Lockdowns and GDP growth in the EU

As I noted in a previous newsletter, the contraction in GDP last year was much larger than the contraction associated with the global financial crisis. There are two competing accounts of the “COVID-19 Recession”, as Wikipedia calls it. One claims that the reduction in economic activity is entirely due to voluntary behaviour change on the part of citizens. Another claims that it is due to both voluntary behaviour change and enforced lockdowns.

According to the first account, countries that experienced more severe epidemics saw greater behavioural change on the part of citizens. This account predicts that measures of epidemic severity should predict GDP growth even when controlling for government lockdowns. According to the second account, countries that experienced longer and more stringent lockdowns saw greater reductions in economic activity. This account predicts that measures of lockdown intensity/duration should predict GDP growth even when controlling for epidemic severity.

The first account assumes that lockdowns had no effect on GDP growth, since all the reduction in economic activity was due to citizens changing their behaviour. In other words, it assumes that people would have changed their behaviour to the same extent even in the absence of lockdowns. In the UK, both the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Chief Medical Officer have claimed there is no trade-off between health and the economy. (Likewise, in a recent paper, the economist Angus Deaton refers to the “supposed trade-off between deaths and income”.)

Contrary to these claims, numerous papers have found that lockdowns reduce economic activity. And in a recent survey of academic economists, a majority said there is at least some trade-off. I decided to carry out my own (very preliminary) test of the two competing accounts. Data on real GDP growth were taken from the IMF. Data on pandemic severity were taken from Our World in Data. And data on lockdown duration were taken from the Oxford Blavatnik School.

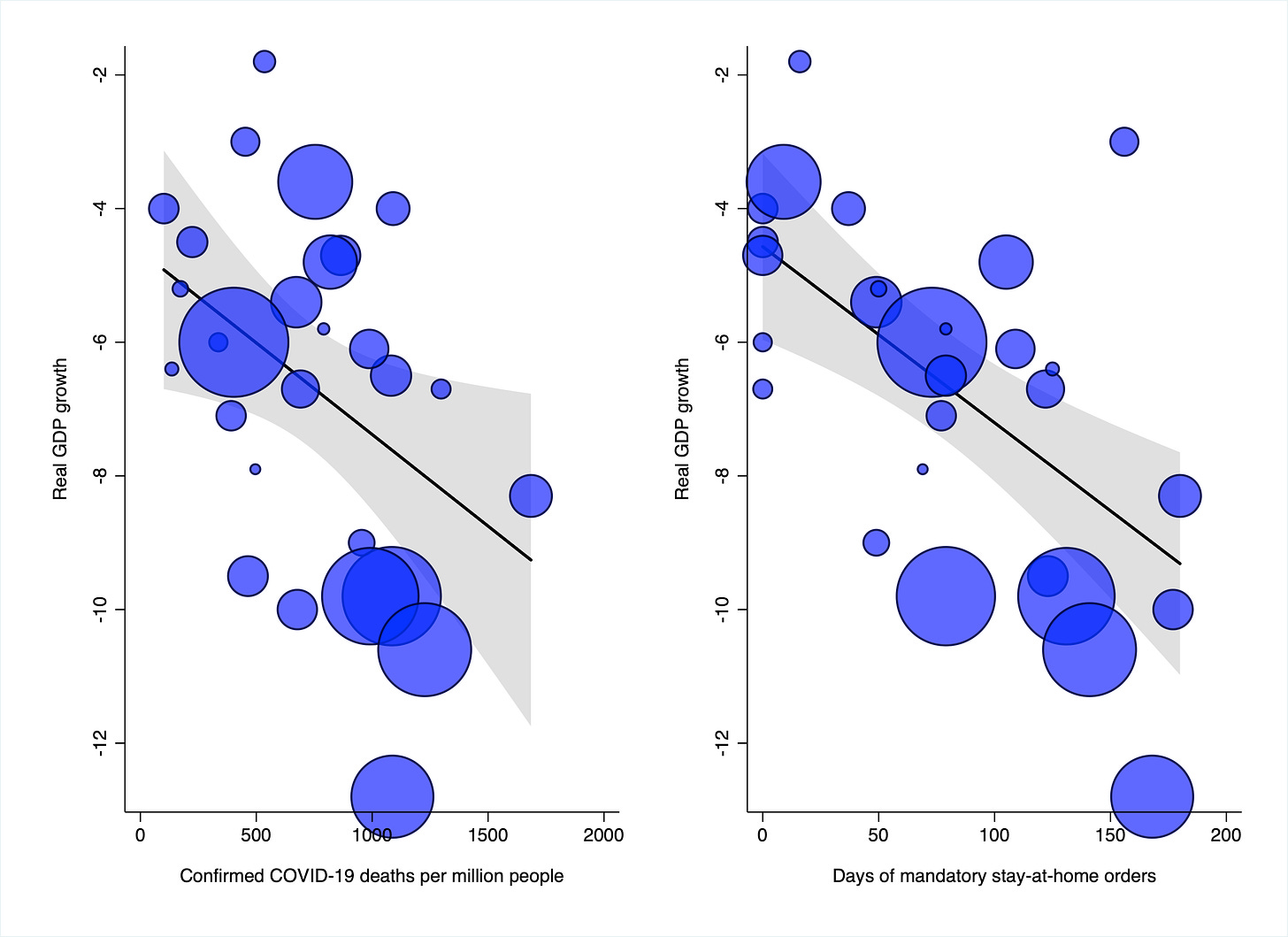

Confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people up to 31 December was used as a measure of epidemic severity. This measure was chosen in preference to confirmed cases per million people on the grounds that testing arrangements may differ across countries, and that people are more likely to change their behaviour in response to deaths. Number of days of mandatory stay-at-home orders (in any part of the country) was used as a measure of lockdown duration. This measure was chosen on the basis that stay-at-home orders, which confine both business owners and customers to their homes, are the most stringent of all the lockdown measures.

I decided to limit my sample to the 27 EU member states, plus the UK. This was done for two reasons. First, COVID-19 data from poor countries may not be reliable, due to lack of testing infrastructure. And second, the EU member states are subject to common rules and regulations, meaning that more factors are “held constant” when comparing them. According to data from the IMF (which are subject to revision), the EU’s GDP contracted by 7.6% last year, as compared to 4.2% in 2009. Hence the COVID-19 Recession was approximately 80% worse – in terms of lost output – than the so-called Great Recession.

The chart below shows the relationship between real GDP growth in 2020 and the two predictor variables of interest: confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people on the left, and days of mandatory stay-at-home orders on the right. Both relationships are negative and significant (left-hand panel: r = –.42 p = 0.028; right-hand panel: r = –.60, p < 0.001). Note that the circles are proportional to countries’ population sizes, but the slopes are unweighted.

In order to test the two competing accounts of Europe’s COVID-19 Recession, I ran a linear regression model of real GDP growth. When both predictor variables were included in the model, days of mandatory stay-at-home orders remained statistically significant, whereas confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people did not reach statistical significance. Hence in this rather crude model, lockdown duration was a stronger and more robust predictor of the reduction in economic activity than epidemic severity.

The usual caveats apply, of course. This is a very simple analysis, and none of the effects should be interpreted causally. But the results are still interesting. They suggest, along with the more comprehensive academic studies cited above, that there is a trade-off between health and the economy – at least for those countries that did not manage to contain the virus at the beginning.

Image: Axel Fahlcrantz, Solnedgång över hav

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.