Misinformation in the age of COVID

For the last eighteen months, governments around the world have been battling the novel coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China. Millions of people have died, and millions more have lost their businesses, missed out on schooling, or fallen into poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic is undoubtedly the biggest crisis the world has faced since the Second World War.

Unfortunately, however, the response to COVID-19 has been severely hampered by a small group of actors spreading dangerous misinformation. Although there’s no universally-agreed term for this group, I shall employ the one that seems clearest and most appropriate in the context: lockdown proponents. It’s difficult to know precisely who the lockdown proponents are, but they appear to comprise mostly academics, teachers and journalists. Sources indicate that their money comes primarily from taxpayer-funded salaries.

We should remember that mistakes and errors have been made by people on both sides of the lockdown debate. However, those made by the lockdown proponents have been far more consequential. This small group (of which we knew almost nothing prior to the outbreak of COVID-19) has had the ear of most Western governments since the crisis began. In the UK, their influence runs mainly through a clandestine organisation known as SAGE, whose early meetings were attended by the mastermind of the Vote Leave campaign, Dominic Cummings. And note: it was only thanks to the legal challenge brought by Simon Dolan that we even have access to minutes of the SAGE meetings.

What sort of misinformation have the lockdown proponents been spreading? To begin with, they presented lockdowns as the “scientific” response to the pandemic, repeatedly demanding that we “follow the science”, while they dismissed alternative strategies as “wrong scientifically”. What they didn’t mention is that lockdowns represent a radical departure from pandemic management science.

For example, the ‘UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy 2011’ says that attempting to halt the spread of a “would be a waste of public health resources”, while the WHO advised in 2019 that “quarantine of exposed individuals” is “not recommended in any circumstances”. And in a 2006 paper, four top scientists (including Donald Henderson, who led the effort to eradicate smallpox) said of large-scale quarantine that “this measure should be eliminated from serious consideration”.

What’s more, members of SAGE (the secretive organisation that gave the intellectual backing for lockdowns) rejected the only measure that might have allowed us to contain the virus, i.e., border controls. Minutes of the SAGE meeting on 22 January record that “NERVTAG does not advise port of entry screening”. And minutes of the meeting on 4 February indicate that those present believed travel restrictions “would be of limited value”. Why was the UK government taking advice from these reckless border control deniers?

Let’s turn to “the science” we’ve been told to follow. Much of it is based on dubious epidemiological models that frequently assume what they set out to prove (i.e., that only lockdowns have a large effect on transmission). Just like Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, the creators of these models use euphemisms to obscure what they’re really talking about. They’ll refer to “non-pharmaceutical interventions” when what they mean is: shutting schools and businesses, and confining people in their homes. How well have these models done at predicting the epidemic’s trajectory? Not well enough to justify their extraordinary influence, that’s for sure.

A crucial test case for any model of the COVID-19 pandemic is Sweden during the first wave. That’s because Sweden – known for its high levels of trust and tolerance of refugees – was the only Western country that refused to implement a national lockdown. (There were zero days of mandatory business closures and zero days of mandatory stay-at-home orders.) The hugely influential Imperial College model predicted 85,000 deaths in Sweden. And a model devised by Uppsala University researchers, which was “based on work by” Neil Ferguson’s team, predicted 96,000 deaths. To date, however, there have been just 14,657. And even that figure’s an overestimate.

What other misinformation have lockdown proponents been spreading? In his latest book, the SAGE member Jeremy Farrar claims that Dominic Cummings “wanted to run an aggressive press campaign against those behind the Great Barrington Declaration and others opposed to blanket Covid-19 restrictions”. (Cummings, you’ll recall, masterminded the Vote Leave campaign.)

Referring to the quotation above, two authors of the Great Barrington Declaration – Professor Martin Kuldorff and Professor Jay Bhattacharya – note that they have faced “multiple distortions, misinformation, ad hominem attacks and outright slander”. For example, opponents have mischaracterised focussed protection as a “herd immunity strategy”, which the authors say is like describing a pilot’s plan to land a plane as a “gravity strategy”. After all, any sensible plan for dealing with COVID-19 involves the build up of immunity in the population – whether from vaccines, natural infection or some combination of the two.

And what about the costs of lockdown? Proponents are complicit in what is arguably the greatest assault on civil liberties since the end of World War II. Yet they’ve attempted to conceal this fact by misrepresenting their opponents, and getting them censored on social media.

The Siracusa Principles, which were adopted by the UN Economic and Social Council in 1984, set out the criteria that responses to national emergencies must fulfil in order to safeguard human rights. These include being strictly necessary, respectful of human dignity, and subject to review. Yet the UK’s lockdowns, as the barrister Francis Hoar has argued, failed to meet several of these criteria. For example, they initially proscribed all political gatherings and public demonstrations without exception (a favourite tactic of authoritarian dictators). The public has a right to know why the government has been relying for its advice on civil liberties doubters and human rights sceptics.

Let’s talk about the economic costs of lockdown. These too proponents have sought to downplay. Chris Whitty, the Chief Medical Officer for England, has claimed that “it’s a false dichotomy to talk about health versus wealth”. (Though back in March of 2020 he said, “what we’re very keen to do is not intervene until the point we absolutely have to, so as to minimise economic and social disruption.”)

