Lockdown wasn't worth it

Aside from its effects on health, education and the economy, lockdown represents the greatest infringement on civil liberties in modern history. Here and elsewhere, the state used its monopoly on force to outlaw some of the most basic human interactions, such as having a meal with friends. Was it all worth it?

To answer that question comprehensively, we need to know: how much higher mortality would have been in the absence of lockdown; how much harm lockdown has caused in areas like health, education, the economy and civil liberties; and how much we value preventing deaths versus preventing lockdown harms. (In cost-benefit analyses, value is usually quantified in monetary units, such as pounds.)

Neither the costs nor benefits of lockdown are straightforward to estimate. One way to estimate the benefits is to assume that each life-year saved is “worth” £30,000 pounds, which is how much the NHS will pay to extend a patient’s life by one year. Analyses that have taken this approach find that the costs of Britain’s lockdowns substantially outweighed the benefits. However, one can always quibble with their assumptions.

Another issue is specifying the counterfactual. Lockdown might not look too bad relative to the counterfactual of doing nothing. But what if instead of “letting the virus rip”, we’d tried focused protection – the strategy outlined in the Great Barrington Declaration. In that case, the expected benefits of lockdown would be far lower.

I’m convinced that a well-executed focused protection strategy could have saved as or more lives than lockdown. However, suppose for the sake of argument that mortality would have been twice as high under focused protection. Note: this seems very unlikely, given that Sweden has actually had less excess mortality than the UK, and indeed most other countries in Europe.

Last year, Britain’s life expectancy fell by about 1.1 years. That means it would have fallen by an additional 1.1 years under focused protection. Is this figure large enough to justify the manifold harms of lockdown?

I would argue: no. Although 1.1 years is a large year-on-year change, it only takes us back 12 years in terms of rising life expectancy. In other words: to find a year in which mortality was as high as it was in 2020, we only need to go back to 2008. I remember 2008; it wasn’t full of front-page headlines about sky-high death rates. Aside from the financial crisis, people just got on with their lives.

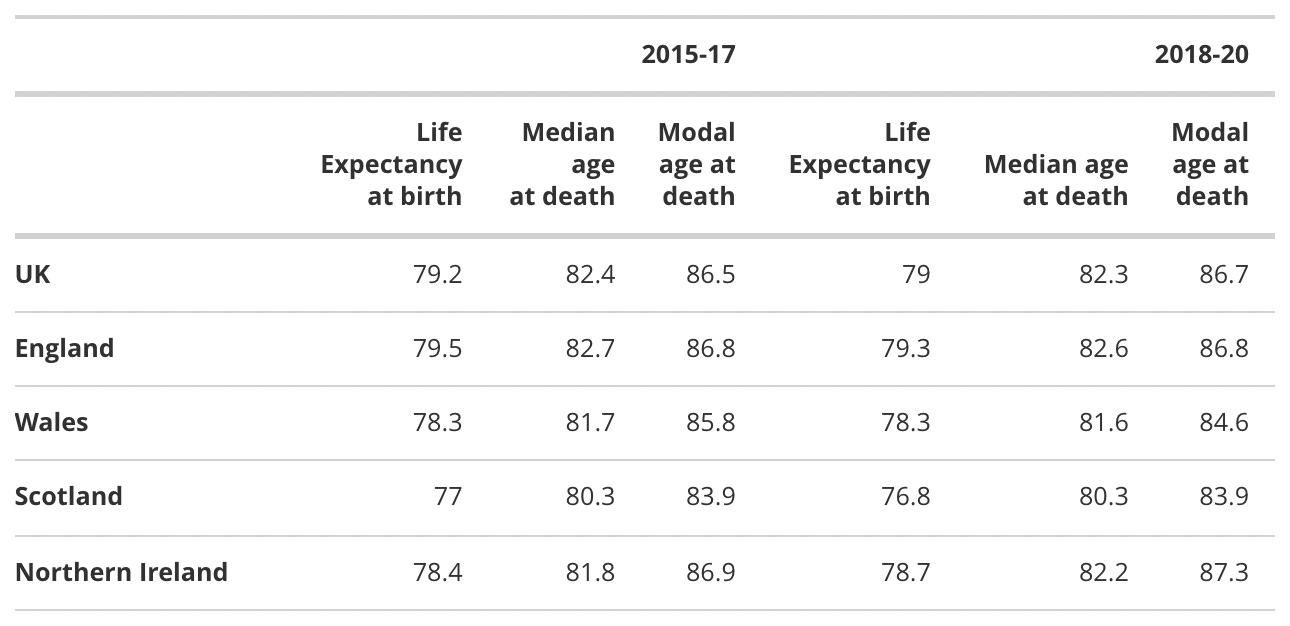

What’s more, 1.1 years is less than half the difference in life expectancy between Scotland and England. Each year, in other words, Scotland has a pandemic’s worth of mortality more than England. And yet we don’t make a big deal out of it. (Scotland even has net inward migration from the rest of the UK.)

Suppose at the start of 2020, the government had said, “In order to prevent mortality falling to the level of Scotland, we’re going to undertake the greatest infringement on civil liberties in modern history. Thanks to our measures, it will only fall to the level of Wales instead.” I suspect that public support for lockdown would have been much lower. Of course, the government didn’t know this in advance, but you get my point.

To repeat, I consider it highly implausible that mortality would have been twice as high under focussed protection. At most, it might have been 20 or 30% higher. And yet, even when we make this unrealistic assumption, it’s difficult to believe that lockdown was worth it.

Image: The Palace of Westminster in London, 2008

Women and wokeness

My previous newsletter argued that the influx of women into academia was one cause of the Great Awokening. However, in summarising the previous literature, I overlooked one important contribution: Edward Dutton’s book Witches, Feminism and the Fall of the West. Here’s an excerpt:

With sexual equality, females will be appointed over males as they will tend to be easier to work with, having higher Conscientiousness and higher Agreeableness. They will be what Bruce Charlton has called the “Head Girl” types, the kinds of popular and academically high-achieving, though conformist, females who are appointed head prefects at British girls’ secondary schools … The growth in the presence of these kinds of women at universities has fundamentally changed the culture of academia, rendering it less focused on the unbridled pursuit of truth.

And by complete coincidence, on the same day I published my newsletter, Mary Harrington wrote a piece for The Critic exploring similar themes. Here’s an excerpt:

“Administrative bloat” has been a remarked on feature of higher education for some time … Less remarked on is the sex breakdown of the growing proportion of administrators. A recent diversity and inclusion report by the University of California indicates that women make up more than 70 per cent of non academic staff … And that support system has an increasingly symbiotic relationship with student activism

Both Dutton’s book and Harrington’s article are well worth reading.

The Daily Sceptic

I’ve written four more posts since last time. The first documents that, before editorialising in favour of lockdowns, major left-wing newspapers described China’s lockdown as “terrifying” and “unprecedented”. The second notes that October’s age-standardised mortality rate in England was almost exactly equal to the five-year average. The third summarises a recent article arguing that epidemiological models have done badly because they ignored population structure. The fourth asks whether lockdown made us fat.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.