COVID-19's impact on mortality has been small relative to pre-existing differences within Europe

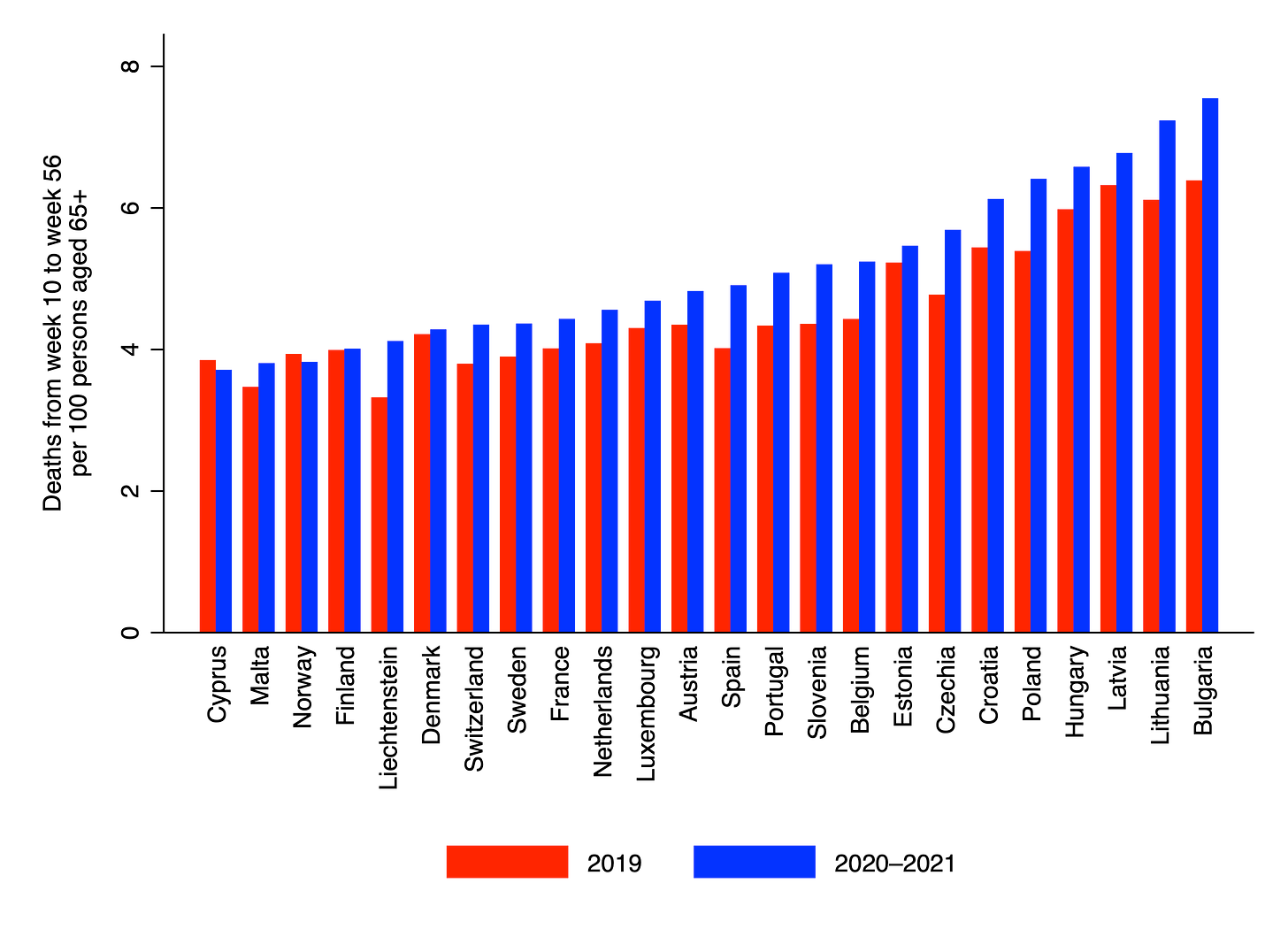

Consider the chart below, which compares deaths from week 10 of 2020 to week 3 of 2021 to deaths over the same period in the previous year. (Rather than taking deaths from week 10 of 2019 to week 3 of 2020, I added the deaths for weeks 1–3 from 2019 to the total for weeks 10–52. I also added deaths in week 52 again because 2020 had 53 weeks. This was done to allow for an ongoing comparison between 2020–21 and the previous year. I stopped in week 3 of 2021 to allow for reporting delays.) Both totals were divided by the number of persons aged 65+ alive in January of the relevant year, so as to obtain age-adjusted death rates.

