Is there "zero evidence" for hereditarianism?

In her book The Genetic Lottery, Paige Harden claims “there is zero evidence that genetics explains racial differences in outcomes like education”. And in an earlier 2017 article, she and her co-authors referred to Charles Murray’s arguments concerning race and IQ as “junk science”, which is how another scientist recently described Emil Kirkegaard’s research.

It is, of course, quite false to claim there is “zero evidence” for hereditarianism. There's the relative stability of the black-white IQ gap. There’s fact the gap is larger on more heritable and more g-loaded sub-tests. There’s measurement invariance and the absence of plausible X-factors. “But this is all indirect evidence,” critics will say. What about direct evidence from DNA itself?

In the last few years, at least two kinds of direct evidence have been adduced.

The first comes from comparisons of average polygenic scores across groups. An individual’s polygenic score for a certain trait is the weighted sum of all relevant variants (either positive or negative) that he or she carries, with weights equal to the effect sizes from GWAS studies. Although there are polygenic scores for both education and IQ, the former are more widely used, as they’re based on much larger samples.

When you calculate the average education polygenic score in different groups, you find that it is higher in whites than in blacks. This is obviously consistent with hereditarianism.

However, such evidence is frequently dismissed on the grounds that you can’t compare polygenic scores across groups. Why not? The polygenic scores that we currently have are based on data from Europeans, since all the relevant studies have been done in Western countries. And these scores have less predictive validity among non-Europeans (e.g., African Americans.)

The reason for this has to do with how variants are identified in GWAS studies. As you may recall from my earlier post on that subject, when people take part in a GWAS study, they aren’t genotyped at every single position along the genome. Rather, they’re genotyped at a subset of positions called single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs (pronounced “snips”). And researchers can get away with doing this because of something called “linkage disequilibrium” or LD for short.

Basically, different positions along the genome are not statistically independent of one another. For example, if you have an A at position 23, you’re much likely to have a G at position 46; whereas if you have a T at position 23, you’re much more likely to have a C at position 46. So once you’ve genotyped someone at all the SNPs, you don’t get that much more information by genotyping them at all the other positions in the genome.

What this means, however, is that when researchers identify an SNP associated with the trait in question, they can’t be sure whether that specific SNP is causal or whether it’s merely in LD with the causal variant.

Suppose you find that people with an A at position 23 have slightly higher IQ than those with a T at that position. This could be because having an A at position 23 changes the protein, which has various downstream effects that result in slightly higher IQ. However, it could also be because people with an A at position 23 are more likely to have a G at position 46, and it’s the G at position at 46 that changes the protein and causes higher IQ.

This would matter less if we were just comparing polygenic scores among individuals from the same race. But as it happens, patterns of LD across the genome differ substantially between races (undermining the argument that “race is a social construct”). In other words, while there might be a strong tendency for Europeans with an A at position 23 to have a G at position 46, there might be no such tendency among Africans.

So when researchers genotype Africans at all the SNPs used in European GWAS studies, there’s still a lot information missing. And the corresponding polygenic scores don’t work nearly as well.

It remains to be seen precisely how much this issue matters for comparisons of polygenic scores across groups. (Fuerst and colleagues created a “psuedo” polygenic score by weighting random SNPs with the GWAS effect sizes, and found that it was much less predictive than the true polygenic score for education. Which suggests the latter was not simply acting as a proxy for European ancestry.) However, the issue does have to be taken seriously.

This brings me to the second kind of direct evidence for hereditarianism: admixture analysis. Due to mating patterns in the past, blacks in the U.S. have about 20% European ancestry or “admixture”, on average. Looking at the relationship between ancestry and IQ within the black population therefore provides some insight into the causes of the black-white IQ gap.

As a matter of fact, Richard Nisbett (co-author of the 2017 article that accused Charles Murray of peddling “junk science”) has explicitly endorsed admixture analysis as a method for testing hereditarianism. In the appendix to his 2009 book Intelligence and How to Get It, he describes admixture analysis as “by far the most direct way to assess the contribution of genes versus the environment to the black/white IQ gap”.

What’s more, there are already numerous papers in the published literature that have used admixture analysis to study racial disparities in other traits.

