NOTE: I now write for Aporia Magazine. Please sign up there!

In the debate over the causes of group differences in IQ, it is often claimed that no serious scientist believes genes play a significant role. The only people who believe this, it is said, are assorted cranks and amateurs.

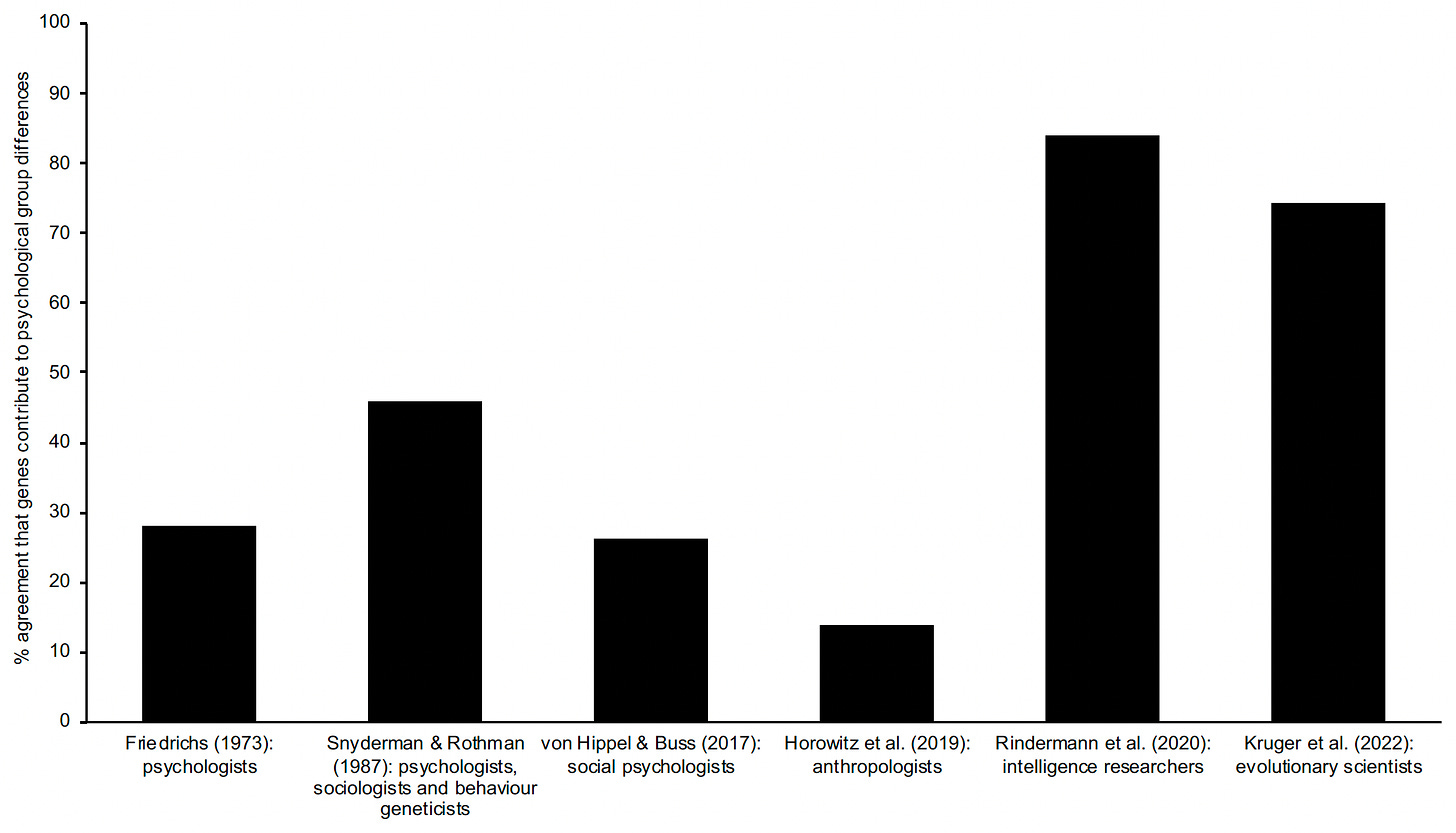

We can quickly dispense with this claim by consulting the various expert surveys that have been conducted over the years. Both Sean Last and Emil Kirkegaard have covered these before, but for several reasons I thought I do my own write-up: to correct a minor error in Sean’s post; to add results from the most recent study; and to present a summary chart showing all the results.

