One of the major outstanding questions of the war in Ukraine is whether Europe should stop buying Russian energy. The US has already banned imports of Russian oil, gas and coal, and the UK plans to phase out oil imports by the end of the year. However, many European countries continue to buy millions of dollars of Russian energy every day. Indeed, the European Union is Russia’s single biggest customer in the natural gas market.

Ukrainian officials have repeatedly called for European leaders to halt these purchases. In a recent New York Times op-ed, one official said it was a “moral and strategic imperative” for Europe to “stop funding Mr. Putin’s war machine”. By halting purchases of Russian energy, Europe will advance the strategic goal of depriving the Russian state of much-needed hard currency, thereby hampering its capacity to wage war. But it will also advance the moral goal of exempting Europe from complicity in financing that war.

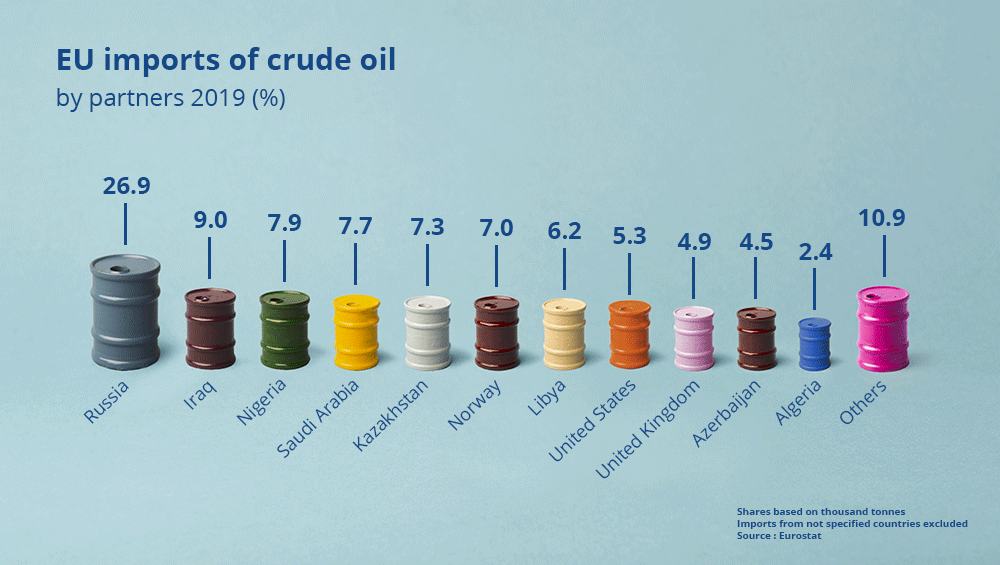

Before considering whether there is in fact an overwhelming moral case for Europe to stop buying Russian energy, it’s worth reviewing exactly how much of that energy Europe actually buys. The image below shows EU imports of crude oil, broken down by exporter, for the year 2019. Russia is by far the largest exporter, accounting for 27% of Europe’s crude oil imports.