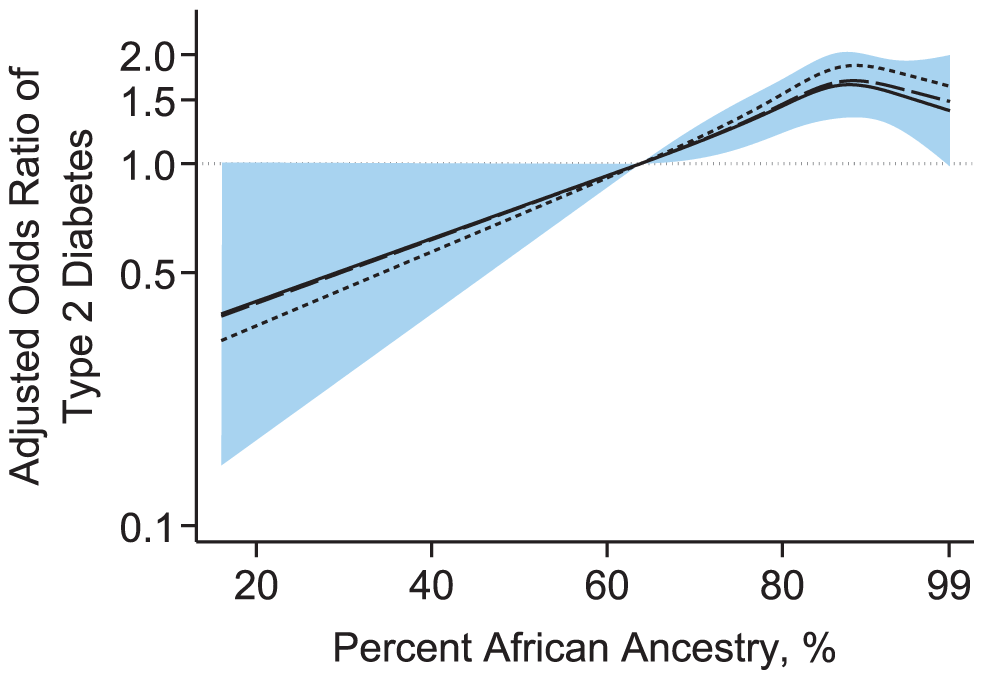

To take one example: David Reich and colleagues used the method to study why African Americans have higher rates of type 2 diabetes. They hypothesised that “some diabetes susceptibility alleles are present at higher frequency in African Americans than in European Americans, resulting in association between genetic ancestry and diabetes risk that is independent of its association with other non-genetic risk factors”. Their analysis supported this hypothesis.

There’s no scientific reason why admixture analysis can be applied to the racial gap in risk of type 2 diabetes, but not to the black-white IQ gap. Hence if someone insists that hereditarian studies using admixture analysis are “junk science”, they need to explain why all the other studies using this method are not.

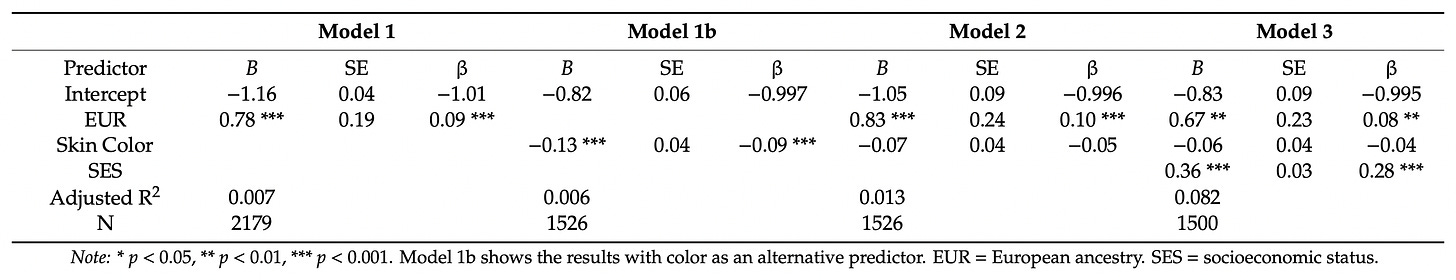

And what about those hereditarian studies? A positive association between IQ and European ancestry among blacks has now been shown in at least four different datasets. There’s the 2019 paper by Emil Kirkegaard and colleagues; there’s the 2019 paper by Jordan Lasker and colleagues; there’s the 2020 paper by Russell Warne; and there’s the 2021 paper by John Fuerst and colleagues.

Particularly compelling is the paper by Lasker and colleagues. They not only found the correlation between European ancestry and IQ among blacks, but also found that it was robust to controlling for a measure of skin colour and a measure of socio-economic status.

Now, these studies are not unimpeachable. (Nothing in science is.) Yet they do provide direct evidence for hereditarianism that doesn’t rely on heavily contested polygenic score comparisons. What’s more, they utilise a method that’s been employed in dozens of other studies, and which one prominent environmentalist described as “by far the most direct way” to test hereditarianism.

It’s up to environmentalists to explain how the findings of admixture studies can be reconciled with 100% environmental causation of the black-white IQ gap.

Image: Sybil Eysenck, Hans Eyesenck, German-born British psychologist

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.