Can experts gauge pandemic preparedness?

I recently polled my Twitter followers, and asked them whether the events of 2020 had made them more or less confident in “experts” (defined as people who are deemed, based on credentials or appointments, to have a high level of knowledge in a specific domain). Of the 577 people who responded, 83% said “Less confident”, and only 5% said “More confident”. (The remainder said “No change”.)

Many of last year’s expert follies are catalogued in this excellent piece for UnHerd by Jacob Siegel. Perhaps the most absurd was when, after months of lecturing the public about the importance of social distancing, around 1,200 public health “experts” signed an open letter supporting the Black Lives Matter protests on the grounds that “White supremacy is a lethal public health issue that predates and contributes to COVID-19”. (It’s hard to know where to begin with that one.)

In the context of a global pandemic, one characteristic you’d hope experts might have is the ability to gauge which countries were well-prepared and which weren’t. Of interest in this regard is the Global Health Security Index, developed by researchers at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, and the Economist Intelligence Unit. According to the website, “The GHS Index seeks to illuminate preparedness and capacity gaps to increase both political will and financing to fill them at the national and international levels.”

It is based on 140 questions, which are organised into six major categories: Prevention; Detection and Reporting; Rapid Response; Health System; Compliance with International Norms; and Risk Environment. Each country is assigned an overall score, with higher scores indicating greater preparedness. In 2019, the highest score was achieved by… the United States. And the second highest score was achieved by the United Kingdom. The lowest ranked country, at 195, was Equatorial Guinea.

China, you’ll be interested to learn, was ranked 51 with an above-average score on the index. China also received an above-average score in the category “Prevention of the emergence or release of pathogens”. (Some of the countries ranked below China in this category include Israel, Lithuania, Liechtenstein, Iceland and Malta.) Perhaps next year, they’ll be bumped down a rank or two.

Based on current data from the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be fair to say that the most “successful” countries include: Singapore, South Korea, Japan, New Zealand, Australia and Norway. How did these countries fare on the GHS index? Australia was ranked 4; South Korea was ranked 9; Norway was ranked 16; Japan was ranked 21; Singapore was ranked 24; and New Zealand was ranked 35. Several of these countries have geographical advantages over places like Britain and the US, but Singapore’s placement of 24 seems particularly unfair. (If your index has anything to do with state capacity, a good rule of thumb is just to place Singapore at the top.)

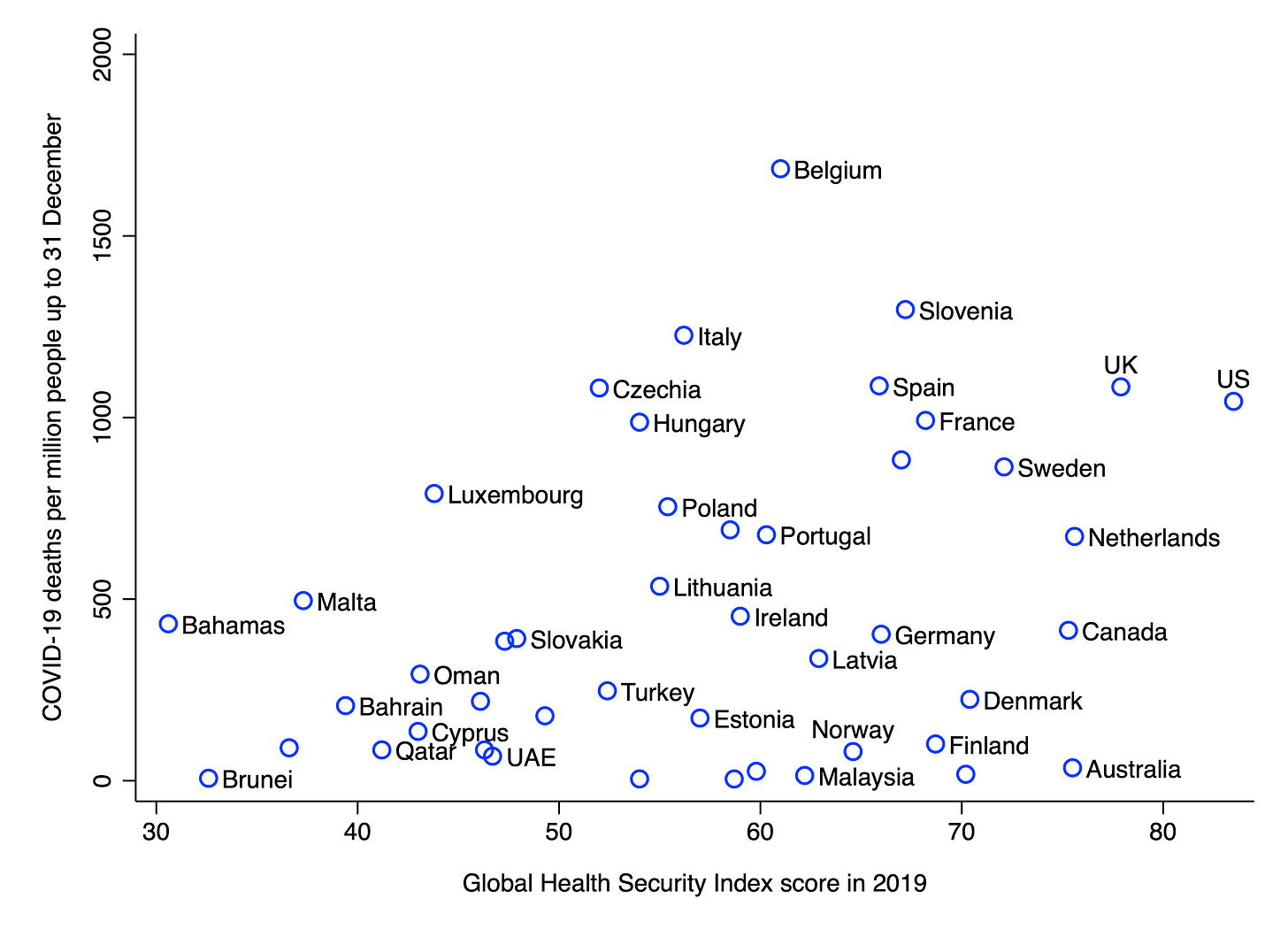

In order to examine the relationship between the GHS index and COVID-19 death rate, I obtained data on COVID-19 deaths per million people up to 31 December from Our World in Data. As in my previous newsletter, I restricted the sample to countries with GDP per capita > $25,000. This was done in order to compare countries with the greatest capacity to deal with pandemics, and to exclude those that may have underreported deaths from COVID-19. (No GHS index score was available for Taiwan.) The scatterplot is shown below.

There is no evidence of a negative relationship. In fact, the correlation is positive and significant (r = .33, p = 0.027, n = 46). Countries with higher GHS index scores have seen more deaths from COVID-19 per million people. Of course, this may be partly due to factors such as geography and age-structure, and I’m obviously not claiming this is a comprehensive analysis. The point is merely that the GHS Index doesn’t seem to track “success” in dealing with the pandemic.

One area in which experts have earned their stripes in recent months is vaccine development. And to the extent that several of the approved vaccines were developed in Britain or the US, those two countries may deserve somewhat higher rankings on the GHS index than their COVID-19 outcomes would appear to justify. Overall, however, the GHS index seems like another case of expert fallibility.

Image: William Keith, California Ranch, 1908

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.