Vaccinating the elderly saved lives

This article first appeared in the Daily Sceptic.

The Daily Sceptic’s purpose is to question the conventional wisdom – something that’s more important than ever in the era of NPC-slogans like ‘Follow the Science’. But in this article, I’d like to uphold one piece of conventional wisdom: that vaccinating the elderly saved lives.

Now, this is far from a full-throated endorsement of the conventional wisdom on Covid vaccines. For instance, the conventional wisdom has it (or at least had it) that everyone needs to get vaccinated – regardless of age, physical health or prior Covid status. Yet there’s a decent case to be made against vaccination for young healthy people and/or those who’ve already had the virus.

Likewise, the conventional wisdom insists not only that everyone should get vaccinated, but that everyone must get vaccinated. Which is why until quite recently, you couldn’t get on an airplane without being vaccinated. I was strongly against the vaccine mandates, and my stance certainly hasn’t changed.

For those keeping score, I’ve always said the vaccines were a way of achieving focussed protection against Covid. And I continue to believe that vaccination was the right choice for most elderly people and others in high-risk groups.

At this point, a purveyor of the conventional wisdom might claim: there’s already overwhelming evidence of vaccine effectiveness against death, so what more needs to be said?

Yet as sceptics are well aware, there are problems with the evidence for vaccine effectiveness against death. Simply comparing Covid death rates among vaccinated and unvaccinated people, as purveyor of the conventional wisdom are fond of doing, isn’t satisfactory. (Note that the original RCTs were “not designed or powered to assess whether the vaccines prevented deaths”.)

First, there’s immortal time bias: because vaccinated people are often classified as ‘unvaccinated’ until two weeks after vaccination, deaths that occur during this window are not counted or wrongly assigned to the unvaccinated group, artificially inflating vaccine effectiveness.

Relatedly, there’s the ‘healthy vaccinee’ effect. Unvaccinated people are more likely to die of causes other than Covid, implying that they tend to be less healthy and/or less risk-averse than vaccinated people. Failing to account for this again leads to overestimation of vaccine effectiveness.

There’s also the phenomenon of waning. Some studies suggest that vaccine effectiveness against death wanes over time, just like vaccine effectiveness against infection. So even if the vaccines do protect against death, such protection may be relatively short-lived.

Finally, there’s the fact that some ‘Zero Covid’ countries like South Korea saw large spikes in excess mortality even after the vast majority of elderly people had been vaccinated. These data are hard to reconcile with commonly heard claims of 90% vaccine effectiveness against death.

One way to get round these problems is by using aggregate-level data: compare places where more elderly people got vaccinated to those where fewer did, and see whether excess mortality was lower. Any resulting correlation can’t be explained by immortal time bias or the ‘healthy vaccinee’ effect since those don’t apply at the aggregate-level.

And the use of excess mortality, rather than the official Covid death rate, obviates the problem of correctly classifying Covid deaths.

To see whether excess mortality was indeed lower in places where more elderly people got vaccinated, I obtained data on countries in the European Economic Area – the 27 EU member states, plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. These countries are culturally and economically similar, so the sample is appropriate for testing claims about vaccine effectiveness.

