Are South Asians more susceptible to Covid?

Blacks and South Asians living in Britain have higher rates of death from Covid than the white majority. These disparities received a lot of attention at the start of the pandemic, but have since garnered much less interest. It was initially assumed they were explained entirely by socioeconomic factors, such as geography, household structure, occupation and deprivation. However, as I argued back in May of last year, evidence suggests that socioeconomic factors are not sufficient to explain non-white Britons’ elevated Covid death rates.

Here I want to revisit the question of whether South Asians, specifically, are more susceptible to Covid than white Britons. By this I mean: are they biologically predisposed to higher death rates – either because they’re more likely to become infected conditional on exposure, or because they’re more likely to die conditional on infection (or some combination of the two)? Incidentally, I’m focussing on South Asians simply to reduce the amount of literature I need to cover. Since blacks and South Asians represent different races – excuse me, “ancestral populations” – it’s not unreasonable to consider them separately.

Let me deal with one objection right off the bat. Isn’t exploring the biological basis of ethnic disparities in Covid outcomes an example of that extremely sinister thing known as “race science”? By even suggesting that biology might play a role, aren’t I basically calling for the reestablishment of the Third Reich? After all, only an ignorant and racist person like Sir Ronald Fisher would claim that ethnic groups aren’t 100% biologically identical, right? Wrong. Whether genes contribute to group differences in Covid outcomes is a purely scientific question; it has no necessary implications.

As a matter of fact, the government’s own Race Disparity Unit noted in a recent report on Covid inequalities that there is “some evidence to suggest that genetic differences may play a role for some ethnic groups”. This should assuage any fears that you’re about to go down the rabbit hole into a world of black uniforms, torch-lit marches and Blitzkriegs across Europe. (Of course, it’s also consistent with the truly terrifying possibility that the people running the country are nothing more than a cabal of race scientists trying to advance their insidious agenda of understanding the biological basis of Covid susceptibility.)

Several studies have looked at whether ethnic disparities in Covid outcomes disappear when you control for socio-economic factors. The UK’s Office for National Statistics has carried out two such analyses: one for the first wave, and one for the second. Their results corresponding to the first wave are shown below. The fully-adjusted model controlled for geography, type of residence, household composition, occupation, deprivation and certain preexisting health conditions. When adjusting for all these factors, South Asian men had higher rates of Covid deaths, but Bangladeshi and Pakistani women did not.

This seems to suggest that biological differences in Covid susceptibility are unlikely. However, there are a couple of things to bear in mind. Covid deaths were undercounted in the first wave, due to lack of testing, which may have led to wrong estimates. In their analysis of the second wave, the ONS found larger ethnic disparities that did remain significant in the fully-adjusted model. In addition, several of the pre-existing health conditions that were included in their models may be more common among South Asians for partly biological reasons. Hence the total effect of biological variables may exceed that of the blue bars in the chart above.

In a separate study, Vahé Nafilyan and colleagues reanalysed the ONS data, and found that South Asians were more likely to die of Covid than white Brition for almost every combination of wave, country-of-origin and gender. Their results are shown in the chart below. Note: the only combination that didn’t yield a statistically significant difference when including the pre-pandemic health variables (as well as all the others) was Bangladeshi women during the first wave.

In another large study, based on a different dataset, Elizabeth Williamson and colleagues confirmed that South Asians were more likely to die of Covid than white British even when controlling for a large number of different health variables. However, when the same researchers disaggregated South Asians by country-of-origin, they found that the difference between Pakistanis and white British was no longer statistically significant. (The differences remained significant for Indians and Bangladeshis.) Once again, it’s important to note that their model controlled for some factors that might differ among ethnic groups for partly biological reasons.

Vahé Nafilyan and colleagues analysed data on Britons aged 65 and over from the first wave of the pandemic. They decomposed the elevated mortality risk among ethnic minorities into three components: the portion due to household composition; the portion due to geography, socio-economic and health variables; and the unexplained portion. Their results are shown in the chart below: the left-hand panel is for men; the right-hand panel is for women. They found that a non-trivial portion of South Asians’ elevated mortality risk went unexplained.

