Yesterday, two committees of the House of Commons (the Health and Social Care Committee, and the Science and Technology Committee) published a long report titled ‘Coronavirus: lessons learned to date’. The report draws on evidence from over 50 witnesses, as well as 400 written submissions, and its conclusions were “agreed unanimously” by the members of both committees. Although the report deals with various aspects of the UK’s response to the pandemic, I will focus here on its discussion of lockdown, which I found to be woefully inadequate.

In short, the report takes for granted that lockdown was the right policy, and in fact argues that Britain should have locked down earlier in March of 2020. It makes no attempt to evaluate the scientific evidence on lockdown efficacy, gives no consideration to focused protection as an alternative strategy, and shows no interest in weighing up the total costs and benefits of lockdown. Indeed, none of the following terms appear anywhere in the report: ‘cost-benefit analysis’, ‘collateral damage’, ‘civil liberties’, ‘focused protection’, ‘Great Barrington Declaration’.

The remainder of this article comprises a point-by-point response to various claims made in the section dealing with lockdowns:

The initial UK policy was to take a gradual and incremental approach to introducing non-pharmaceutical interventions. A comprehensive lockdown was not ordered until 23 March 2020 … This slow and gradualist approach was not inadvertent ... It was a deliberate policy … It is now clear that this was the wrong policy, and that it led to a higher initial death toll than would have resulted from a more emphatic early policy.

I would agree that the UK’s initial policy was “wrong”, but only in the sense that it did not put enough emphasis on focused protection. In the early weeks of the pandemic, we should have emphasised things like: expanding hospital capacity; securing PPE for frontline healthcare workers; separating COVID and non-COVID patients in hospital wards; implementing daily testing for care home staff; and helping elderly people in multi-generational homes to self-isolate.

Of course, when the report says, “It is now clear that this was the wrong policy”, they mean it was wrong in the sense that it was not lockdown. This claim is of course highly contested. The fact that the authors were nonetheless confident enough to write, “It is now clear” (rather than, say, “We believe”) simply shows that they didn’t speak to anyone with the opposite view. Note: I say “anyone” (rather than “any scientists”) quite deliberately. One of the biggest mistakes of the pandemic has been to assume that only scientists are qualified to speak about pandemic policy. As the economist Russ Roberts observes, “Knowing a lot about the human body does not make you an expert in risk analysis, tradeoffs, or unintended consequences.”

As to the claim that “it led to a higher initial death toll than would have resulted from a more emphatic early policy”, this may be true. However, it ignores the fact that suppressing the epidemic in the spring could have led to an even bigger epidemic in the winter, when the NHS would have been under greater pressure. If you have to experience an epidemic, better to get it out the way while the NHS is not under pressure. And indeed, most of the countries in Eastern Europe that managed to avoid the first wave have seen greater excess mortality than the UK, because they got clobbered in the second wave.

It’s odd that the authors ignore this point in the part of the report quoted above because they actually acknowledge it in a later part. Referring to the UK’s initial policy, they write, “Modelling at the time suggested that to suppress the spread of covid-19 too firmly would cause a resurgence when restrictions were lifted. This was thought likely to result in a peak in the autumn and winter when NHS pressures were already likely to be severe.” The authors argue, however, that suppressing the epidemic in the spring bought us time (to develop treatments etc.) And while this may be true, there are obviously arguments on both sides. To suggest it’s “clear” that the UK’s initial approach was wrong is just mistaken.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions such as lockdowns, and the testing and isolation of covid cases and their contacts, are tools of temporary application. Once they are lifted, there is nothing to stop transmission resuming.

While this is true in a sense, it is not an informative way to describe the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2. As Philippe Lemoine notes in his essay ‘The Case Against Lockdowns’ (which contains far more scientific analysis than the House of Commons’ report): “the data show very clearly” that the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 “always starts falling long before the herd immunity threshold is reached with or without a lockdown”. In other words, while lockdowns may have an impact on transmission, case numbers always start falling long before the majority have been infected. There is no reason to believe that, in the absence of lockdown, case numbers would have just continued rising (see below). They stopped rising in Sweden; they stopped rising in Japan. And they would have stopped rising in the UK too.

