Dorsey the disingenuous

Jack Dorsey has made a thread explaining his company’s decision to ban Trump from the platform. (In my last newsletter, I argued that Twitter should not have been able to ban Trump, a sentiment echoed by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel.) Dorsey’s thread is – shall we say – disingenuous. He portrays himself as a principled libertarian believer in internet freedoms, who reluctantly banned a single account in the face of imminent and catastrophic violence. What follows are Dorsey’s tweets, followed by my comments.

I believe this was the right decision for Twitter. We faced an extraordinary and untenable circumstance, forcing us to focus all of our actions on public safety. Offline harm as a result of online speech is demonstrably real, and what drives our policy and enforcement above all.

The tweets that got Trump banned – which I’m not endorsing – were as follows. One said: “The 75,000,000 great American Patriots who voted for me, AMERICA FIRST, and MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, will have a GIANT VOICE long into the future. They will not be disrespected or treated unfairly in any way, shape or form!!!”. And the other said: “To all of those who have asked, I will not be going to the Inauguration on January 20th”. It is difficult to see how these tweets amounted to “an extraordinary and untenable circumstance”. (Twitter’s stated justification is not very convincing.)

In his tweet above, Dorsey notes that, “Offline harm as a result of online speech is demonstrably real, and what drives our policy and enforcement above all.” Again, this seems very difficult to believe. As others have pointed out, there are numerous examples of tweets from non-right-wing accounts which have contributed to “offline harm”, but which Twitter has made no attempt to censor: tweets calling for Trump to be killed; tweets encouraging rioting and looting; tweets calling for nation states to be “eradicated” etc.

That said, having to ban an account has real and significant ramifications. While there are clear and obvious exceptions, I feel a ban is a failure of ours ultimately to promote healthy conversation. And a time for us to reflect on our operations and the environment around us.

This reads like Trump was the first person to ever be banned from Twitter. In reality, Twitter has expunged many high-profile accounts, some based on standards that – if applied consistently – would have resulted in many more left-wing accounts being censored. And since the Capitol Hill riot last Wednesday, Twitter has purged thousands of accounts spreading the QAnon conspiracy theory. I am obviously not endorsing QAnon – which is completely absurd – but you may have noticed that a lot of Twitter accounts spread absurd claims without being censored.

This moment in time might call for this dynamic, but over the long term it will be destructive to the noble purpose and ideals of the open internet. A company making a business decision to moderate itself is different from a government removing access, yet can feel much the same.

Here Dorsey is commenting on the co-ordinated effort by Amazon, Google and Apple to remove Parler – the Twitter rival – from the internet (even though the Capitol Hill riot was organised in large part on Facebook). According to Dorsey, “a business decision to moderate itself is different from a government removing access”. Yes, it is different, and in this context it is worse. While there are many circumstances in which one would rather be served by private businesses than by the government, the digital public square is – at the present time – not one of them.

In the remainder of the thread, Dorsey says, “We can’t erode a free and open global internet”, and talks about much passion he has for Bitcoin. (Even though Bitcoin was designed in such a way, as he himself notes, that it cannot be “controlled or influenced by any single individual”). It’s hard to imagine what could do more to erode a “free and open global internet” than much of it being under the control of four or five giant companies steeped in the same corporatist-progressive culture.

Image: Axel Fahlcrantz, Skymning

Two open letters

Earlier this month, Professor Kathleen Stock – a “gender critical” feminist philosopher – was targeted by a scurrilous open letter signed by over 700 academics. (For those who aren’t up to date with the latest jargon, “gender critical” feminists are those who tend to believe that biological sex is immutable.) The document is titled ‘Open Letter Concerning Transphobia in Philosophy’. It mentions “harm” four times, and implies that Stock is someone who uses her “academic status to further gender oppression”.

Encouragingly, some other academics got together and penned a counter-petition, which has now been signed by over 400 people. They point out that the original letter – which unsurprisingly mischaracterised Stock’s views – will only serve to stifle academic debate about sex and gender. (Most people don’t like being the subject of moralistic denunciations endorsed by hundreds of their colleagues.) The denounced has written about the incident for The Spectator. She notes:

The authors of this letter clearly believed they could see into my soul – perhaps even without actually reading my views. Amusingly, the authors of the letter were later forced to add a correction to their claim that I am best known ‘for opposition to the UK Gender Recognition Act’ (In reality, I have no objection to the existence of the Act, and have objected to proposed reforms to it in favour of gender identity).

If you’re an academic philosopher in good standing, I would encourage you to sign the counter-petition (regardless of whether you agree with Stock’s views).

Excess mortality in Europe

Because most Western populations are ageing, the absolute number of people at risk of dying each year is going up. As a result, even if the age-specific death rates remain constant, the absolute number of deaths will increase from one year to the next. It is therefore important to adjust for age-structure when calculating excess mortality. In a previous newsletter, I noted that excess mortality in England (during the first 11 months of 2020) is 44% lower using age-standardised mortality rates.