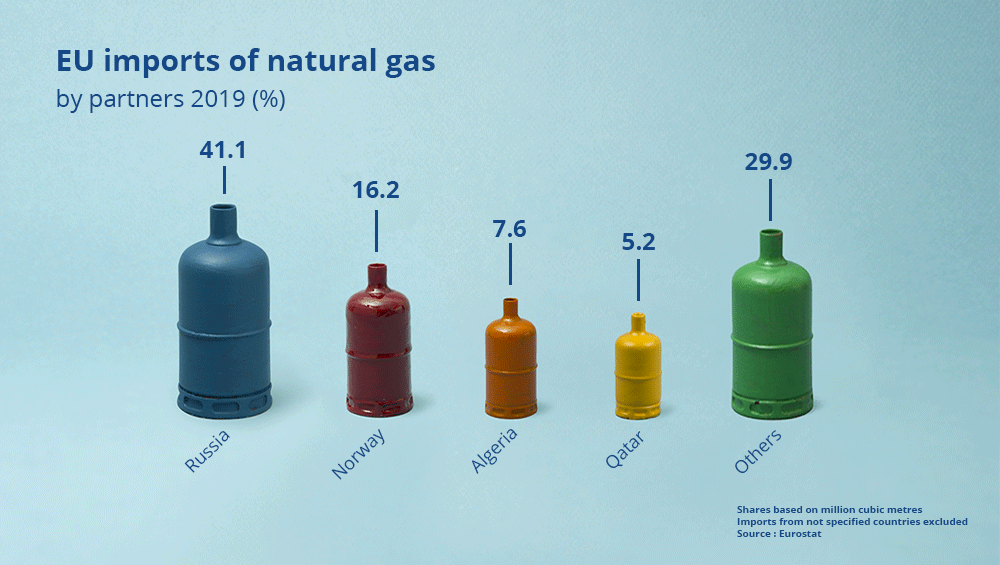

Likewise, the image below shows EU imports of natural gas, broken down by exporter, for the year 2019. Once again, Russia is by far the largest exporter, accounting for 41% of Europe’s natural gas imports. Specific countries are particularly reliant on Russian gas. For example, Germany gets 49% of its gas from Russia, while for Latvia, the figure is 93%. The EU also gets 47% of its solid fuel (mostly coal) from Russia.

Because of their dependence on Russian energy, several European countries – notably Germany – have expressed significant reservations about an energy embargo, so far blocking attempts to impose one. As the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz warned, “Sanctions must not hit European states harder than Russian leadership.” He was backed by the main German business lobby, which said in statement that cutting off Russian gas supplies would have “incalculable consequences”. On the other hand, a team of (mostly German) economists claims that an immediate embargo would only reduce the country’s GDP by 0.5–3%.

In appraising the moral case for Europe to stop buying Russian energy, one has to consider several things: the costs to ordinary Russians of diminished government spending; the costs to Europeans of scarcer or more expensive energy; the likelihood that halting energy purchases will bring an end to the fighting; and the possibility of acquiring energy from more “ethical” sources. There may be other things to consider, but these strike me as the most important.

The costs to ordinary Russians of diminished government spending might include reduced access to food and healthcare for those Russians who depend on state assistance. Now you might say that since Europe is under no obligation to continue buying Russian energy, it cannot be held responsible for the knock-on effects of reduced government revenues. However, an embargo would in this case involve breaking previously negotiated contracts, so it’s not the same as choosing not to buy Russian energy in the first place.

Another counterargument is that, insofar as they actively support Russia’s war in Ukraine, ordinary Russians are not innocent bystanders. And while at least one poll has found that a sizeable majority do support the war, it’s hard to know exactly how many respondents were answering honestly, or how they would respond if they had access to news sources other than state media. What’s more, even if a majority do support the war, there’s still a sizeable minority who don’t, and an embargo would entail collective punishment of all Russians.

The costs to Europeans of scarcer or more expensive energy would probably amount to an economic recession across much of the continent. Jobs would be lost, businesses would go bankrupt, and the standard of living would fall (albeit temporarily). Of course, if Europeans were aware of this but deemed halting Russian energy imports to be more important, then such costs would be borne voluntarily. However, it seems likely that many Europeans would not be willing to risk losing their jobs or seeing their business go bankrupt for the sake of an energy embargo against Russia. So even if democratically elected leaders did impose one, the negative effects on Europeans who didn’t consent still have to be counted on the costs side.

As to the likelihood that it will bring an end to the fighting, this is somewhat plausible, though by no means certain. While being deprived of hard currency would certainly hamper Russia’s capacity to wage war, a large amount of military spending is already “locked in”. The Russian state has probably already purchased most of the bullets, tanks, artillery, aircraft and missiles that it plans to deploy in this war. Consequently, a large short-term drop in government revenues might not be enough to force a withdrawal, even if it did necessitate cuts in soldiers’ pay. Remember that countries much poorer than Russia (such as North Korea) are able to maintain quite powerful militaries.

Richard Hanania has studied the empirical literature on sanctions in greater detail than me, and he concludes, “By and large, they do not work”. What’s more, rather than bringing about regime change through popular uprisings, they may even backfire, “making mass killing and repression more likely, while decreasing the probability of democratization.” Granted, an energy embargo against Russia has a better chance of working than your typical sanctions package, but it’s worth noting how little scholarly evidence there is that sanctions actually achieve their objectives.