Exactly what accounts for the timing and duration of COVID epidemics is not yet well-understood. But in addition to lockdowns (whose impact is hard to detect empirically) these factors seem to matter: seasonality; voluntary social distancing; the build up of population immunity to particular COVID variants; and the degree of overdispersion in the distribution of individuals by number of transmission events.

It is striking, looking back, that it was accepted that the level of covid-19 infection in the UK could be controlled by turning on particular non-pharmaceutical interventions at particular times. Indeed such was the belief in this ability to calibrate closely the response that a forward programme of interventions was published with the suggestion that they would be deployed only at the appropriate moment.

Here, the authors are referring to the UK’s initial policy of implementing restrictions gradually and incrementally. And it’s a rather odd thing to read because exactly the same criticism could be made of lockdowns. As David Paton notes in his article ‘The myth of our ‘late’ lockdown’ (which, again, contains much more scientific evidence than the House of Commons’ report), “Our strategy still seems to be based on the discredited assumption that governments can turn infections on or off like a tap by imposing or lifting restrictions.”

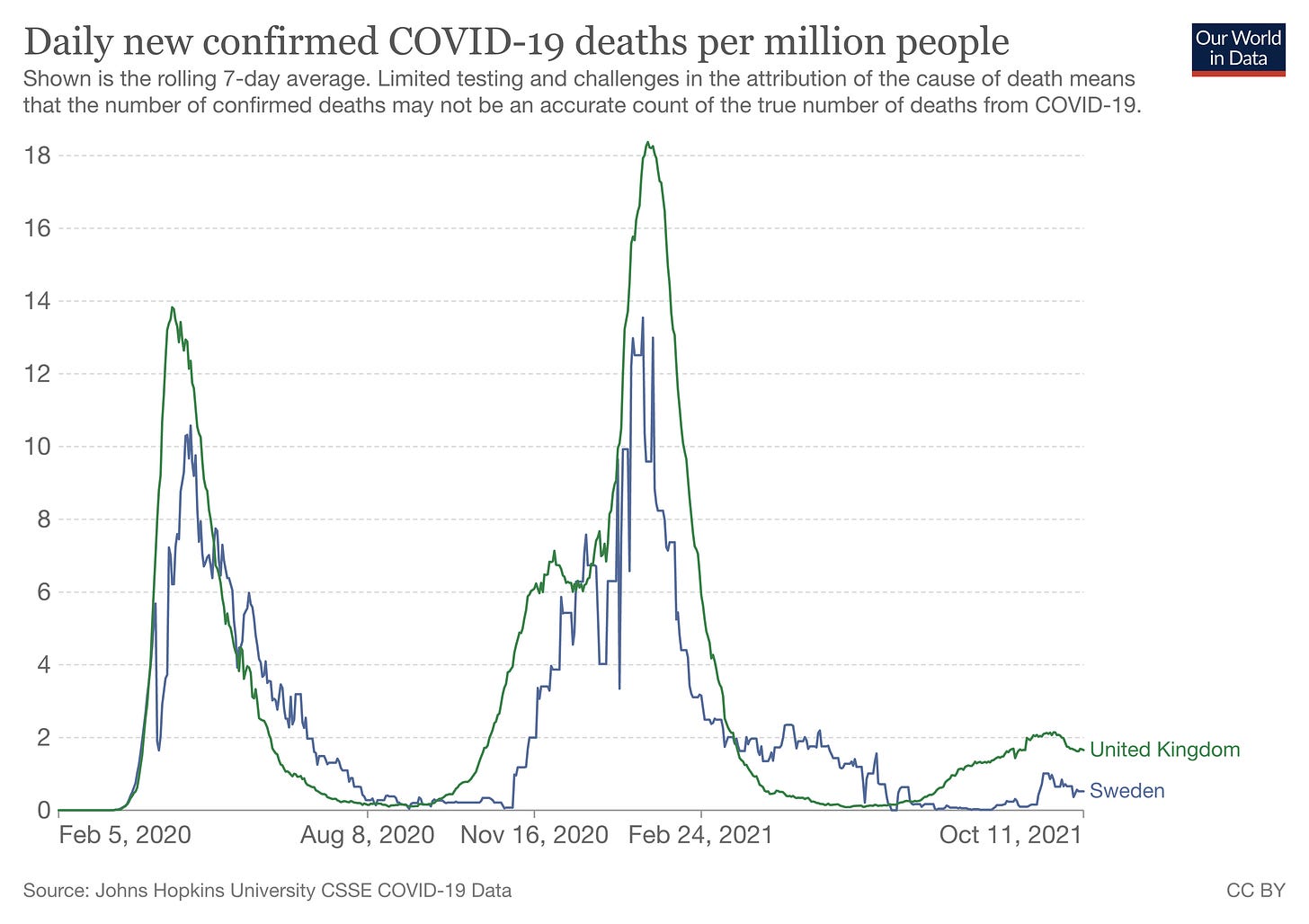

There are places where infections fell in the absence of a lockdown, and there are places where infections rose in the presence of a lockdown. The House of Commons’ report completely ignores this evidence, and assumes there’s a simple one-to-one relationship between lockdowns and case numbers. Peru (which has by far the highest level of excess mortality in the world) imposed a lockdown on 15 March. Yet case numbers continued rising until late August. Sweden, on the other hand, did not lock down, and its death curve looks almost identical to Britain’s.

The UK did not impose blanket or rigorous border controls at the onset of the covid-19 pandemic as compared to other countries, particularly in East and South East Asia … even though it is not straightforward to make direct comparisons between countries, and it is yet to be seen how countries like New Zealand will fare when their borders are opened, it is reasonable to say that a more precautionary approach would have been beneficial at the start of the pandemic.