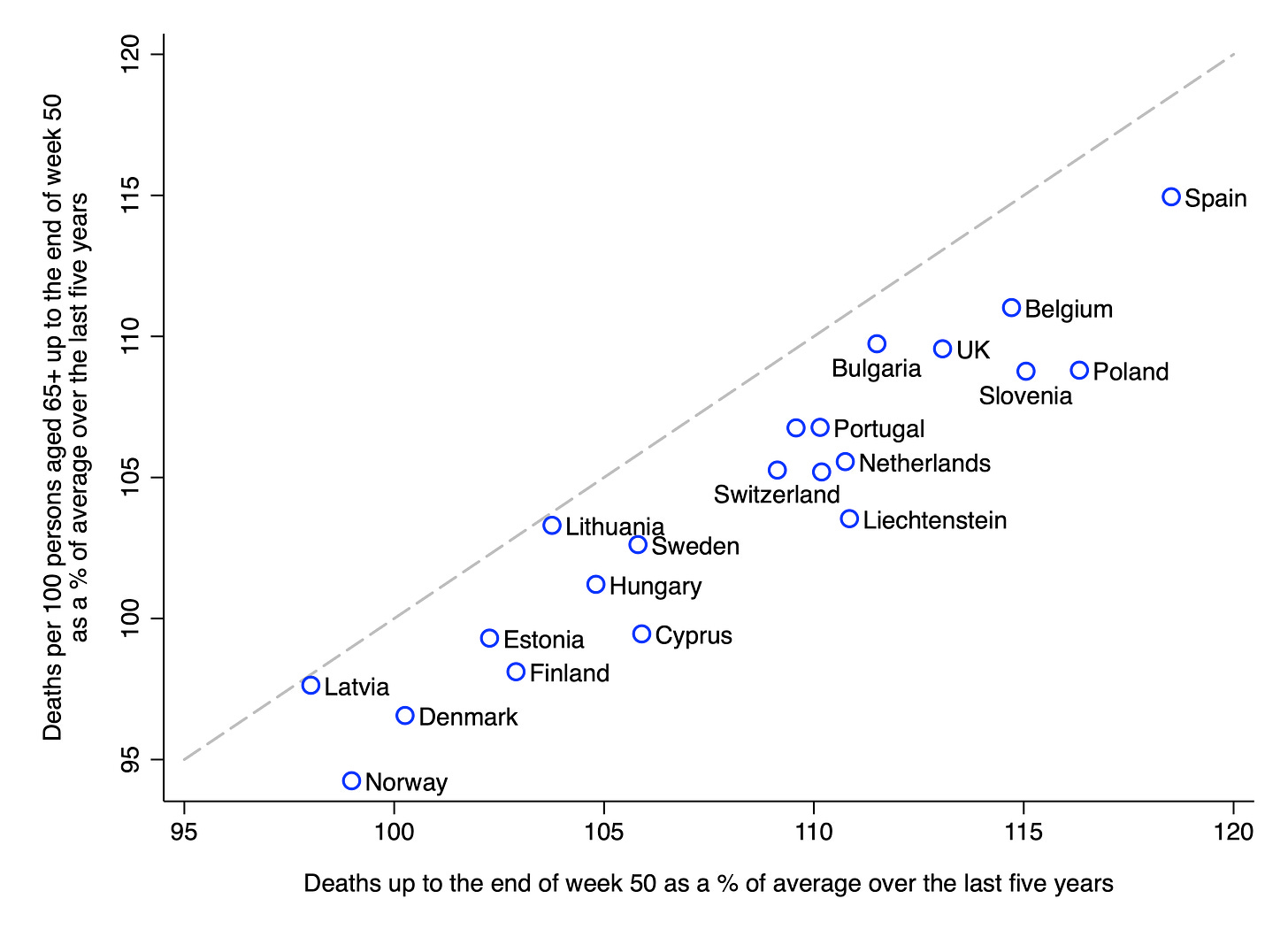

In order to carry out a similar exercise for other European countries, I obtained weekly data on the number of deaths, and yearly data on the number of persons aged 65+, from Eurostat. I then computed two measures of excess mortality: first, the number of deaths in the first 50 weeks of the year as a percentage of the average over the last five years; and second, the number of deaths in the first 50 weeks of the year per 100 persons aged 65+ as a percentage of the average over the last five years. The relationship between these two measures is shown in the chart below.

The dashed grey line is y = x. All 21 countries for which data were available fall below this line, which indicates that excess mortality is consistently lower after adjusting for age-structure. On average across the 21 countries, it is 8.2% before adjusting for age-structure and 4.2% after doing so. The latter figure is 49% less than the former. Of course, the overall relationship is strong and positive (r = .94), which indicates that adjusting for age-structure does not have much effect on the relative positions of the countries in respect of excess mortality.

As usual, this is not meant to imply that we shouldn’t be concerned about the COVID-19 pandemic, but only that we should compute excess mortality in the right way. Note that the 2019 value for number of persons aged 65+ was used for 2020 because the 2020 value is not yet available. And week 50 was chosen as the cut-off, rather than week 52, to allow for some reporting delays. (The figure of 4.2% should only be considered a very rough estimate of excess mortality.)

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.