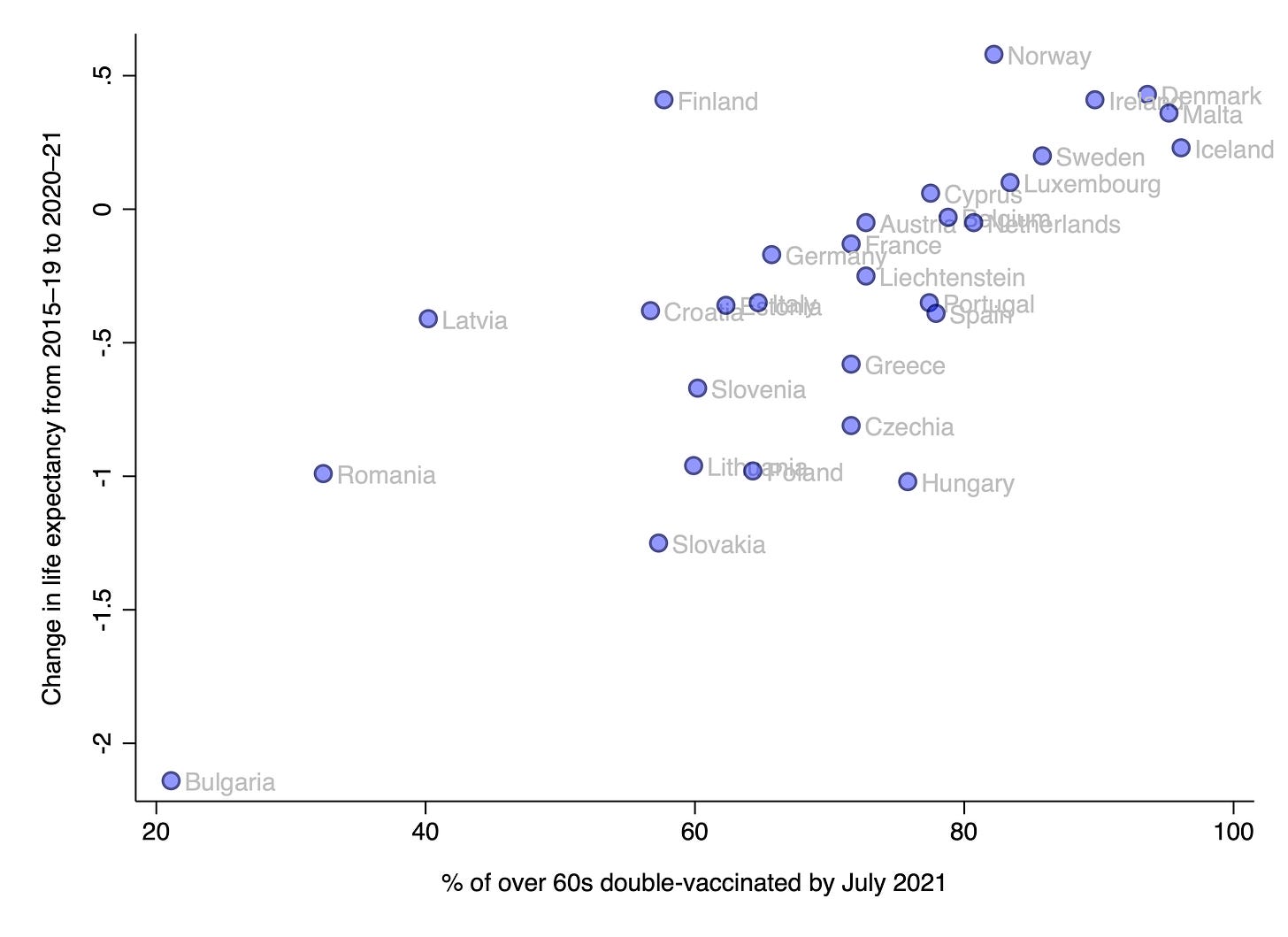

Data on the percentage of over 60s double-vaccinated by July of 2021 (the halfway point of that year) were taken from the European CDC. Data on life expectancy were taken from Our World in Data.

To calculate change in life expectancy, I subtracted average life expectancy in 2020 and 2021 from the average in 2015-2019. This indicates how much lower life expectancy was in the first two years of the pandemic than in the previous five.

You might say that 2020 should be excluded from the analysis as the vaccines only became available at the end of that year. However, the level of mortality in 2021 will be lower, all else being equal, for countries that had greater mortality in 2020. So it makes sense to take both years’ data into account. In any case, results are basically the same if 2020 is excluded.

The chart below plots change in life expectancy against elderly vaccination. The relationship is very strong and positive: in the most-vaccinated countries life expectancy stayed the same or even increased, whereas in the least-vaccinated countries (notably Bulgaria) it fell by 1–2 years.

