NOTE: I now write for Aporia Magazine. Please sign up there!

In his infamous 2021 article ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, Vladimir Putin wrote that he “firmly believes” Russians and Ukrainians are “one people – a single whole”. After a year of fighting in which Ukraine’s armed forces have put up fiercer resistance than even their Western backers had anticipated, this statement looks nothing short of delusional.

Yet many Western commentators appear to be engaged in the very same fallacy – of lumping all Ukrainians together.

There’s a popular narrative that goes something like this. In 2014, Ukrainians rose up and toppled their corrupt president, who was little more than a puppet controlled by Moscow. After this “Revolution of Dignity”, they set out on a path to join the West. Yet their aspirations were thwarted when Putin annexed Crimea and brainwashed hapless Russian speakers in the Donbas into rebelling, thereby plunging that region into civil war.

So apart from a tiny minority of Russian speakers who were being fed a constant stream of pro-Kremlin propaganda, Ukraine wants to be part of the West. Here are some examples taken from Western media outlets and academic blogs; they’re all from 2021 or earlier.

Now, we all use countries’ proper names as a shorthand when referring to the goals of their governments, or the desires of a majority of their citizens. I do it all the time. Saying “Russia wants to achieve X” is much more convenient than saying “Vladimir Putin, a large part of the security apparatus, and a certain percentage of citizens want to achieve X”.

Yet when talking about a country like Ukraine (or Northern Ireland, or any other place with strong ethnic divisions) we have to be particularly careful. In 2016, the largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly and the first minister herself supported Brexit. Yet in Northern Ireland as a whole, a majority voted Remain. So did Northern Ireland want to leave the EU? It’s not a useful way of phrasing the question.

With that in mind, let’s examine the popular narrative about Ukraine.

Is it true that Ukrainians rose up and toppled their president? No one would dispute that there was widespread support for the Euromaidan movement. Yet there was also widespread opposition – particularly in the Donbas and Crimea. Here’s what two scholars wrote in the Washington Post ten days before Yanukovych was ousted:

Surveys taken in the past two months in the country as a whole range both in quality and in results, but none show a significant majority of the population supporting the protest movement and several show a majority opposed … there is little evidence that a clear majority of Ukrainians support integration into the European Union.