One of the earliest expert surveys was carried out by Friedrichs (1973). He asked members of the American Psychological Association to what extent they agreed with the following statement:

Arthur Jensen’s article, “How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?” in the Spring, 1969, HARVARD EDUCATIONAL REVIEW states that “it (is) a not unreasonable hypothesis that genetic factors are strongly implicated in the average Negro-white intelligence difference. The preponderance of the evidence is, in my opinion, less consistent with a strictly environmental hypothesis than with a genetic hypothesis”

Overall, 28% said “agree” or “tend to agree”, whereas 60% said “disagree or tend to disagree”. So a sizeable majority disagreed with the “Jensen thesis”, but a non-trivial fraction agreed. (Sean accidentally gave the percentage who “tend to agree” as 28%, rather than 18%. As a result, his percentages summed to more than 100.) The response rate was 65% and the number of respondents was 341.

The next major expert survey was carried out by Snyderman and Rothman (1987). They asked members of various professional societies, including the American Psychological Association and the Behavior Genetics Association, about the sources of the black-white IQ gap. 45% said the gap was a “product of both genetic and environmental variation”. 15% said it was “entirely due to environmental variation”. And 1% indicated belief in an “entirely genetic determination”.

So a sizeable plurality believed the black-white IQ gap is at least partly genetic, but another large fraction refused to answer or did not believe “there are sufficient data to support any reasonable opinion”. The response rate was 65% and the number of respondents was 661.

The next expert survey was carried out by Von Hippel & Buss (2017). They asked members of the Society of Experimental Social Psychology “how likely they thought it was that members of some ethnic groups were genetically more intelligent” than members of other ethnic groups. The average response was 26.4%, which is substantially less than half but substantially greater than zero. The response rate was 37% and the number of respondents was 335.

The next expert survey was carried out by Horowitz et al. (2019). They asked American academic anthropologists whether “the comparatively high IQ scores and disproportionate scientific contributions of Ashkenazi Jews … reflect in part a genetic component of their intelligence”. 14% agreed and 57% disagreed. So disagreement was almost three times more common, but agreement was still non-trivial.

Interestingly, when they broke down the answers by sub-specialty, they found that agreement was 21% among biological anthropologists but only 9% among cultural anthropologists. The response rate was 19% and the number of respondents was 301.

Horowtiz et al. also asked respondents whether “attempts to discover a genetic component to behavioral differences between “racial” groups are bound to fail”. In this case, 78% agreed and only 8% disagreed. However, this question is less informative as it uses the contested term “racial”, and because it conflates methodology with scientific truth (even if differences exists, attempts to discover them might still be bound to fail).

The next expert survey was carried out by Rindermann et al. (2020). They asked intelligence researchers about the causes of the black-white IQ gap. 84% said that it was at least 10% genetic, while 16% said that was 100% environmental. Hence the vast majority believed in some genetic contribution. However, the response was only 16% and the number of respondents was only 86.

The most recent expert survey was carried out by Kruger et al. (2022). They asked evolutionary scientists in the fields of psychology, anthropology and biology, “Are there population differences in psychology and behavior resulting from different ancestral ecologies and environments?” An overwhelming majority, 74.4%, said “yes”. Only 11.1% said “no”.

The question did not ask specifically about differences in IQ. Yet if there are general psychological differences “resulting from different ancestral ecologies and environments”, there is no reason why there can’t be differences in IQ. (Respondents were asked separately about sex differences.)

Another caveat is that the question could be interpreted to include differences “resulting from different ancestral ecologies and environments” passed down through culture. However, this is certainly not the natural interpretation, nor the one the authors intended (see their remarks on p. 4). The response rate was not reported, but the number of respondents was 581.

Having reviewed all the expert surveys since the 1970s, we can now plot the results in a chart, as shown below.

The percentage of experts who agree that genes contribute to psychological group differences ranges from 14% to 84%, with an average of 45%. The two most recent surveys yield the highest percentages. Note that if “don’t knows” were excluded, some of the percentages would be higher.

Overall then, a sizeable fraction of scientists working in relevant fields do believe that genes contribute to psychological group differences. Claims to the contrary are not based in evidence.

Image: Sybil Eysenck, Hans Eyesenck, German-born British psychologist

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

I'm sure the high non-response rate is mostly just a result of people not being interested in responding. But I also wonder how many people don't respond to these kind of studies because they don't want to offer any kind of opinion to a controversial question.