Is it really a “false dichotomy” to suggest that shuttering the economy for months on end might come with some costs? Of course not. The argument that there’s no trade-off only works if locking down allows you to completely suppress the virus, which England’s lockdowns clearly did not do (and probably could not do – absent Chinese levels of repression). There’s plenty of evidence that lockdowns hurt the economy over and above the effect of voluntary social distancing. And these costs were not trivial; thousands of people lost their businesses, and the UK added tens of billions to its national debt.

Since the start of the pandemic, governments across the Western world have been in thrall to a small group of actors spreading dangerous misinformation. These lockdown proponents can count among their number not only border control deniers, but also civil liberties doubters, human rights sceptics, and collateral damage minimisers. Though I don’t call for censorship, I would advise readers to guard themselves against the misleading claims spread by lockdown proponents, so that we’re all better prepared for the next pandemic.

Please note: this article is written in a satirical tone. I do not believe that all or even most lockdown proponents argue in bad faith, or that terms like “border control deniers”, “civil liberties doubters” and “human rights sceptics" are useful in this context. The point of my article is to illustrate how easy it is to accuse others of spreading “misinformation”.

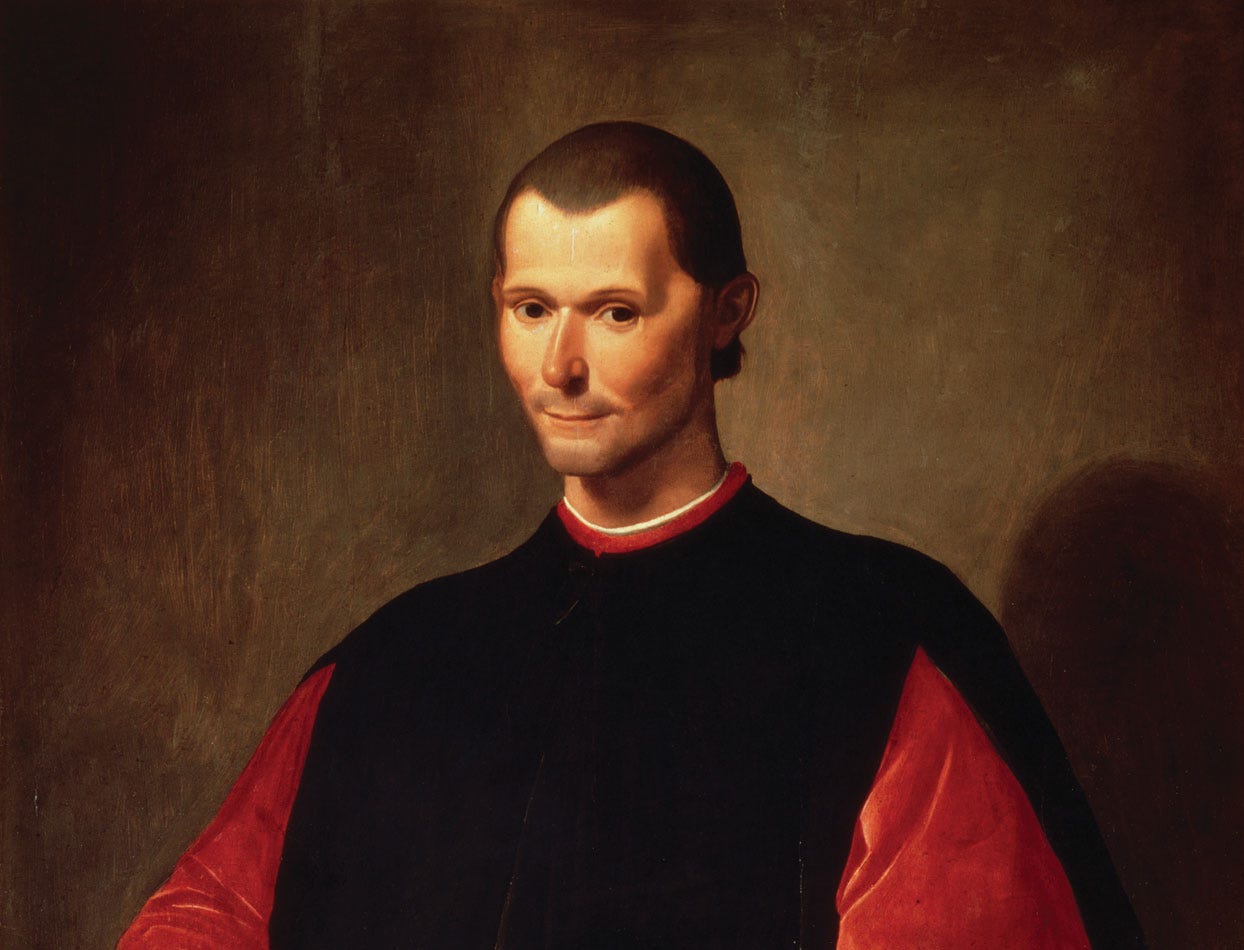

Image: Santi di Tito, Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli, 16th century

The Daily Sceptic

I’ve written three more posts since last time. The first explains what I’d ask Boris and the boffins if I were present at one of the government’s press briefings. The second responds to arguments that have been made for removing sex from the public portion of birth certificates. The third comprises an interview with the researcher Philippe Lemoine. Incidentally, I really would recommend this interview; Philippe is an especially diligent and tenacious researcher, and his commentary on the pandemic has been essential reading.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.