Of course, correlation doesn’t equal causation. Just because elderly vaccination is correlated with change in life expectancy, doesn’t mean the former caused the latter. So what other factors might explain the association?

Two obvious possibilities are: obesity and healthcare spending. Maybe it proved more deadly in places where more people were obese? Or maybe Covid proved more deadly in places where the healthcare system was worse at treating people?

When I tried controlling for these factors in a simple multivariate model, healthcare spending was more strongly associated with change in life expectancy than was elderly vaccination. On the other hand, obesity was not associated with change in life expectancy.

One could interpret these findings as showing that healthcare spending is the true causal variable, and elderly vaccination barely matters. However, I suspect that because the sample comprises only 30 countries, it is not possible to disentangle the effects of elderly vaccination and healthcare spending. (Perhaps some third factor causes both low elderly vaccination and less healthcare spending.)

To get a slightly larger sample, I turned to U.S. states – which provide another useful setting for testing claims about vaccine effectiveness.

Data on % of over 65s double-vaccinated by July 2021 were taken from the CDC, as were data on all-cause deaths among over 65s. To calculate excess mortality, I subtracted average deaths in 2020–21 from the average in 2015–2019, and then divided the answer by the average in 2015–2019 (and multiplied by 100).

The chart below plots excess mortality against elderly vaccination. As before, the relationship is very strong: in the most-vaccinated states excess mortality was less than 15%, whereas in the least-vaccinated states it was more than 20%.

When I tried controlling for healthcare spending and obesity in a multivariate model, neither factor was strongly associated with excess mortality. By contrast, elderly vaccination was a consistently strong predictor.

In other words: in the larger US sample, the correlation between elderly vaccination and excess mortality can’t be explained by either obesity or healthcare spending. Perhaps there’s another variable that can explain the association, but it’s hard to imagine what it might be. (Neither age or racial demographics is going to work.)

As mentioned above, none of the results change substantially when excluding the 2020 mortality data. In fact, elderly vaccination is a more robust predictor in the European sample.

To sum up, elderly vaccination is strongly correlated with excess mortality in both Europe and America. The association is robust to controlling for obesity and healthcare spending in the American sample, though it diminishes substantially in the European sample. The latter result may be due to the small sample size, making it hard to disentangle the effects of correlated predictors.

One issue my analysis doesn’t really address is waning. Perhaps the vaccines don’t protect against death after the first year, so if I’d included the 2022 mortality data, I would have found no correlation or a much-reduced one? While life expectancy data isn’t yet available, there’s little evidence that the most-vaccinated European countries saw outsize excess mortality last year.

Iceland is the only one that saw a major spike in excess mortality (though in recent weeks excess mortality has been negative). So while comparisons based on only 2020–21 data may somewhat overstate the association between elderly vaccination and excess mortality, it’s unlikely to be dramatically different when including the 2022 data.

