Quantifying COVID-19's lethality in Europe

There are several ways of quantifying COVID-19’s impact on mortality. One is to estimate the infection fatality rate (IFR) by dividing the number of deaths by the number of infected persons. This may not be an accurate method because when someone dies with COVID-19, it is not always possible to say whether he died of the disease or merely with the disease. Depending on what criteria are used for assigning deaths to COVID-19, one may end up underestimating or overestimating the true number of deaths. In addition, due to the large number of asymptomatic cases, it may be difficult to estimate the true number of infected persons without testing a large, representative sample of the population.

A second way of quantifying COVID-19’s lethality is to calculate the “excess deaths” by comparing the number of observed deaths from all causes in a particular time interval to the number that would be expected based on recent historical data. This method is arguably better than trying to estimate the IFR, but it is not wholly reliable. One problem is trying to estimate the expected number of deaths. Some sources use a simple five-year average. However, this will underestimate the expected number of deaths in most Western countries because these populations are ageing, meaning that the absolute number of people at risk of dying is increasing each year. And because of the “dry tinder” effect, if the number of deaths was below-trend in the last one or two years, it is more likely to be above trend in the next year.

Another – albeit minor – problem with calculating excess deaths is that people dying of COVID-19 appear to be slightly older than people dying of all other causes, at least in the UK (and presumably most other Western countries). Since what we really care about is total life-years lost, excess deaths will slightly overstate COVID-19’s impact on mortality.

A third way of quantifying COVID-19’s lethality is to compare age-standardised measures of mortality in different years (or in similar populations that have been differentially exposed to COVID-19). The advantage of this method is that it controls for over-time and cross-country differences in population age-structure. As noted in my last newsletter, the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) has computed the age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR) in England and Wales for the first ten months of the year, each year, going back to 2001. Their figures indicate that the risk of mortality in 2020 has been higher than every year since 2008 in England. I estimated that the overall effect of COVID-19 has been to temporarily reduce life expectancy in England by 1.2–1.4 years.

Based on cross-country comparisons of the crude COVID-19 death rate, England appears to have been one of the worst-affected countries in Europe. Other European countries that appear to have been badly affected include: Belgium, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, France and Sweden. However, cross-country comparisons of the crude COVID-19 death rate could be affected by both differences in population age-structure and differences in the criteria used for assigning deaths to COVID-19. A country whose medical system is “liberal” when assigning deaths to COVID-19 will appear to have been more badly affected than one whose medical system is “conservative” when assigning deaths to COVID-19. What does the picture look like when we use an age-adjusted measure of all-cause mortality?