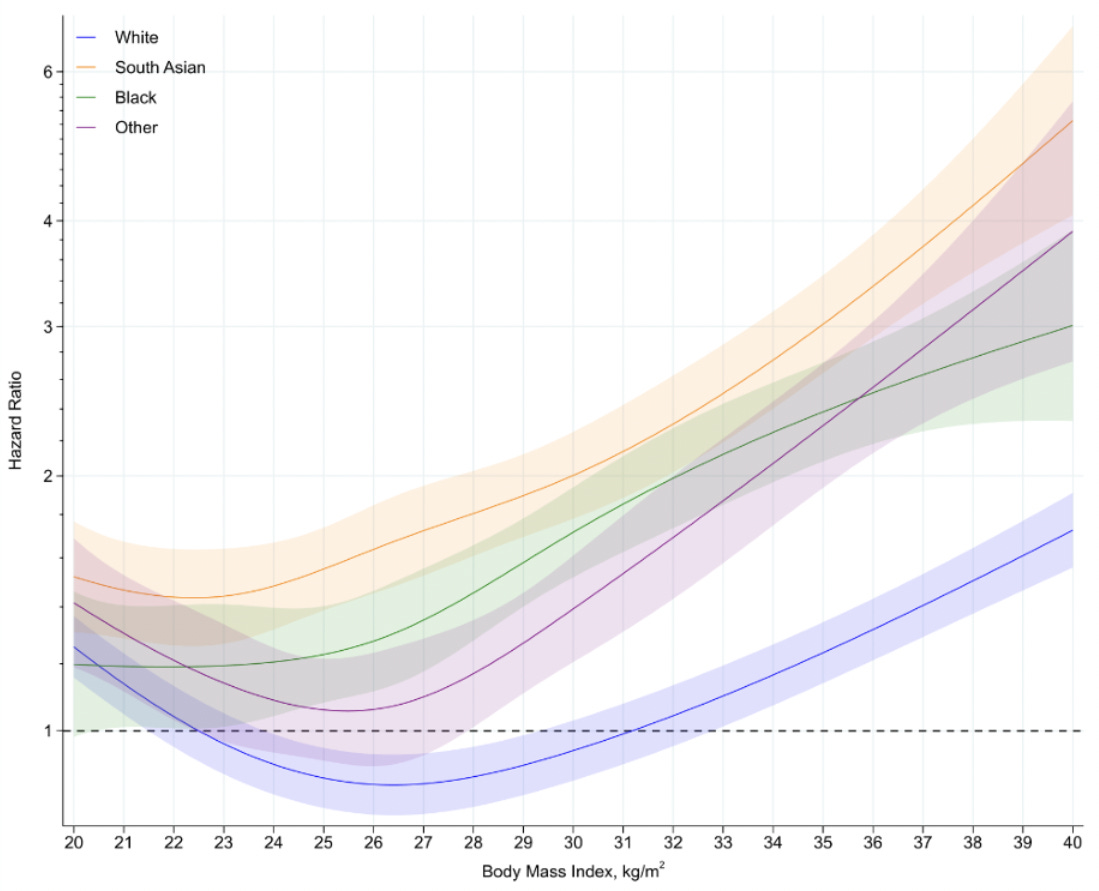

Obesity is an important risk factor for Covid mortality. Thomas Yates and colleagues examined whether the impact of obesity varies by ethnicity. They found that it was substantially larger among ethnic minorities, as shown in the chart below. Whites and South Asians with a healthy BMI were about equally likely to die of Covid. But among those with a BMI of more than 30 (the threshold for obesity), the risk of death was much higher among South Asians. It’s been suggested that some ethnic groups have a stronger inflammatory response to viral infection, and the authors speculate that this may be exacerbated by higher levels of adiposity.

