Is COVID-19 deaths per capita a valid measure of the disease's lethality?

Since the beginning of the pandemic, one of the key metrics on which countries have been compared is COVID-19 deaths per capita. This statistic is reported by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre, by Our World in Data’s COVID-19 data portal, and by Worldometer’s COVID-19 data portal. It has mostly been taken for granted that COVID-19 deaths per capita constitutes a valid measure of the disease’s lethality, i.e., that more people have died from COVID-19 in countries with a high number of COVID-19 deaths per capita, and that fewer people have died in countries with a low number of COVID-19 deaths per capita.

However, because of cross-country differences in how COVID-19 deaths are counted, the measure might not accurately track the disease’s lethality. For example, if one country’s medical system is very “liberal” when assigning deaths to COVID-19, while another country’s medical system is very “conservative”, the former will appear to have a higher number of COVID-19 deaths per capita, even if there is no actual difference in the number who have died from the disease. Working out whether someone died of or merely with COVID-19 is difficult because the disease is novel and hence not yet fully-understood, and because the disease is most likely to kill persons who have one or more pre-existing conditions.

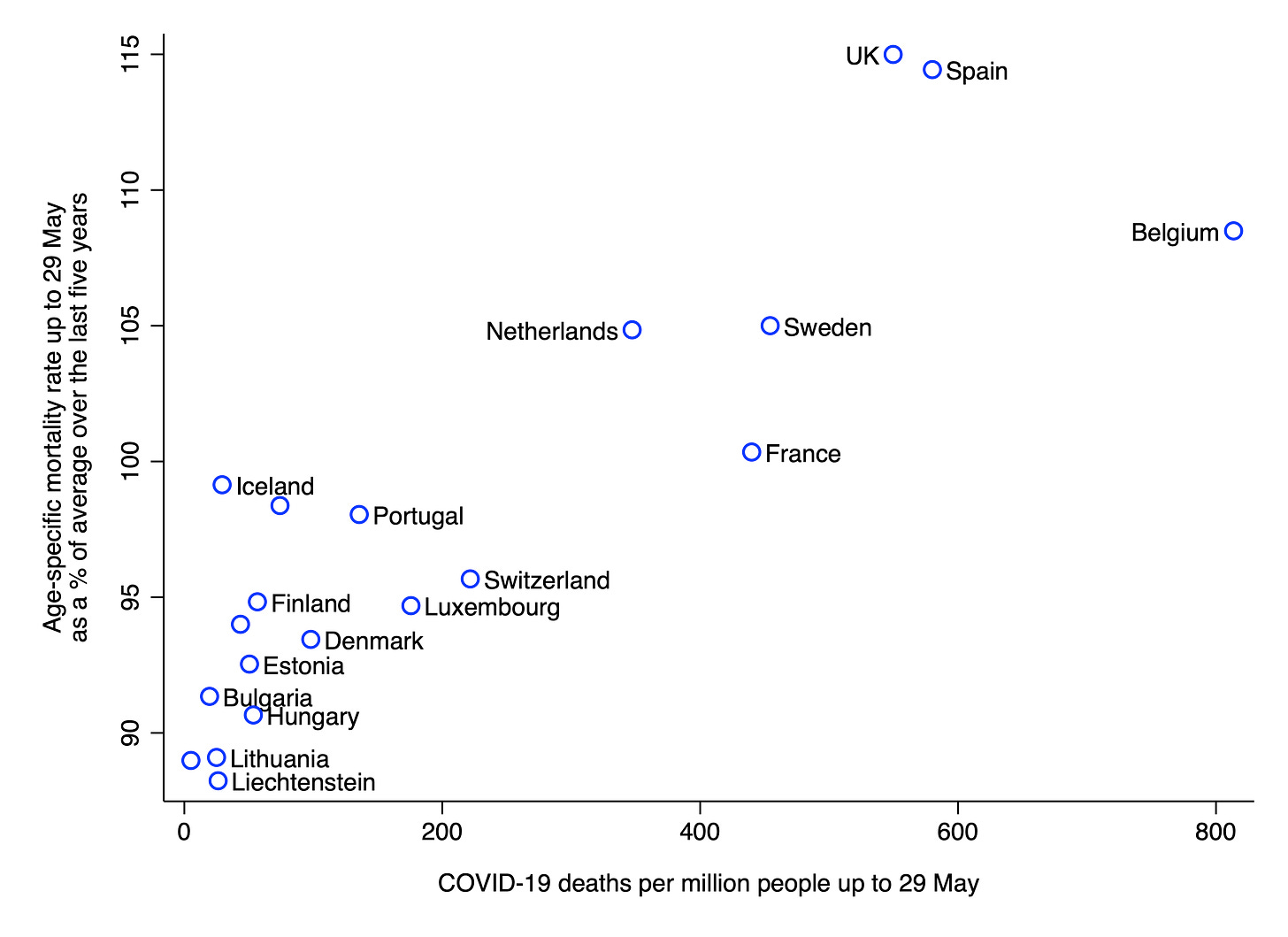

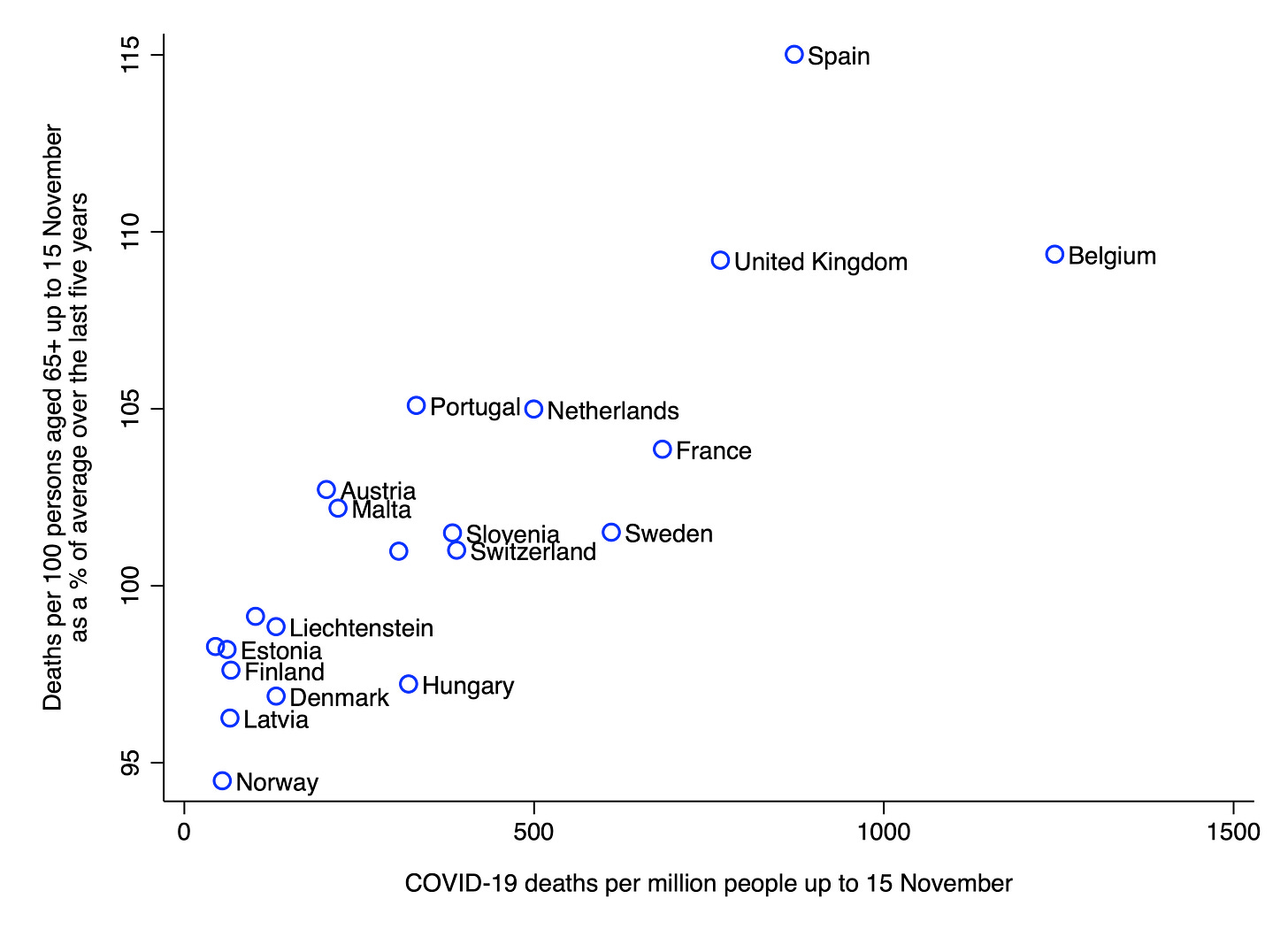

In order to examine the validity of COVID-19 deaths per capita, I obtained data on that measure, as well as two alternative measures of the disease’s lethality, for a number of European countries. The first alternative measure is the age-specific mortality rate (ASMR) up to 29 May as a percentage of the average over the last five years. And the second is deaths per 100 persons aged 65+ up to 15 November as a percentage of the average over the last five years. Both of these alternative measures attempt to quantify the age-adjusted excess mortality attributable to COVID-19.