In my opinion, the case against border controls is not as strong as the case against lockdowns. In fact, I am willing to concede that combining short early lockdowns with strict border controls may have been the best approach for geographically peripheral countries like Norway, Finland and New Zealand. (I wrote an article back in February arguing that lockdowns only work if you lock the borders down too.)

However, I do not believe this approach was feasible for the vast majority of countries, especially not large, dense, highly connected countries like the UK. And even if we had managed to contain the virus in the spring of 2020, this might have simply postponed the epidemic until the winter, when the NHS would have been under greater pressure (as I’ve already noted). Therefore it is not necessarily “reasonable to say that a more precautionary approach would have been beneficial at the start of the pandemic.” Assuming that what was practical for New Zealand would have been practical for the UK is myopic to say the least.

The restrictions eventually imposed on the UK public because of the pandemic were unprecedented. Even in wartime there had been no equivalent of the order to make it a criminal offence for people to meet each other and to remain in their homes other than for specified reasons.

There’s nothing to disagree with here. The reason I included this quotation is to highlight just how far-reaching and unprecedented the UK’s lockdown measures were. As I mentioned in the introduction to this article, the House of Commons’ report makes no real attempt to gauge the costs and benefits of lockdown, including the difficult-to-quantify but hugely important costs of suspending the entire population’s civil liberties.

The authors might reply that a large majority of British people supported the lockdowns, which is true. However, this is partly because their perceptions of the risks of COVID were so skewed. As David Spiegelhalter and George Davey Smith noted last year, “the notion that we are all seriously threatened by the disease” has led to “levels of personal fear being strikingly mismatched to objective risk of death”. (People overestimating the risks of COVID is much bigger problem than people assuming it’s “just the flu”.) And I would conjecture that part of the explanation lies in the government’s policies and messaging.

Although introduced several weeks after it should have been, the national lockdown brought in on 23 March succeeded in reducing the incidence of covid across the country, so that from May 2020 national restrictions were eased.