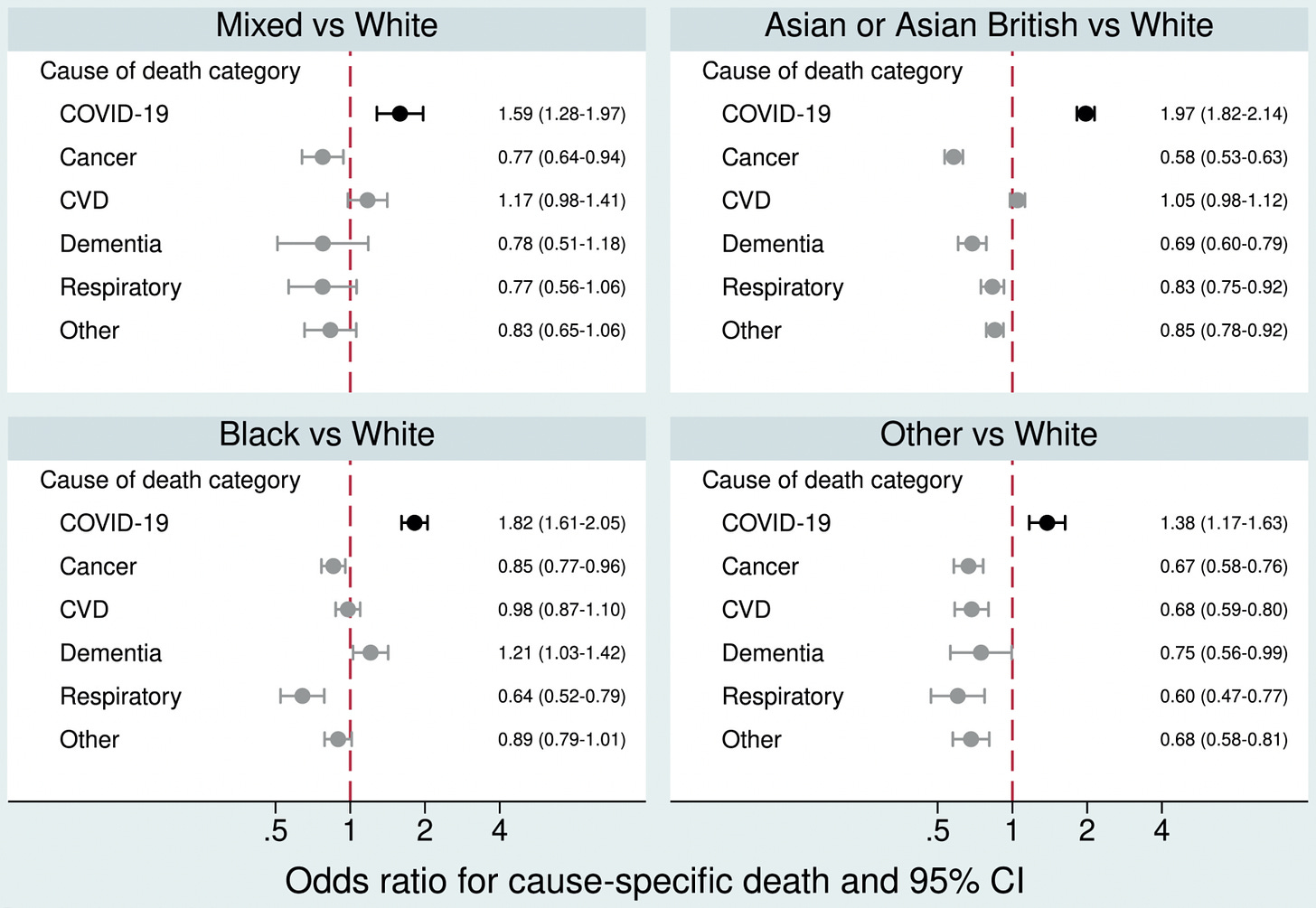

So, several studies have found that South Asians have higher Covid death rates than white British, even after controlling for a range of socioeconomic factors. However, South Asians might simply have higher mortality in general, perhaps because of unhealthy lifestyles or barriers to accessing healthcare. Not so, it seems. Using a large dataset, Krishnan Bhaskaran and colleagues examined the factors associated with Covid death versus non-Covid death. As shown in the chart below, they found that South Asians were more likely to die of Covid but less likely to die of other causes. (The only exception was cardiovascular disease, where the difference was non-significant.)

It should be noted that one major study didn’t find much difference between the IFRs for different ethnic groups, based on data from the first wave. Helen Ward and colleagues estimated IFRs by combining death numbers with estimates of seroprevalence. Their results suggest that the elevated risk of death among South Asians is entirely attributable to higher rates of infection. However, the IFRs have very wide confidence intervals for ethnic minorities (e.g., 4% to 36% for Asian males aged over 65). So the study does not provide strong evidence that IFRs are equal; it merely doesn’t provide evidence that they are unequal. In addition, computing group-level IFRs is less precise than modelling individual data.

Adding to the studies mentioned above is one based on data from Kuwait (all the others were based on British data.) Hamad Ali and colleagues examined patients admitted to hospital for Covid, and found that South Asians had a significantly higher death rate than Arabs when adjusting for age, sex, smoking status and some comorbidities. They conclude that we “certainly cannot overlook the role of genetic factors which might make people from certain ethnicity more prone to severe outcome”.

Aside from studying general population samples, one can look at groups with particularly high exposure to the virus, such as healthcare workers. Lesa Kearney and colleagues identified 193 NHS staff who died of Covid during the first wave. They found that South Asians were substantially overrepresented, as shown in the table below. Interestingly, the overrepresentation of ethnic minorities was most pronounced among doctors and dentists. Of 32 included in the sample, 94% were non-white. Given that medicine and dentistry are high-status professions, it’s hard to see how this figure can be explained by something like deprivation.