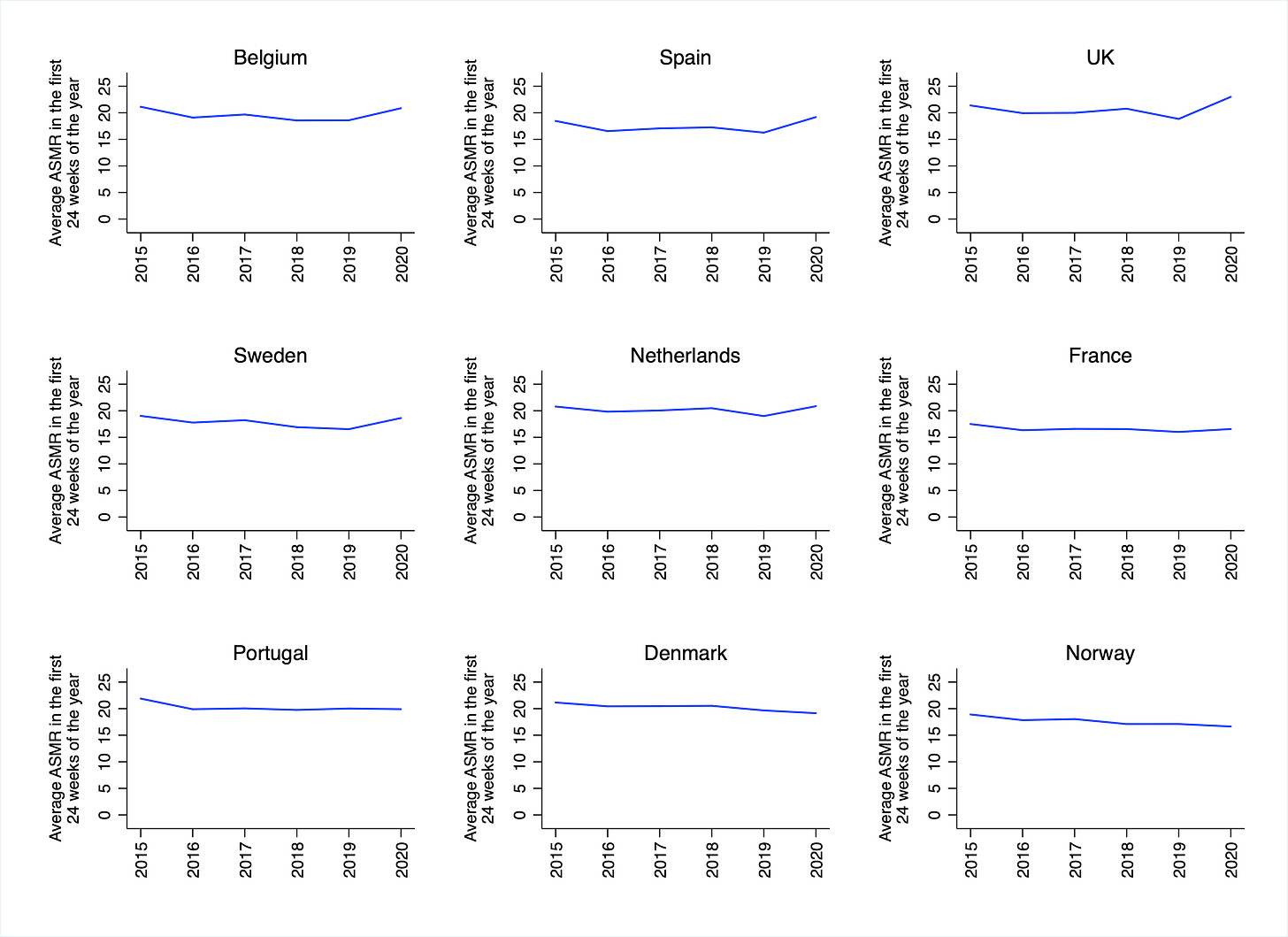

The ONS has computed weekly ASMRs for 2015–2019, as well as the first ~24 weeks of 2020, in most European countries. Details about their methodology are given in a section titled ‘Measuring the data’. As they note, the ASMR is the weighted average of the age-specific mortality rates, with weights equal to the proportion of people in the corresponding age groups of the European Standard Population. Week 24 of 2020 ended on 12 June, which is past the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in every European country, but well before the beginning of the second wave. Using the ONS’s figures, I computed the average ASMR in the first 24 weeks of the year in a selection of European countries. These are shown in the chart below. (Italy is not shown because it did not report data all the way up to week 24.)

There is a noticeable uptick in the ASMR in Belgium, Spain, the UK, Sweden and the Netherlands. There is a small uptick in France, and no uptick in Portugal, Denmark or Norway. This is broadly consistent with the picture one obtains from cross-country comparisons of the crude COVID-19 death rate. However, it is worth putting the increases in mortality observed in countries like Belgium and the UK into context. For example, the average ASMR in the first 24 weeks of 2020 in the UK was lower than the typical ASMR in most of Eastern Europe. As the ONS notes, “the highest mortality rate observed during a “normal” winter in Bulgaria has historically been greater than the highest mortality rate observed during the “abnormal” coronavirus pandemic in England.”

Similarly, the average ASMR in the first 24 weeks of 2020 in Sweden was lower than the average ASMR in the same period in Denmark, even though Denmark has not seen any uptick in mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. And although France saw a small uptick in mortality during the first 24 weeks of 2020, its average ASMR in that period was lower than the corresponding figure in every other major European country except Switzerland.