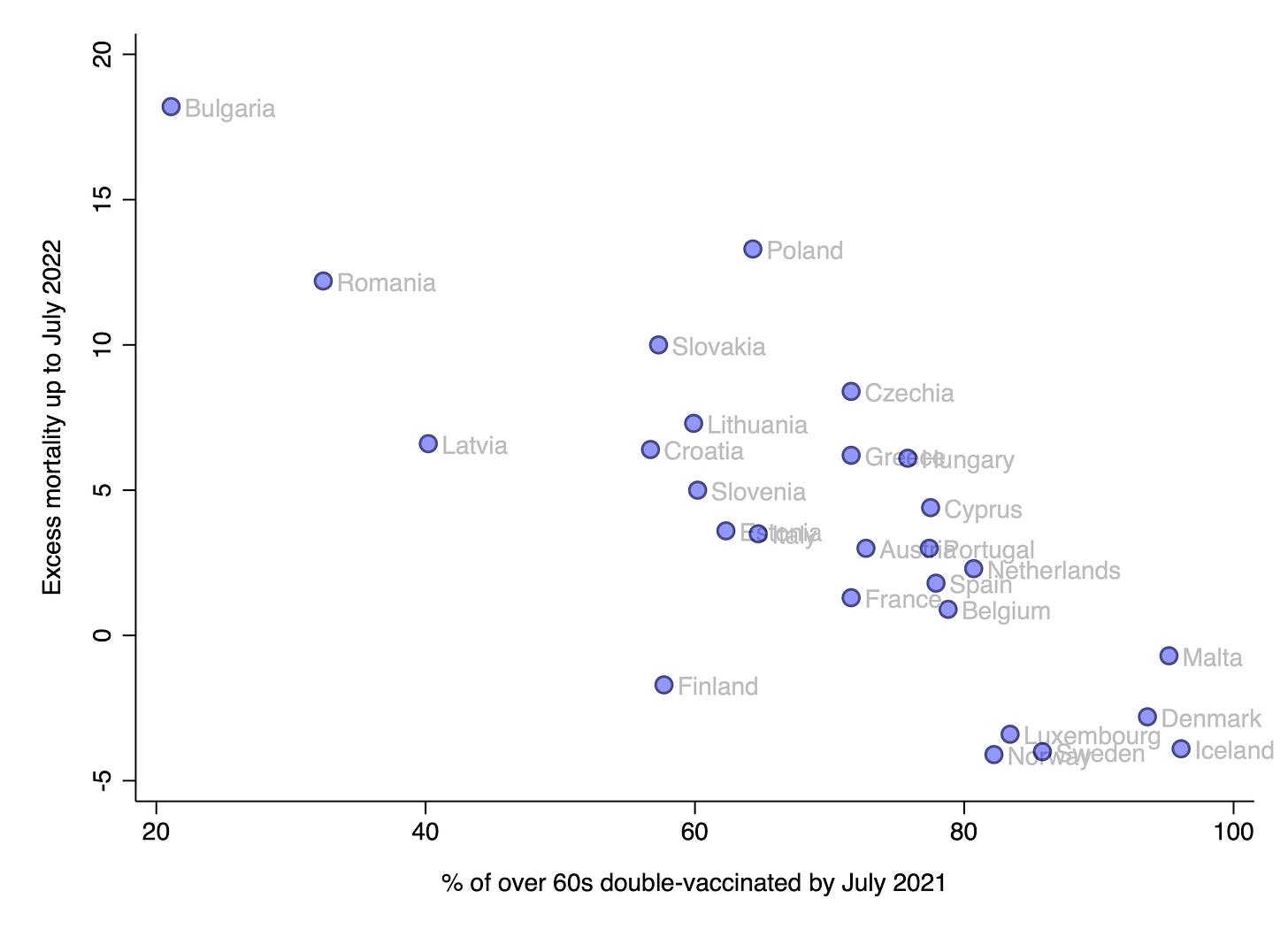

As another check, I obtained the ONS’s latest estimates of age-adjusted excess mortality, which encompass the period from January 2020 to July 2022. The chart below plots these estimates against elderly vaccination for 27 European countries. (They were not available for Germany, Ireland or Liechtenstein.)

The relationship is just as strong as before, indicating that any effect of waning during the first half of 2022 was minimal.

In any case, even if vaccine effectiveness against death wanes all the way to zero after several years, getting vaccinated would still have been the right choice for most elderly people, since two or more years represents a non-trivial increase in one’s lifespan.

The evidence suggests that vaccinating the elderly saved lives. Unlike lockdowns and mask mandates – which had little discernible impact while imposing huge costs on society – elderly vaccination appears to have made a tangible difference. (There is no correlation between lockdowns and excess mortality across European countries or U.S. states.)

Focussed protection culminating in voluntary vaccination of high-risk groups was the right strategy all along – just as the Great Barrington authors argued.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.