All the evidence adduced so far has been circumstantial in nature. The fact that South Asians have an elevated risk of death from Covid when you control for many socioeconomic factors suggests that biology might play a role. But it’s hardly definitive. Is there any more direct evidence? There is some, as I’ll proceed to explain.

Hugo Zeberg and Svante Pääbo showed that a genetic variant associated with severe Covid was inherited from Neanderthals, and today is most common in South Asians – as shown in the map below. The authors note that it “may thus be a substantial contributor to COVID-19 risk in some populations in addition to other risk factors”. However, Prajjval Pratap Singh and colleagues found there was no correlation between the variant’s frequency and the CFR across Indian states. This finding casts doubt on Zeberg and Pääbo’s conclusion; though it’s possible the CFR data available at the time simply weren’t very good.

On the other hand, Damien Downes and colleagues identified what may be the causal gene corresponding to the variant inherited from Neanderthals. They found that the variant is associated with increased expression of LZTFL1. This gene inhibits a process called epithelial–mesenchymal transition, which “plays a key role in the innate immune response”. Downes and colleagues’ findings suggests that the Neanderthal variant’s greater frequency in South Asia may indeed help to explain the elevated Covid death rate among South Asian British.

In a subsequent paper, Zeberg and Pääbo looked at geographic variation in another variant inherited from Neanderthals, this one associated with less severe Covid. However, their findings aren’t particularly relevant to the present question, as the variant is found “at substantial frequencies in all regions of the world outside Africa”. For example, it’s only slightly more common in Europe than in South Asia. Though its absence from African populations could, in principle, help to explain the elevated Covid death rates among Black British.

Sickle cell disease is caused by inheriting two copies of the sickle haemoglobin gene. This gene protects against Malaria in heterozygotes, and is therefore common in equatorial regions. Ashley Clift and colleagues analysed a large UK dataset, and found that individuals with sickle cell disease were significantly more likely to die from Covid – even when controlling for ethnicity. In their dataset, sickle cell disease was twice as common in South Asians than in whites. And it was more than eighty times more common in blacks. So while it could make a small contribution to the disparity between whites and South Asians, it may explain a larger portion of the disparity between whites and blacks.

Okay, but if South Asians really are more susceptible to Covid than white British, why does Britain have a higher Covid death rate than all the countries in South Asia? (See map below.) According to Our World in Data, Britain’s Covid death rate is 2,184 per million, whereas every South Asian country has a rate of less than 500 per million. Bangladesh’s rate is only 168 per million – about the same as Japan.

The first reason is that, for many countries around the world, official Covid death rates are basically garbage. Due to lack of testing infrastructure, the only way to know how many people have died of Covid is by tracking excess mortality. Second, even if the official Covid death rates from South Asia were accurate, you’d expect them to be lower, thanks to population age-structure. The single biggest risk factor for Covid mortality is age, and people in South Asia are a lot younger than those in Britain. For example, the average age in Britain is 41, while the average age in Bangladesh is 27. Obesity rates are also lower in South Asia.

What happens when you compare official Covid deaths to excess deaths for countries without much testing infrastructure? You find a lot more excess deaths. India’s official Covid death toll is 482,000. Yet three recent studies, exploiting several different methodologies, have come up with much higher figures. Lauren Zimmermann and colleagues estimate the number of excess deaths up to June 2021 as between 1.8 and 4.9 million. Abhishek Anand and colleagues estimate 3.4 to 4.9 million, while Anup Malani and Sabareesh Ramachandran estimate 2.8 to 6.2 million.

Taking all the evidence together, South Asians may be somewhat more susceptible to Covid than white British. Though I should stress that, if there is an average difference in susceptibility, it’s not going to be large. Evidence shows that most of the observed gap in death rates is attributable to geography, household structure and other socioeconomic factors. But there does seem to be a small gap left over when you control for these things, which may be partly biological in origin.

As to what specific mechanisms may be involved, we don’t yet have a good idea. Vitamin D deficiency is one I mentioned before, though that hypothesis now looks less promising. (Note: I’d still argue that supplementing makes sense, especially if you have dark skin.) Other possible mechanisms include sickle cell disease; inhibition of epithelial–mesenchymal transition; and the interaction between inflammation and adiposity. What is clear is that the biological basis of Covid susceptibility is a fascinating area of research, with many more discoveries yet to be made.

Image: Colourised transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2

The Daily Sceptic

I’ve written four more posts since last time. The first notes that infection rates are highest in the most vaccinated states, undermining the case for vaccine passports. The second examines whether Omicron came from a lab. The third reports that the Great Barrington authors have hit back against government scientists who tried to discredit them. The fourth notes that a majority of Democrats wrongly believe the vaccines protect better against infection than natural immunity.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.