However, even if an energy embargo fails to stop Putin’s tanks in their tracks, perhaps Europe has a moral obligation to impose one anyway – to avoid being complicit in financing his war. Which brings me to the last of the four considerations mentioned above: the possibility of acquiring energy from more “ethical” sources. In order to avoid a truly catastrophic recession, Europe would presumably have to make up most of the energy it is currently importing from Russia. Increasing domestic production would only go so far, since building new power stations takes time, as does integrating them into the existing infrastructure. So we are really talking about finding new exporters.

The table below lists the top ten oil exporters, indicating that Europe is not exactly spoilt for choice in terms of ethical alternatives. Indeed, the single biggest oil exporter (which already supplies 8% of Europe’s oil) is Saudi Arabia, a country that has been engaged in its own destructive foreign intervention since 2015 – the bombing campaign in Yemen. According to the Yemen Data Project, more than 8,600 Yemeni civilians have been killed in Saudi air strikes to date. There’s also Saudi Arabia’s ongoing fuel blockade of Yemen, which has pushed hundreds of thousands into extreme malnourishment.

Between 2015 and 2017, eight other nations were involved in the Saudi-led bombing campaign, including the UAE, Kuwait and Qatar – all major energy exporters. So from a moral standpoint, replacing Russian oil with oil from the gulf monarchies isn’t really an improvement. Indeed, if Europe is going to boycott Russian oil on the grounds that Russia is currently bombing civilians in a foreign country, it ought to boycott Saudi oil for the same reason. Note: Russia and Saudi Arabia account for almost 30% of global oil exports, meaning that any truly “ethical” imports policy will be rather expensive.

What about natural gas? Aside from Russia, the main exporters include Qatar, Norway and the United States. And in fact, the European Union has already reached an agreement with the US to begin importing large quantities of liquified natural gas. However, it is by no means clear that, when it comes to foreign policy, the US is any more ethical than Russia (even if its motives “sound” good). To take just one example, the US occupied Afghanistan for twenty years, prompting an insurgency that killed 70,000 Afghan soldiers and 46,000 civilians. After abruptly withdrawing last year, it then froze the country’s foreign exchange reserves, creating the conditions for a mass famine.

Of course, the US is a close ally of Europe, so it might make strategic sense to import American gas instead of Russian (even though the latter works out as cheaper). But the case has not been made that there’s a moral imperative for Europe to switch suppliers. Funding “America’s war machine” isn’t obviously more defensible than funding Russia’s.

And if Europe is only going to acquire energy from ethical sources, shouldn’t it extend that principle to trade in general? China is the EU’s single largest trading partner. Yet according to UN experts, as well as the governments of the US, UK, France, Canada and several other countries, it is engaged in an actual “genocide” against the Uyghur people. By purchasing billions of dollars of Chinese goods, isn’t Europe complicit in financing this repression? How can the EU continue trading with a country that some of its own member states have accused of “genocide”?

There is certainly a strategic case for Europe to stop buying Russian energy. However, the moral case doesn’t add up. Imposing an energy embargo would be a form of collective punishment against Russians, and would hurt both European consumers and European businesses. The policy might not bring an end to the fighting, and could lead the Russian state to become even more repressive. Most importantly, it’s not clear that alternative energy providers, like Saudi Arabia and the US, are any more ethical than Russia in the field of foreign policy.

Image: Russian Government, Dmitry Medvedev visits Zapolyarnoye gas field, 2013

The Daily Sceptic

I’ve written four more posts since last time. The first notes that excess mortality rates have been converging in Western Europe but not in Europe as a whole. The second notes that February’s age-standardised mortality rate in England was the second lowest on record. The third summarises a paper arguing that policymakers ignored standard welfare economics during the pandemic. The fourth asks whether lockdown caused the biggest drop in American happiness since surveys began.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

You consistently have opinions that belong to the dark side. It makes your opinions quite predictable. You will take the more pro Russian point of view and the more pro COVID point of view.