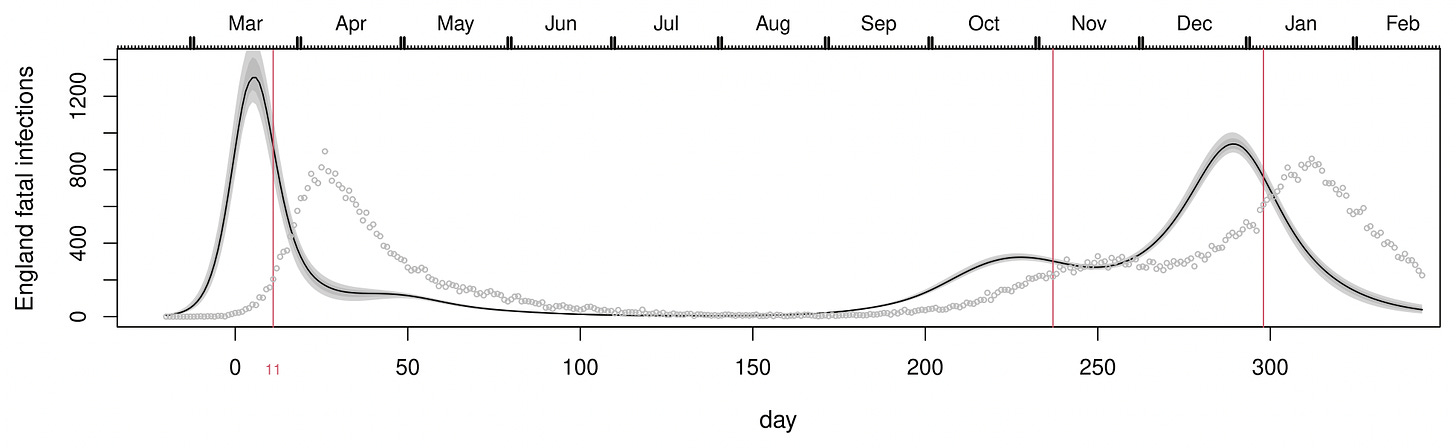

This is at best a matter of significant dispute, and at worst simply false. We do not have good data on infection numbers from the spring of 2020. However, two high-quality reconstructions of the epidemic curve suggest that infections peaked before the lockdown on March 23rd. The first reconstruction (shown below) was made by the statistician Simon Wood, using data on daily hospital deaths and the distribution of fatal disease durations. His analysis suggests that “fatal infections were in decline before full UK lockdown” and that “fatal infections in Sweden started to decline only a day or two later”.

