COVID-19 deaths per capita understates mortality outside Europe

I’ve noted previously that confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people (as reported in various country “league tables”) has reasonably good validity as a measure of the disease’s lethality in Europe. But is it valid for comparisons outside Europe? Since European countries tend to be rich, they can afford to do lots of testing. But the same may not be true of countries in other parts of the world. As a consequence, there may be more false negative in non-European countries – i.e., deaths from COVID-19 that are not recorded in official statistics.

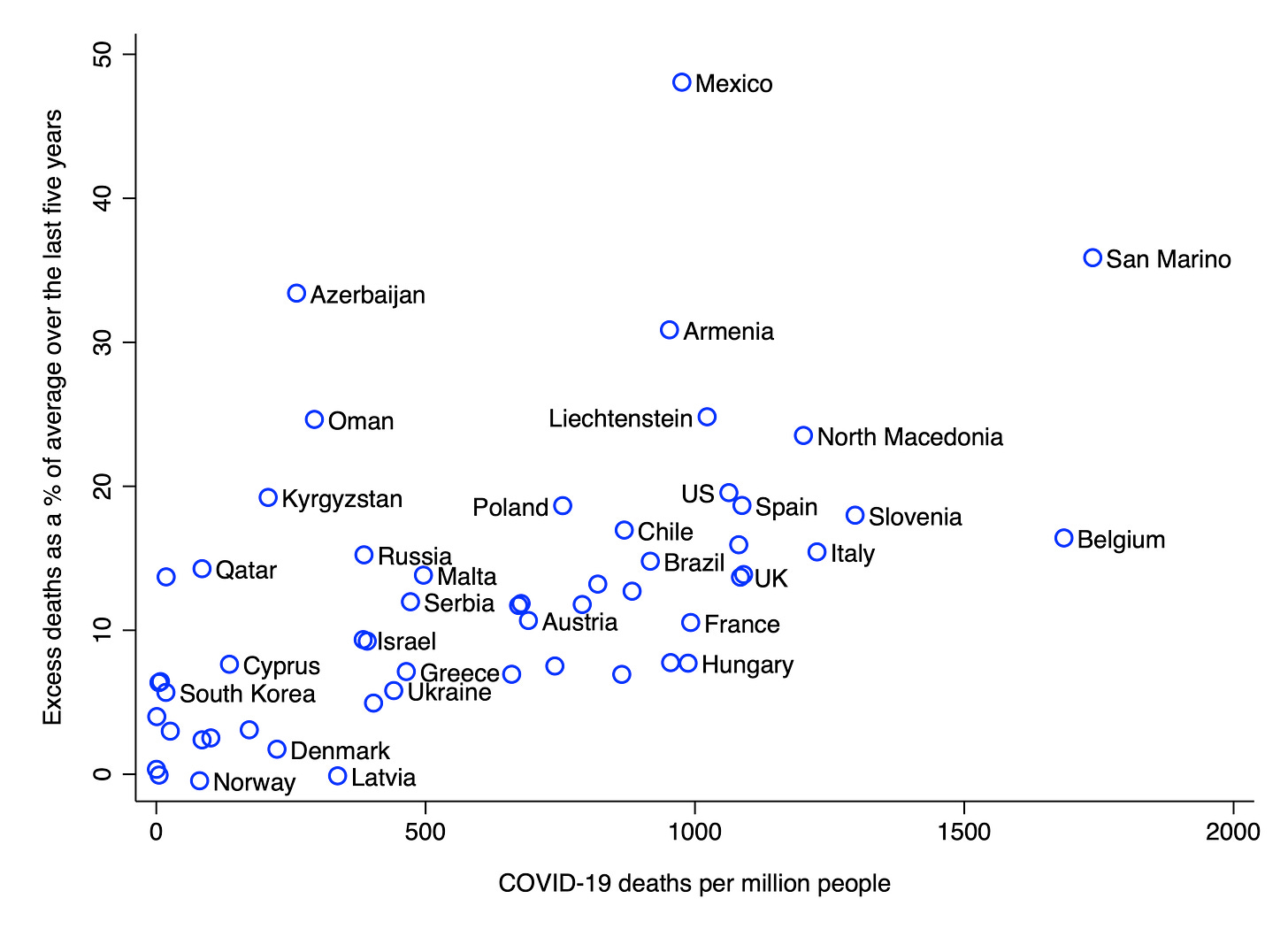

In a previous newsletter, I mentioned a few pieces of evidence suggesting that reported numbers of COVID-19 deaths may substantially understate actual numbers in poorer countries. Here I want to examine that possibility somewhat more systematically. I obtained data on confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people up to 31 December 2020, as well as excess mortality in 2020, from Our World in Data. (The latter is defined as deaths in 2020 as a percentage of the average over the last five years. Data were available for 55 countries.) The relationship between the two measures is shown in the chart below:

Overall, there is a moderately strong positive correlation between the two measures (r = .55, p < 0.001), indicating that COVID-19 deaths per capita has moderately good validity as a measure of the disease’s lethality. Notice that Azerbaijan, and to a lesser extent Armenia, have higher excess mortality than would be expected on the basis of their reported COVID-19 death rates. This may be because the two countries fought a small war in 2020. (According to Wikipedia, there were several thousand deaths on each side, which would be enough to affect excess mortality numbers).

After excluding Azerbaijan and Armenia from the analysis, the correlation between excess mortality and COVID-19 deaths per capita increased to r = .61. Regardless of whether these two countries are included, most of those situated in the upper left of the chart are non-European, whereas all those situated in the lower right are European. Mexico, in particular, has much higher excess mortality than would be expected on the basis of its reported COVID-19 death rate. (This may be partly attributable to the fact that 2020 was a deadlier-than-average year in the country’s ongoing drug war.)

Looking at COVID-19 deaths per capita, the five hardest-hit countries in this dataset are: San Marino, Belgium, Slovenia, Italy, and North Macedonia. However, looking at excess mortality, the five hardest-hit countries (excluding Azerbaijan and Armenia) are: Mexico, San Marino, Liechtenstein, Oman, and North Macedonia. Interestingly, Belgium falls from second place to twelfth place when switching between the two measures.

This analysis is obviously limited by the current lack of data on excess mortality for most non-European countries. (More data will presumably become available in due course.) Another limitation, as I’ve mentioned frequently in this newsletter, is that excess mortality does not take account of population ageing. But putting these considerations aside, the pandemic has probably had a much greater impact outside Europe than official numbers suggest.

Image: Ivan Shishkin, The Clearing, 1878

Counting COVID-19 deaths in England

Speaking of different ways to count COVID-19 deaths, it’s worth reexamining the situation in England and Wales. During the month of February, there were 20,004 deaths with COVID-19 on the death certificate, but only 11,663 excess deaths. (And recall that excess deaths may be an overestimate of the true figure.) This means either one of two things: many of the deaths with COVID-19 on the death certificate are false positives; or many fewer Britons than usual are dying of other causes. Of the two, the former seems much more likely.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.