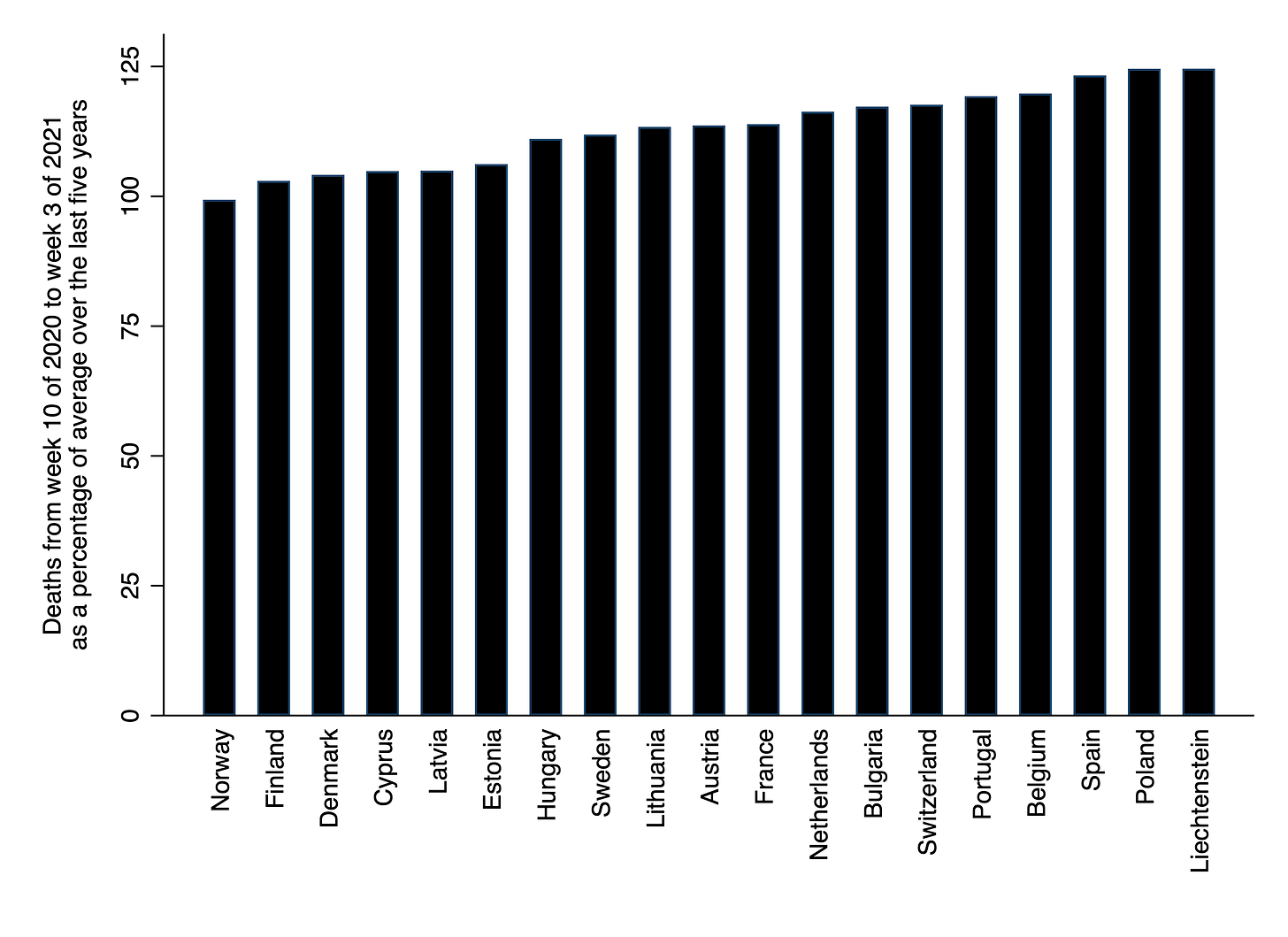

Excess mortality since the pandemic began

In a previous newsletter, I compared European countries on the number of excess deaths from week 10 to week 52 of 2020, per million people. However, this comparison was not entirely apples-to-apples, since some European countries reached the peak of their winter wave in December, whereas others reached the peak in January.