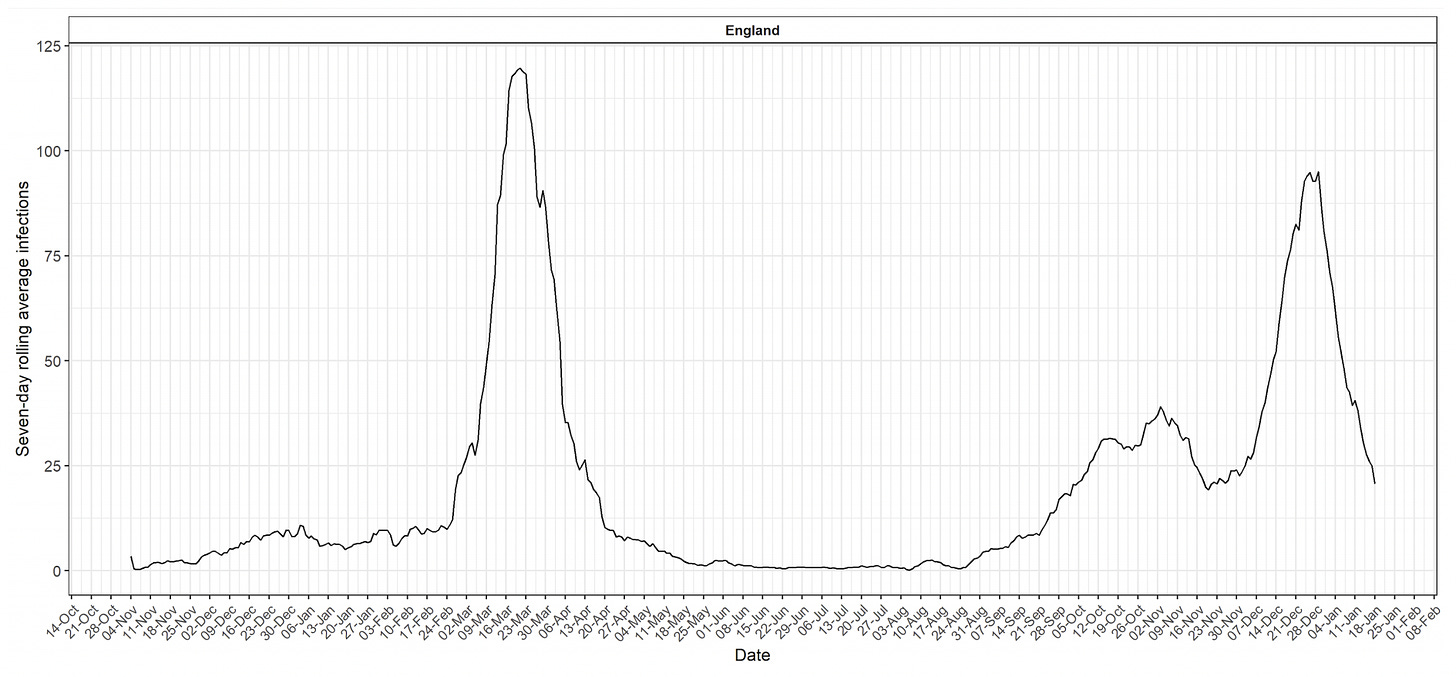

The second reconstruction (shown below) was made by the researchers on Imperial College’s REACT study – a repeated cross-sectional survey in which individuals who test positive for COVID antibodies are asked when their symptoms began. As Will Jones notes, it’s a particularly useful chart because it doesn’t rely on data from PCR tests, which sometimes yield positive results even after the individual in question is no longer infectious. (This may explain why the waves are slightly narrower than we’re used to seeing.) As in Simon Wood’s chart above, the peak of the first wave – if you look carefully – occurs several days before the national lockdown.

What’s more, both of these analyses are consistent with remarks made by Chris Whitty to the Health and Social Care Committee last spring. (The Committee must have forgotten to include these in its report.) As The Times notes, “The coronavirus pandemic was probably already in retreat before the full lockdown was imposed, the chief medical officer for England said”. Overall, there is strong evidence that cases were falling by March 23rd, so it’s false to claim the lockdown “succeeded in reducing the incidence of covid across the country”. Of course, this isn’t particularly surprising. We know that Sweden’s epidemic began to retreat around the same time as the UK’s, and Sweden didn’t lock down.

The discussion of lockdown in the House of Commons’ report is shoddy and tendentious. Concluding that lockdown was the right policy is one thing. But not even bothering to address the case against it is quite another. Aside from a few quotations and vague references to the success of East Asia, the authors don’t even bother to lay out the case for lockdown. (Japan, by the way, didn’t lock down at all in 2020.) They simply assume it was the right thing to do, and don’t get bogged down in messy details like whether the costs might have massively outweighed the benefits.

This is not to say, incidentally, that the UK’s original plan was flawless. Although it was in some sense a focussed protection strategy, it paid far too little attention to the protection part. Rather than scrambling to put red tape over park benches and interdicting ramblers in the countryside, the government should have focussed its efforts on hospitals and care homes, as well as elderly people in multi-generational homes. I do not find it plausible, given everything we know, that achieving some degree of focussed protection would have been more onerous than locking the entire country down.

Image: The Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2008

The Daily Sceptic

I’ve written four more posts since last time. The first argues that firing unvaccinated healthcare workers who don’t have natural immunity is mean-spirited and unnecessary, while firing those who do have natural immunity makes no sense at all. The second summarises a recent study finding that natural immunity is still present 12 months after infection. The third argues that preventing COVID infections among healthy children is pointless. The fourth responds to recent hit piece against the Great Barrington Declaration.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.

Excellent. There have been some weird takes. Like the “Female leaders are doing better at controlling Covid” and referencing NZ, Finland, Iceland, and a couple others I don’t recall. (Maybe Germany’s Mutti, but if so that’s been well and truly demolished).

That was always crazy, but so many crazy things. Yet one of the really *Not Crazy* things, like the GBD, are ignored or smeared.

Really! [Smack’s forehead]

Noah: you write well, clearly and cogently. I love it!