Should we take down all the statues?

Statue-toppling is something I’ve written about several times over the past year, so I was interested to read a new essay on the subject by Guardian columnist Gary Younge. Before getting to Younge’s essay, however, let’s briefly review recent developments in Britain and the United States.

Dozens of Confederate monuments were removed following the Charleston church shooting in 2015. And dozens more were removed following 2017’s the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. Yet despite these removals, the vast majority of Confederate monuments were still standing in 2018. Many left-wing commentators, and some right-wing commentators, supported the removal of Confederate monuments on the grounds that the individuals depicted are not worthy of commemoration (since their cause was ignoble), and most of the monuments were put up long after the Civil War (mostly in the 1900s and 1910s – around the time that Jim Crow laws were enacted) and hence were not of real historical interest.

In 2015, the Rhodes Must Fall movement – which had begun in March at the University of Cape Town in South Africa – reached Oriel College, Oxford. Protestors demanded the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes on the grounds that he was an ardent British imperialist and “architect of Apartheid”, who made various disparaging comments about Africans. However, the College decided not to remove the statue, apparently because wealthy alumni had threatened to withhold their donations if it did so. Some left-wing commentators supported the removal of Rhodes’ statue, but most right-wing commentators opposed it.

One obvious objection to removing Confederate monuments or statues of Cecil Rhodes is that the same arguments could be made for taking down huge numbers of other statues. (As it turns out, most historical figures didn’t subscribe to the values of 21st century Western liberals.) This objection was even raised by President Trump, when he criticised the removal of Robert E. Lee’s statue in 2017. Trump stated:

So this week it's Robert E. Lee. I noticed that Stonewall Jackson's coming down. I wonder, is it George Washington next week? And is it Thomas Jefferson the week after? … George Washington was a slave-owner … So, will George Washington now lose his status? Are we going to take down … statues to George Washington?

Trump’s remarks now look rather prescient, given that both Jefferson and Washington were defenestrated in last summer’s protests. In fact, over 200 statues have been either removed or designated for removal since the death of George Floyd – and that’s just the United States. What’s more, the list of toppled statues includes not only Founding Fathers like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, but also men like Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Ulysses S. Grant, Francis Scott Key, Juan de Oñate, Diego de Vargas and Christopher Columbus.

As far as I can tell, fewer left-wing pundits were on board with the defenestration of the figures listed above. After all, Jefferson and Washington are kind of important, and Lincoln and Grant – well, they defeated the Confederacy. (The protestors, however, drew no sharp distinctions between more and less “problematic” figures.) Which brings me to Gary Younge’s essay.

In a long read article for The Guardian, Younge takes the argument for removing “problematic” statues to its logical conclusion (or what he believes is its logical conclusion). In particular, he argues that “every single statue should come down”. Younge cannot be accused of inconsistency in respect of whom he deems worthy of commemoration:

So yes, take down the slave traders, imperial conquerors, colonial murderers, warmongers and genocidal exploiters. But while you’re at it, take down the freedom fighters, trade unionists, human rights champions and revolutionaries. Yes, remove Columbus, Leopold II, Colston and Rhodes. But take down Mandela, Gandhi, Seacole and Tubman, too.

His arguments, as I understand them, are fourfold. First, statues are a “fundamentally conservative” form of public art, which “represent the value system of the establishment at any given time”. Second, removing statues cannot be described as “erasing history” because statues are “symbols of reverence; they are not symbols of history”. And in any case removing them is just as much part of history as putting them up in the first place. Third, where a historical figure’s reputation is concerned, “there is no guarantee that any consensus will persist” – someone deemed great in the past may not be deemed great in the present. Fourth, statues “skew how we understand history itself” by assigning undue importance to the actions of certain individuals.

Interestingly, Younge’s arguments echo those of the libertarian historian Stephen Davies (or perhaps he prefers “classical liberal”). In July of last year, Davies argued, “We should take down ALL of the statues. There should be no public memorials of anybody.” Like Younge, Davies maintains that this is “not about history”, since removing statues “will not stop people writing about past figures and others reading and learning about them”. Moreover, he claims there is no shared memory that would justify keeping the statues on public display, and that trying to create one “is an act of collectivism”.

It should be noted that Davies does not want to see the statues hidden or destroyed. Rather – as you might have expected from an IEA man – he backs privatisation. Specifically, Davies wants to see the statues relocated to private parks and museums, where people could “express their consent” by paying to see them. In his words, “There is nothing wrong with memorialisation of past figures or the creation and nurturing of a shared memory if this is done privately and does not involve trying to claim a monopoly status.”