There are several things to notice in the chart. First, nearly all countries saw death rates increase from 2019 to 2020–21; the only two that didn’t were Cyprus and Norway. The largest increase was in Bulgaria, where the death rate went from 6.4 to 7.6 per 100 persons aged 65+, an increase of 1.2. (Interestingly, the rise in Sweden was less than half as big.) Second, there was considerable cross-country variation even before the pandemic hit. In 2019, Bulgaria’s death rate was 6.4 per 100 persons aged 65+, compared to only 3.5 in Malta – a difference of 2.9. (The difference between Bulgaria and Liechtenstein was even greater.)

This means that, in the year before the pandemic hit, the range of death rates within the EU was larger than the largest increase that any EU country (pictured here) has seen during the pandemic so far. In fact, the range of death rates in 2019 was more than twice as large as the largest increase from 2019 to 2020–21. Consider Belgium, which has reported one of the highest rates of confirmed COVID-19 deaths in Europe. Its death rate in 2020–21 was still lower than the pre-pandemic death rates in Poland, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia and Bulgaria.

One could make the same observation about different regions of the UK. Life expectancy prior to the pandemic was 80.8 in South East England, compared to only 77.2 in Scotland – a difference of 3.6 years. By contrast, I estimated that the UK’s overall life expectancy was 1.3 years lower in 2020 than in 2019. (Other researchers have reported similar figures.) Of course, the peak of the second wave occurred in January of 2021, so 1.3 years may be an underestimate of the pandemic’s total impact. But even if the true figure were as high as 1.6 years, this would still be much less than the difference in life expectancy between Scotland and South East England.

It is noteworthy that the high death rates in some countries and regions within Europe never prompted governments to take the sort of dramatic measures we’ve seen during the pandemic. (Incidentally, I’m not suggesting that lockdowns would have been an effective way to reduce them; just that they were never seen to justify a massive public health response.) Nor did those death rates ever attract sustained attention from the media. For example, Sweden’s experience with COVID-19 has been described as a “tragedy”, but to my knowledge this term is not frequently used to describe the situation in Eastern Europe or Scotland, where death rates are consistently higher than Sweden’s were in 2020–21.

I suspect there are several reasons for this. The first is that deaths from COVID-19 are seen to justify stronger government intervention than deaths from other causes since they can be more easily attributed to other people’s behaviour. As the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill argued, “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

A second reason is that we are probably more sensitive to changes than to stable differences – even if the differences are actually greater in magnitude. For example, Scotland’s mortality rate has been higher than South East England’s for many years, so it doesn’t register any more. But for the UK, 2020 saw the the largest one-year rise in mortality since the 1940s, which is hard not to notice.

A third reason is that many people expected the pandemic to be much deadlier than it has turned out to be. Early fears that up to, say, 0.8% of the population could end up dying have not come to pass – at least not in Europe. (Note that 80% prevalence times 1% mortality equates to 0.8% of the population dying.) This is partly thanks to the arrival of highly effective vaccines – something that was not taken for granted at the start of the pandemic.

COVID-19 triggered an unprecedented reaction from governments, though its impact on mortality so far has been small relative to pre-existing differences within Europe. There are several reasons for this: governments take Mill’s harm principle seriously; we are more sensitive to changes than to stable differences; and the pandemic has been less deadly than many people were expecting. An important caveat is that the pandemic is not yet over. But one hopes that a combination of vaccines and seasonal change will prevent large numbers of additional deaths over the coming months.

Image: August Behrendsen, Evening in the mountains, 1843

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.