The story of the Luddites is well known.

They were a group of skilled textile workers in 19th century England, who went around smashing up new machinery because they feared (correctly) that it would render them obsolete. Before the invention of the power loom, textile workers had to spend years years honing their skills; afterward, unskilled workers and even children could be put to work making textiles. “Luddite” has since come to mean “someone who opposes technological change”.

With the development of large language models like ChatGPT, will we soon have an “intellectual power loom” – a machine that renders intellectuals obsolete? It looks increasingly likely.

Note that by “intellectuals”, I don’t just mean “academics”. I mean anyone who does any kind of vaguely intellectual work. So that includes journalists, scientists, writers, researchers, lawyers, engineers, programmers, analysts, designers, film-makers and architects.

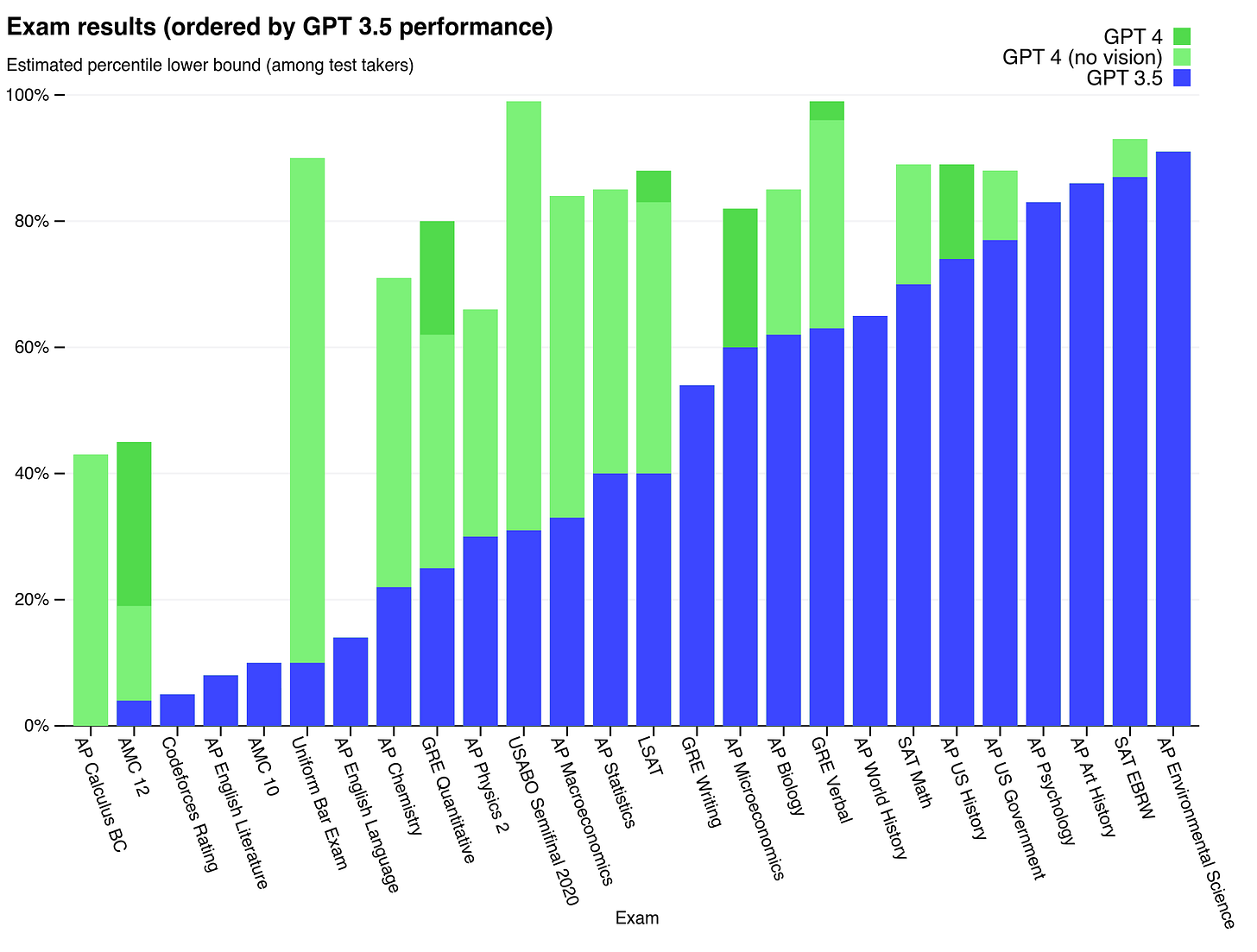

The current version of ChatGPT is obviously not an intellectual power loom. But what’s alarming is that it doesn’t seem too far off. Rather than being smarter than the very smartest humans, it is “merely” smarter than most undergraduates. And since the technology appears to be progressing rapidly, the possibility that some future version will be smarter than the very smartest humans is not at all inconceivable.

If you want a brief report written on a particular subject, you’re better off going to a human specialist than you are using ChatGPT. However, you’re better off using ChatGPT than you are going to most humans. For many intellectual tasks, the current rank order of performance is: human specialist; ChatGPT; most humans. It’s possible that within a decade or two, it will be: ChatGPT; human specialist; most humans.

Imagine you could input the prompt “analyse these data, and write a paper arguing such-and-such”, and the output was better than what a tenured Harvard professor could produce. There’d no longer be much need for academics. Imagine you could input the prompt “review these documents, and draft a contract outlining such-and-such”, and the output was better than what a partner at Clifford Chance could produce. There’d no longer be much need for lawyers. You get the idea.