Data on COVID-19 deaths per capita were taken from Our World in Data. Data on ASMRs were taken from the ONS. And data on deaths per 100 persons aged 65+ were taken from Eurostat. The cut-offs of 29 May and 15 November correspond to the limits of data availability for a reasonable large sample of countries. For further details about the two alternative measures, please see my previous newsletter.

The chart below shows the relationship between COVID-19 deaths per capita and the ASMR up to 29 May as a percentage of the average over the last five years. The relationship is very strong and positive (r = .87, p < 0.001). Countries with a high number of COVID-19 deaths per capita saw more excess mortality up to 29 May than those with a low number of COVID-19 deaths per capita.

The chart below shows the relationship between COVID-19 deaths per capita and deaths per 100 persons aged 65+ as a percentage of the average over the last five years. Once again, the relationship is very strong and positive (r = .84, p < 0.001). Countries with a high number of COVID-19 deaths per capita saw more excess mortality up to 15 November than those with a low number of COVID-19 deaths per capita.

These results indicate that COVID-19 deaths per capita has reasonably good validity as a measure of the disease’s lethality in Europe. In other words, the measure is not simply tracking cross-country differences in how COVID-19 deaths are counted. Of course, given the small sample of countries, and the fact that they are all in Europe, one should be cautious about generalising the results to other parts of the world. It is possible that the relationship between COVID-19 deaths per capita and age-adjusted excess mortality would break down if more countries were included in the analysis.

Image: Gustaf Rydberg, Vinterlandskap med hästfora, 1868

Is there an expert consensus on lockdowns?

Most Western countries have implemented lockdowns as a way to reduce the spread of COVID-19. And they have presumably done so on the basis of advice from scientific experts. Sweden, of course, is a notable exception. Anders Tegnell, the Swedish state epidemiologist, has been outspoken in his opposition to lockdowns. However, given that the Swedish exception appears to “prove the rule”, one would assume that there is an overwhelming expert consensus in favour of lockdowns.

In order to find out whether this is indeed the case, Daniele Fanelli carried out an expert survey. Using the Web of Science database, he identified 1,841 authors who had published at least one paper that included certain keywords relating to COVID-19 mitigation (e.g., ‘lockdown’ and ‘COVID-19’). He then emailed each of these authors the following question:

In light of current evidence, to what extent do you support a ‘focused protection’ policy against COVID-19, like that proposed in the Great Barrington Declaration?

86 of the emails went undelivered, leaving him with 1,755 potential respondents. So far, only 117 have responded (meaning that the current response rate is 6.7%). His latest results are nonetheless interesting and – to me – surprising. As of 27 December: 27% answered “none”, 18% answered “a little”, 28% answered “partially”, 15% answered “mostly”, and 12% answered “fully”. This means that 55% of those who responded were at least “partially” in favour of a focused protection strategy.

It is not clear what explains the disparity between the views of Fanelli’s respondents and the apparent views of most governments’ scientific advisors. One possibility is that Fanelli’s respondents are simply not representative of scientific experts. Due to the small sample, this certainly cannot be ruled out.

Another possibility is that many scientists who are against lockdowns have been afraid to speak out, due to fear of being labelled a “COVID denialist” or something similar. The Nobel Prize winner Michael Levitt, who has expressed opposition to lockdowns, was disinvited from a conference earlier this year because there were “too many calls by other speakers threatening to quit” if he attended.

A third possibility is that governments are actually getting a range of opinions (i.e., both pro- and anti-lockdown advice) but most have taken what they regard as the cautious approach of implementing lockdowns. This may be due to incentives that favour acting over not acting. For example, the costs of locking down are dispersed across society and may be spread out over several years, whereas the costs of not locking down are concentrated and immediate.

Incidentally, I am not making an argument for or against any particular strategy for dealing with COVID-19. I am simply trying to reconcile Fanelli’s results with the fact that most Western governments have decided to implement lockdowns.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.