Both Younge and Davies’ arguments are worth reading and taking seriously. However, I’m not convinced that we should take down all the statues.

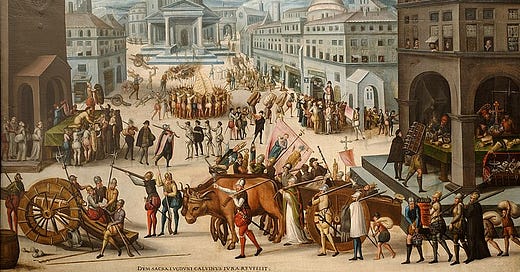

To begin with, the impulse to remove or destroy public monuments is nothing new. People have been toppling statues, defacing murals, felling figurines, blowing up Buddhas, and shattering stained-glass windows for thousands of years. This impulse even has a name: iconoclasm. Throughout history, iconoclastic acts were typically carried out by members of some new-fangled religious or political faction as a way of expunging the old order. And today’s statue removals are no exception. Whereas idolatrous images were offensive to 16th century Calvinists, colonialists and slave-traders are offensive to 21st century progressives.

Of course, it isn’t just left-wing activists that are engaged in iconoclasm today. Islamists, too, find meaning in the destruction of sacrilegious monuments. Back in 2001, the Taliban blew up the Buddhas of Bamiyan – two giant, 6th century statues in Afghanistan. And since 2014, ISIS has plundered or destroyed at least 28 historical buildings in the areas under its control, including sites dating back over 3,000 years. (You may recall videos of ISIS fighters smashing up ancient statues with sledgehammers.)

Now I assume that Younge and Davies wouldn’t support the recent Islamist actions, not least because the offending artefacts were actually destroyed (for the most part), rather than transferred to museums.

What’s the difference between Islamists removing monuments they don’t like, and left-wing activists removing monuments they don’t like (aside from the method of removal)? The main one, it seems, is the age of the monuments. ISIS destroyed sites that were thousands of years old, whereas left-wing activists toppled statues that were (at most) a few hundred years old. So unless Younge and Davies want to see the Temple of Bel and the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II turned into private museums, it’s not true that they want to take down every statue.

But there’s a more significant problem with the case for removing all statues. Younge and Davies’ are assuming that the entire debate is over statues – physical sculptures depicting historical figures that are displayed in public locations. However, it actually encompasses a far larger collection of objects: not only statues, but also flags, buildings, street names, place names and songs sung at Last Night of the Proms. In other words, it encompasses all publicly displayed objects that have the potential to offend at least someone. As I noted in a piece for RT last year:

… if statues of Columbus are a painful reminder of historical injustice, then the same must be true of the nation’s capital: Washington, District of Columbia. Statues of Columbus can at least be avoided (confined, as they are, to particular locations), but the nation’s capital is mentioned in the news almost every day. In fact, ‘Washington’ too is “problematic”, given that the man was a slave-owner, and someone may soon discover that ‘District’ has some hitherto unknown nefarious connotation.

Hence the true logical conclusion of the argument for removing “problematic” statues is to remove everything “problematic” from the public realm. This means: having no national flag (or certainly not one with negative historical connotations); demolishing or privatising all state-owned buildings with negative historical connotations; renaming all the streets with “problematic” names; renaming all the places with “problematic” names (including Washington D.C.); and definitely not singing ‘Rule Britannia!’ on Last Night of the Proms!

Perhaps Younge and Davies believe this would be a desirable state of affairs, but to me it seems rather unappealing. Not only would it be a royal nuisance to change or remove hundreds of objects just because a small number of people are offended by them, but – by severing our connection to the past – it would make the culture less interesting and less rich. This is not to say, incidentally, that no statue should ever be removed. I’m disputing the claim that they should all be taken down.

Image: Unknown, The Sack of Lyon by the Calvinists in 1562, circa 1565

Lockdown Sceptics

I’ve written five more short posts since last time. The first criticises a New York Times article that claimed Britain’s second wave was more deadly than the first. The second considers whether Britain should have tried to contain the virus using border controls. The third argues that care homes achieved a degree of focussed protection in the second wave. The fourth points out that Sweden’s mortality rate last year was lower than in 2015. The fifth summarises a study finding that the German R number has “no direct connection” with lockdown measures.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.