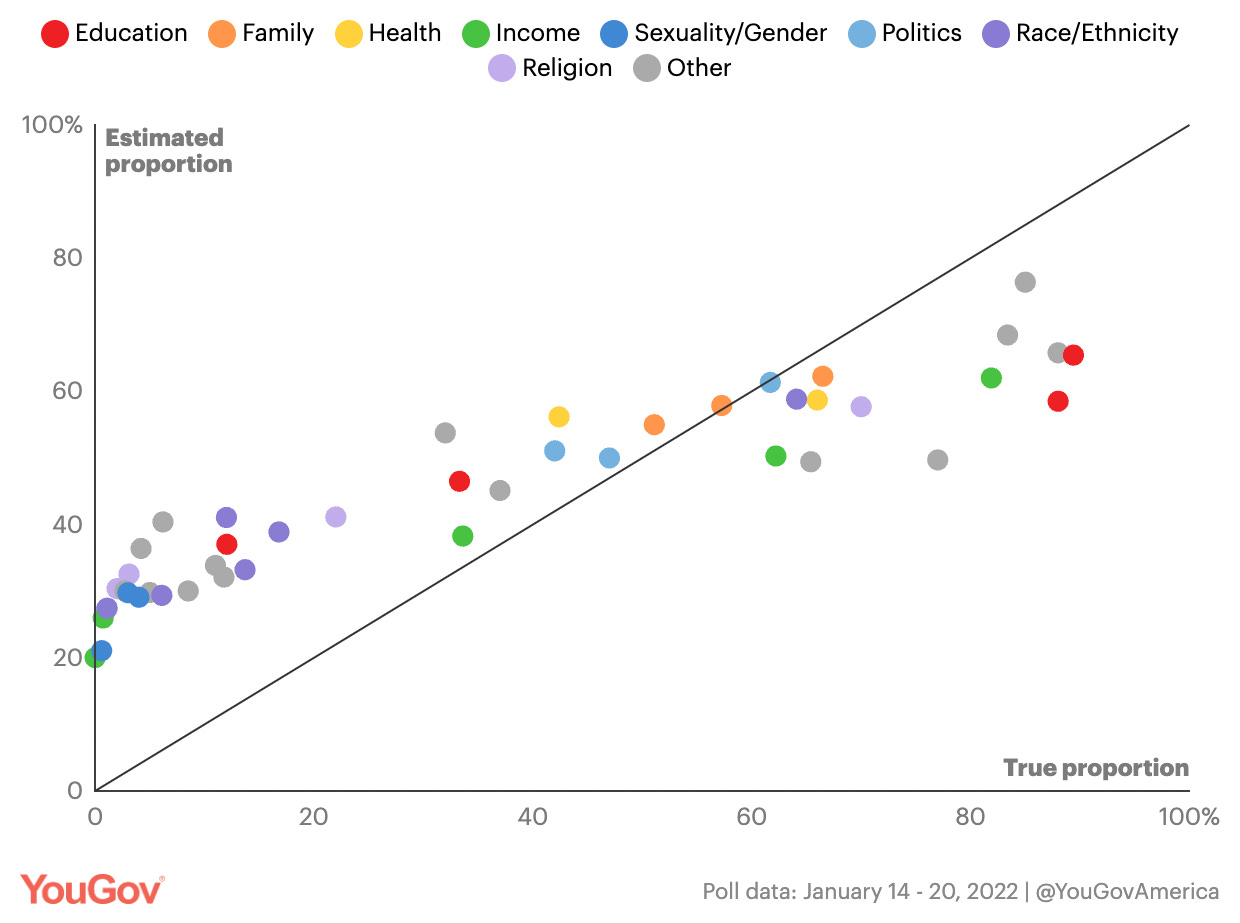

In the write-up for another recent poll, YouGov actually referred to Landy and colleagues’ paper. Interestingly, that poll sampled Americans, and found even more-skewed perceptions than in the other two surveys. As the chart below indicates, Americans’ average guesses were heavily concentrated between 40 and 60% regardless of the quantity being estimated. (In the most extreme case, Americans guessed that 40% of the population are military veterans, whereas the true figure is only 6%.) Compare this pattern to the upper-left panel in the chart above – which shows a clear S-shaped curve.

Another example where uncertainty-based rescaling popped up was 2019’s “Perception Gap” study. Large samples of Democrats and Republicans were asked to estimate the proportion of their political opponents who hold various beliefs. For example, Democrats were asked what proportion of Republicans believe “racism still exists in America”, while Republicans were asked what proportion of Democrats believe “most police are bad people”.

Sizeable disparities were observed between actual and estimated proportions, which was taken as evidence that “Americans have a deeply distorted understanding of each other”. However, if you look at both sets of results, they suggest that most people were just guessing around 50%. In other words, it wasn’t that partisans had systematically wrong beliefs about their opponents; it was that they were clueless. Which is why their answers exhibit a large degree of uncertainty-based rescaling. As a far as I’m aware, this wasn’t mentioned in any of the popular write ups.

While people have a decent sense of the rank-order of different quantities – as the literature on stereotype accuracy shows – they’re not very good at guessing the actual values. And when it comes to percentages, they have a tendency to “rescale” those values upwards or downwards toward 50%. Consequently, surveys can reveal dramatic disparities between actual and estimated proportions in the absence of any issue-specific biases. While efforts to promote “diversity” or right-wing commentary around immigration may play a role, the effects are going to much smaller than is commonly assumed.

Image: Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The People's Census at Bethlehem, 1566

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

Interesting stuff as usual, Noel. Interesting to note how much these misestimates are encouraged by other minorities. For example, look to the number of minority issues covered on the BBC website!

I think there's also a philosophy that if enough minorities a lumped together, they become a majority. This is now becoming common in, eg, "17 activist groups believe.....", even if some of them are just two men and a dog! P

..”error that has been interpreted previously as topic-specific “ignorance” is actually predicted systematically by a simple, issue-agnostic psychophysical model of proportion estimation under uncertainty”.

Pithy that😬. Great piece Noah. One of the problems of perception abd understanding for everyone (even trained social scientists) is this insistence on indecipherable, arcane language by researchers. Its as though every word is designed to obfuscate. Not the fault of Landy et al more “systematic uncertainty of journal acceptance of non quasi hyperbolic qualifiers in abstract title!