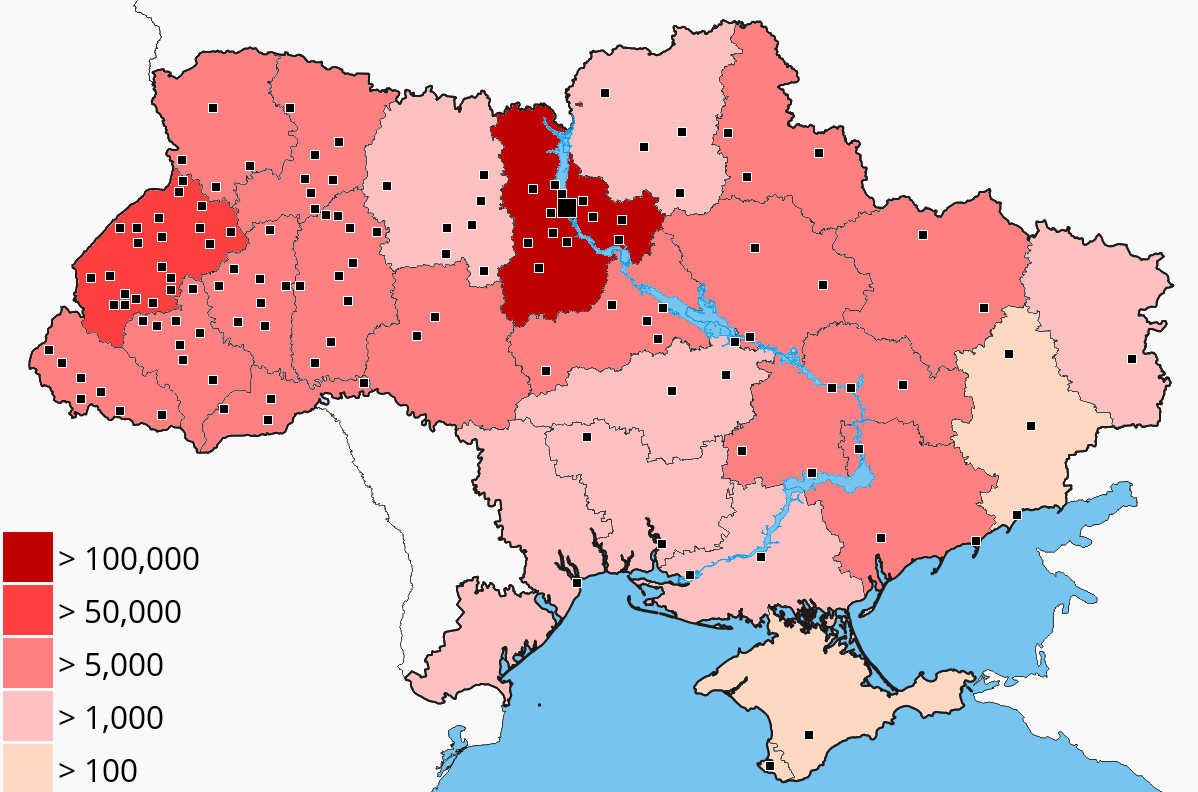

Here’s a map of the Euromaidan protests, where colour corresponds to the peak number of attendees. As you can see, they were overwhelmingly concentrated in the west of the country and around Kiev. Neither Crimea nor Donetsk had even a single protest with more than 1,000 attendees.

The map is consistent with results of both the 2004 and 2010 elections, where a clear majority of people in the east of Ukraine supported the more Russian-friendly party, while a clear majority of people in the west of Ukraine supported the more Western-friendly party.

It is also consistent with a recent poll which found that 21% of people in the west have lost a loved one in the war, compared to “only” 14% in the east and 12% in the south. The higher figure for the west suggests that more men from that part of the country have volunteered to fight, even though most of the fighting has taken place in the east and south.

Public opinion did shift toward the west after the “Revolution of Dignity”, but that was partly because Crimea and the densely populated areas of Donetsk and Luhansk – the most pro-Russian parts of the country – were no longer represented. Indeed, a Pew Research survey in Crimea shortly after the referendum found that 88% of respondents said “Kyiv should recognise the results”.

Another reason public opinion shifted was that Yanukovych’s government, and by extension the Russian-friendly Party of Regions, had been delegitimised by the massacre of protestors on the Maidan. Yet there’s overwhelming evidence that this massacre was a false flag operation carried out by the Ukrainian far-right. I’m not going to get into the evidence here, but I’d strongly recommend reading this paper and watching this interview with Ivan Katchinovski – the Ukrainian-born scholar who’s put it all together.

What about the Donbas? Were the people who protested against the new government simply brainwashed by Russian propaganda? Not according to researchers from the RAND corporation. In a comprehensive report titled ‘Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine’, they write:

The Rada voted to repeal the official status of the Russian language on February 23, stoking fear and anger in the east … The protesters portrayed their actions as spontaneous and self-initiated, driven by public anxiety about the future after the victory of the Maidan movement … Russian intelligence may have played a role in fomenting discontent, but the public agitation and outcry appeared genuine and not disconnected from the country’s political divisions.

Russia did carry out an “information campaign” to gin up support for the separatists, but it “remained a sideshow throughout the conflict”, having proved “more successful at agitating the West than at delivering tangible results”. This is not to say that everyone in the Donbas supported separatism; far from it – just that support for separatism was sizeable and, in large part, homegrown. Here’s a picture of a pro-Russian rally:

The “fear and anger” felt by ethnic Russians in the Donbas was not without justification either. Although the Rada’s vote to “repeal the official status of the Russian language” was vetoed by the acting president, it was an extremely divisive move given the circumstances. And laws restricting use of the Russian language were subsequently introduced.