In order to make a “fairer” comparison, I computed excess deaths from week 10 of 2020 to week 3 of 2021. This calculation was slightly more complex than the previous one, since 2020 had a “week 53”, and there were also the first three weeks of 2021 to consider. To compute total deaths for 2019, I summed deaths between week 10 and week 52 of that year, and then added the values for weeks 1, 2, 3 and 52 again. Here, weeks 1, 2 and 3 correspond to the first three weeks of 2021, while week 52 corresponds to the fifty third week of 2020.

I did the same for 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015. The only difference was that, for 2015, the value for week 53 of that year was added, rather than the value for week 52. (The other years did not have a week 53.) I then computed excess deaths as total deaths from from week 10 of 2020 to week 3 of 2021 minus the average of total deaths in the years 2015–2019. Rather than dividing excess deaths by total population, I divided it by the the average of total deaths in the years 2015–2019. Hence I obtained excess mortality in percentage form. The resulting figures are shown below.

Due to reporting delays, data were only available for nineteen countries. Liechtenstein has the highest excess mortality, which may be partly due to its small population and hence greater susceptibility to random fluctuations in the number of deaths. As expected, Norway and Finland have the lowest excess mortality. Interestingly, Sweden is ranked 12 out of 19 countries, meaning that – of the countries examined here – only seven have lower excess mortality than Sweden. Among the missing countries are Italy, Czechia and the UK, which would almost certainly also have higher excess mortality than Sweden.

A comprehensive analysis of COVID-19’s lethality in different countries can only be made once the pandemic is over. However, the preliminary figures in the chart above suggest that Sweden was not hit substantially harder than other countries in Europe, despite its comparatively relaxed approach.

Image: Arnold Plagemann, Fartyg delvis med Nederländsk flagg, 1861

COVID-19 and the European Union

Douglas Murray wrote an interesting piece for the Mail on Sunday, criticising the EU’s handling of the pandemic. He draws a comparison with the Eurozone debt crisis, noting that in both cases, most countries put their own interests first, even though this had the effect of undermining European solidarity.

For example, Germany banned the export of PPE to Italy in the early months of the pandemic, while France insisted that the EU purchase millions of doses of its own vaccine, which has ended up being delayed. (A delay in France! Whatever next?) According to Murray:

The French blame the Germans and the Germans blame the French. The Eastern Europeans blame the Western Europeans. The Southern Europeans blame the North. And everyone blames the officials in Belgium. In other words, business as usual.

Coincidentally (or perhaps not), I came across a letter written in 1998 by the philosopher John Rawls, which now appears rather prescient:

It seems to me that much would be lost if the European union became a federal union like the United States … Isn’t there a conflict between a large free and open market comprising all of Europe and the individual nation-states, each with its separate political and social institutions, historical memories, and forms and traditions of social policy. Surely these are great value to the citizens of these countries and give meaning to their life.

Don’t mention the g-word

Gregory Clark is an economic historian who does fascinating work on the industrial revolution, social mobility, and social inequality. (He also likes to give his books titles that are puns on Ernest Hemingway novels. His last two were called ‘A Farewell to Alms’ and ‘The Son Also Rises’.) A few days ago, he got into a spot of bother at the University of Glasgow.

According to the student newspaper, Clark was due to deliver a seminar (I presume virtually) titled ‘For Whom the Bell Curve Tolls: A lineage of 400,000 individuals 1750-2020 shows genetics determines most social outcomes’ (notice the pun). However, the seminar was postponed “amid pressure from student groups”. It’s not entirely clear what happened, but some students were apparently telling people “to register and not attend in order to take up all available slots”. (I suppose this is about as transgressive as you can be during a pandemic.)

It’s also worth noting that the student journalist described Clark as a “eugenicist”. (You have to understand that, for student radicals, ‘eugenics’ just means “something I don't like that has to do with genetics”.) This reminded me of the Bret Stephens affair in December of 2019, during which the Guardian – a supposedly serious newspaper – ran an article titled ‘New York Times columnist accused of eugenics over piece on Jewish intelligence’.

In any case, Clark could probably have avoided the whole incident if he’d gone with a slightly more strategic title. Mentioning the g-word (‘genes’) in the context of social inequality always arouses suspicion, and if you put it as bluntly as “genetics determines most social outcomes” people are bound to get offended. Throw in a reference to The Bell Curve, and you’re almost asking to be cancelled.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.