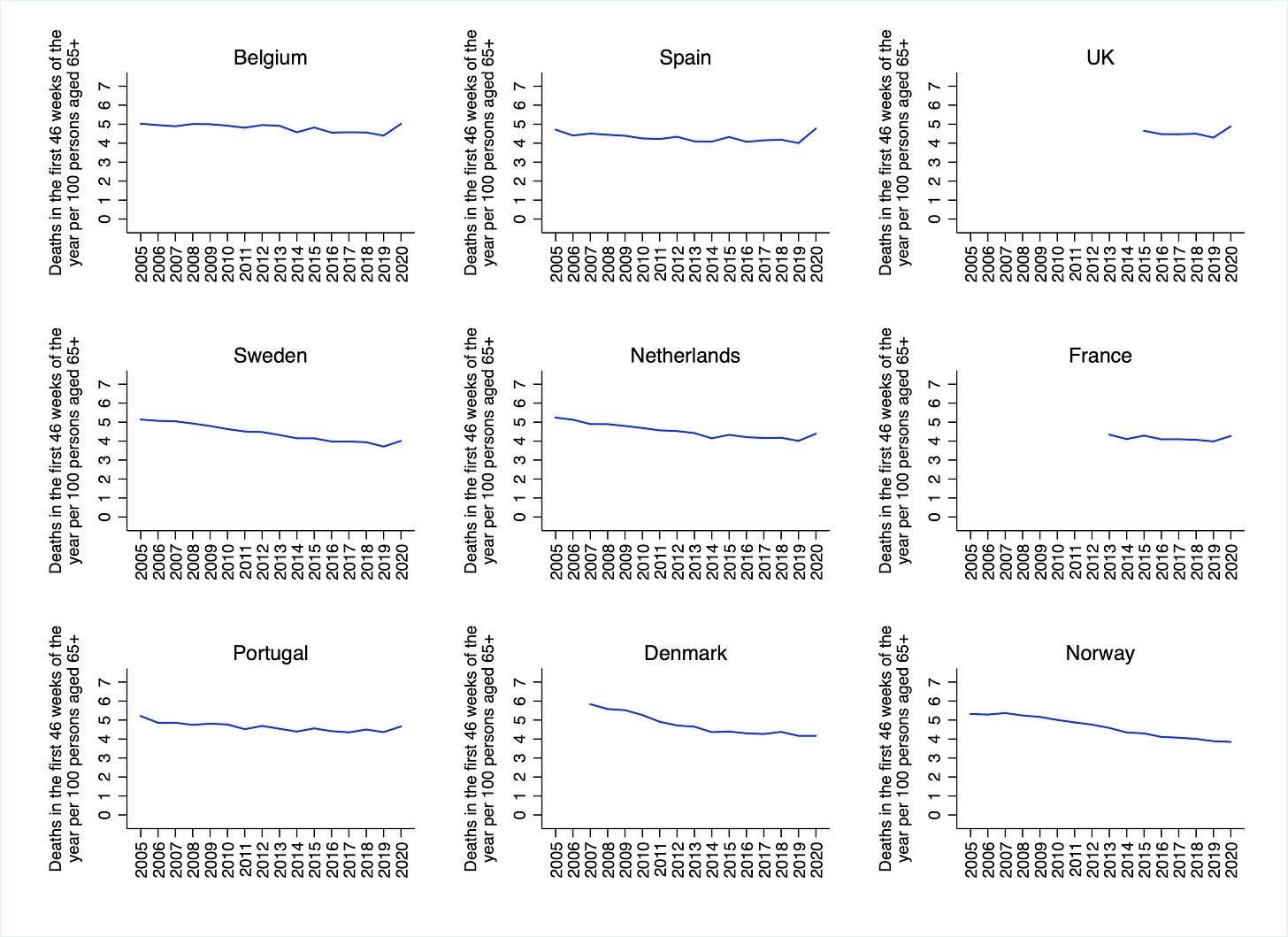

Of course, the ONS’s figures only capture the increase in mortality associated with the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas some European countries have experienced a second wave of deaths. (The ONS apparently intends to update its analysis at some point). In order to calculate an age-adjusted measure of mortality for a longer portion of 2020, I obtained weekly data on the absolute number of deaths, and yearly data on the absolute number of persons aged 65+, from Eurostat. I then computed the number of deaths in the first 46 weeks of the year per 100 persons aged 65+, in each year going back to 2005. (For some countries, the data did not go back as far as 2005.)

The reason I did not compute ASMRs is simply that doing so would have been too time-consuming. (It would have required downloading and merging datasets corresponding to each 5-year age group for the number deaths, the number of persons, and the proportion of people in the European Standard Population.) The measure I have calculated should only be considered a rough measure of age-adjusted mortality. (Incidentally, the reason I used the number of persons aged 65+ as the denominator is that this corresponds to the age-group in which the vast majority of deaths take place. For example, in the UK’s 2015 life table, 90% of persons were still alive at age 64.) Figures are shown in the chart below.

Unsurprisingly, the picture for the most recent years is more-or-less the same as in the first chart. There is a noticeable uptick in mortality in Belgium, Spain, the UK, Sweden and the Netherlands. There is a small uptick in France and Portugal, and no uptick in Denmark or Norway. Once again, however, the increases in mortality should be put into context. For example, in Belgium the number of deaths in the first 46 weeks of the year per 100 persons aged 65+ was higher in 2005 than it was in 2020. In the Netherlands, it was higher in 2013. And In Sweden, it was higher in 2015. In Spain, by contrast, that number was higher in 2020 than in every year going back to 2005.

As mentioned above, the age-adjusted measure of mortality I calculated should only be considered approximate, since it does not account for differences in age-specific mortality within the broad 65+ age-group. And because the number of persons aged 65+ was not available for 2020, I had to use the value for 2019 instead. Hopefully, the ONS will soon update its analysis of weekly age-standardised mortality rates, so that there will be a comprehensive picture of COVID-19’s lethality in Europe.

Image: Michiel Sweerts, Plague in an Ancient City, 1654

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.