In 2015, the Rada passed controversial “decommunization” laws, which mandated the removal of communist-era monuments and place names, and made it a criminal offence to deny the legitimacy of “the struggle for the independence of Ukraine”. (I presume that Putin’s stated goal of “denazification” was a reference to these laws.)

As evidence of how controversial they were, a group of leading scholars wrote an open letter to Ukraine’s president calling for them not to be adopted. These scholars argued that the laws violated freedom of speech, gave “support to those who seek to enfeeble and divide Ukraine”, and made it a crime to question the legitimacy of organisations that “collaborated with Nazi Germany”.

One could also mention the Odessa massacre, and the atrocities carried out by far-right paramilitaries in the Donbas – which have been documented by the UN, the OSCE and Human Rights Watch. (Separatist paramilitaries also committed atrocities, it should be noted.)

By saying all this, I’m certainly not taking Russia’s “side”. The official Russian government narrative has just many – if not more – holes than the popular Western narrative. (Perhaps the biggest hole is the idea that support for separatism extends far beyond the Donbas and Crimea.) And whatever grievances ethnic Russians may have, they obviously don’t justify Putin’s brutal invasion.

My point is this. Ukraine has long been an ethnically divided country. We have always supported one particular faction – the Western-leaning one. In 2014, war broke out following what can most charitably be described as a highly irregular change of government. (Some would say “Western-backed coup”.) Since then, we have continued to support the Western-leaning faction, and today Western weapons are being used against pro-Russian Ukrainians.

For its part, Russia has pursued an even more one-sided policy – completing disregarding the views Ukrainians that don’t want to be part of Russia, and in fact raining missiles down on their cities.

If I were Russian, I’d be focussing my criticism on Russia. (Well, maybe I wouldn’t, as I might wind up in jail.) But I’m a Westerner, so I’ll focus my criticism on the West. It is highly disingenuous to claim we have been supporting “Ukraine”, unless that term is taken to mean “the post-Maidan governments of Ukraine”. What we’ve been doing is supporting the Western-leaning faction of an ethnically divided country.

I think it’s fair to say that the faction we’ve been supporting is larger – at this point much larger. It’s also the one represented by Ukraine’s current government. But the fact remains: a substantial minority of Ukrainians in what we recognise as Ukrainian territory (i.e., Crimea and the Donbas) do not want to be part of the West. And we’re acting against their interests.

This fact does not imply we should give Putin everything he wants; that would be absurd. But it arguably does strengthen the case for negotiations. At the very least, it calls for more careful use of language.

Image: War in Donbas, 2015

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

Well said.

I come from Eastern Europe, and distrust of Russia is in my genes. The Russians have been an Imperialist power, advancing toward the west and the south, for well over three centuries now. Sometimes they are pushed back, but eventually the resume their onward march.

I especially am opposed to the current Russian campaign of bombing open cities, massacring civilians, making war on civil society, and so on.

But everyone in Eastern Europe knows that current Ukraine is an amalgam of two very different peoples. In the western portion, they are Uniate (Greek Catholic), and in tune with (most) Western values. In the East, they are Greek Orthodox, and look to Russia for their culture and civilization. The rift goes back at least as far as the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, which included the western, but not the eastern, parts.

Even western Ukraine is not homogenous. Chernivtsi Oblast has a significant Romanian ethnic minority, as has Izmail Raion (part of Odessa Oblast). Both regions were gained from Romania by the Ukrainian SSR as a result of the Molotov-von Ribbentrop pact of 1940. But the history involves both the Austrian and Russian Empires at various times. Eastern European history is complicated and can be used to justify any number of geographic arrangements.

I believe all of this, but it is weird I haven't seen any viral post or interview of a Ukrainian expressing a skeptical view about their country and the West's strategy.