To be clear, I’m not talking about the scenario that terrifies Eliezer Yudkowsky: an “artificial general intelligence” coming into existence and proceeding to destroy humanity. I’m talking about something much more mundane: the development of an AI that is to human specialists as they are to the current version of ChatGPT – an intellectual power loom.

In this scenario, the AI would become exceptionally smart, but wouldn’t figure out how to make itself even smarter and thereby trigger the “singularity”. It would just be a world in which everyone had John Von Neumann as their personal assistant.

Now, Von Neumann (and other geniuses) have already existed, so what’s the big deal? Well, Von Neumann faced certain limitations. He could only work on one thing at a time. Although he was a brilliant scientist and connoisseur of many fields, he wasn’t necessarily a literary genius of the same calibre as Shakespeare. An intellectual power loom would be the equivalent of Von Neumann, Shakespeare and a dozen other geniuses all rolled into one. And rather than taking weeks or months to get things done, it would do them in a matter of minutes.

In this world, there’d be only one academic journal: Intellectual Power Loom Review. Because no one would write academic papers as well as the AI. There’d be only one film studio: Intellectual Power Loom Pictures. Because no one would make films as well as the AI. And so on down the line. Even on Twitter, the only accounts worth following would be IPL accounts. Because no one would say anything as funny or interesting as the AI.

Given the AI’s intelligence, the economy would presumably be far more productive. Rather than growing at 2% a year, it might grow at 2% a month. As a result, everyone would enjoy a high standard of living. But crucially, all intellectual production would be handled by the AI. After a while, it would probably invent robots capable of doing every other useful task (building, farming, cleaning etc.) At that point, we’d just play video games all day.

Would this be a desirable world to live in? I suspect that many would say yes.

Most people aren’t particularly interested in intellectual production. Which makes sense, since nearly all of it gets done by those in the top 5 or 10% of IQ. Many people see their job as a means to the end of spending time with their families, practicing their hobbies and enjoying creature comforts. To them, it makes little difference whether academic papers are written by fellow humans or by artificial intelligence.

Yet for a minority of people, contributing to the advancement of civilisation is a large part of what gives life meaning.

Of course, there’d be nothing to stop them from writing papers, or producing films, or crafting tweets, in a post-intellectual power loom world. But it would all be equivalent to children drawing stick figures for their parents. Moreover, they’d be aware of that.

Initially, the AI would complement the skills of the very smartest humans. But as it got smarter, things would start to change. Scientists would notice that no one was reading their work; film-makers would discover that no one was watching their films; once-popular Twitter accounts would find they’d lost all their engagement. Prize-winning authors would become the equivalent of OnlyFans creators making $100 per month. In terms of intellectual production, it would be winner-take-all, with the single AI winning everything.

Several thousand years after the dawn of civilisation, humans would have nothing left to contribute. We’d just consume: read; do gardening; play video-games.

The emergence of the intellectual power loom would be fundamentally different from the invention of the original power loom, which is what spurred Luddism in 19th century England. The Luddites opposed the power loom because it deprived them of their livelihoods; they could no longer earn a decent living. The intellectual power loom is threatening not primarily because it would put people out of work, but rather because it would deprive them of meaning – the meaning gained through intellectual discovery and endeavour.

In a post-intellectual power loom world, you could still gain satisfaction from solving crossword puzzles, or reading up on physics, but never from making an intellectual contribution of your own.

Creative, hard-working types are often the most sanguine about new technology; a “Luddite” is the last things they’d want to be. Yet it’s precisely these people who’d lose most from the intellectual power loom’s emergence.

Personally, I think anyone who suggests that nothing would be lost is kidding themselves. But then I’ve always thought it would have been fun to be born during the Scientific Revolution – before all the low-hanging fruit had been picked and there was still so much left to discover.

Which is not to say that a post-intellectual power loom world would be intolerable.

There’d be more to learn, and vastly more to consume. And after the pre-intellectual power loom generations had died out, humans wouldn’t even know what it was like to make intellectual contributions. Perhaps we’d eventually merge with the AI. Perhaps it would invent an experience machine that allowed us to hallucinate any source of meaning we wanted. Or perhaps it would develop drugs or genetic engineering that allowed us to change our very preferences.

At least one thing seems clear. If the intellectual power loom does emerge, smashing up a few mainframes probably isn’t going to stop it.

Image: The Tet from the movie Oblivion, 2013

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

This is the main thing that is motivating me to aggressively prioritize and accelerate across all areas of my life. "Ideacels" are safe for now - if anything, GPT for now helps them be much more productive - but the flip side is that the clock is ticking and we might not have much time any longer to put down on the record any interesting ideas or concepts we have before this too becomes swept away by superintelligent AIs and lose the capability to make any further original contributions to the noosphere. The default guess would be a decade but it could be far sooner and even 2026 which I whimsically suggested in my AI takeover story WAGMI https://akarlin.com/wagmi/ no longer seems entirely fantastical now.

My strong recommendation to writers, thinkers, content creators, etc. is to go forwards with anything you believe in strongly now, instead of dallying any longer. The gap between the smartest humans and the dullest humans is fairly minor. This window, regardless of how it ends, is very unlikely to last long.

https://twitter.com/powerfultakes/status/1599545967052673024

I tend to think that if AI gets that good (and doesn’t hit an unseen wall like we’ve seen with, say, self-driving cars recently), then it shouldn’t be *that* long before we successfully request from it a gene therapy that shifts the human IQ distribution to the right by 30 points, which might then make room for some human specialists again.