A response to Curtis Yarvin on the pandemic

In a recent Substack post, the neoreactionary blogger Curtis Yarvin doubled-down on his earlier advocacy of Zero Covid. While this was not an unreasonable position to hold in April of 2020 when Yarvin penned his original post, it has long since become untenable. (I myself was pro-lockdown until Sweden’s epidemic began to retreat, and it became clear that initial projections concerning what would happen in the absence of lockdown were completely wrong. You live and learn.) Although Yarvin’s post has already received a lot flak, I wanted to offer my own critique. What follows is a point-by-point response.

Note: although I don’t read Yarvin regularly, as I find his writing style too cryptic and his posts too long-winded, there can be no doubt that he’s an interesting and important commentator. Hence I don’t believe, as some exasperated critics have suggested, that he should be written off due to his views on Covid. In fact, given that he must have known his post would raise some hackles, the man deserves credit for being intellectually honest.

Further note: I’ve seen it claimed that Yarvin’s post was really an exercise in “4D chess”, or an attempt to teach his readers some kind of lesson about truth and power. That’s possible, though to be quite honest I haven’t read enough of his work to say whether it’s likely. (Based on what he said back in April of 2020 – at a time when non-literal interpretations wouldn’t make much sense – I can easily believe the post reflects his real views.) Nevertheless, here I’ll respond to the straightforward, literal interpretation of what he wrote.

The mortality rates of covid for younger populations do not justify emergency governance measures; the morbidity rates for middle-aged populations do … While boomers may be a net liability, it seems that a substantial percentage of middle-aged people do experience serious health damage.

I am not aware of any evidence that a “substantial percentage” of middled-aged people experience “serious” health damage. Some surely do, and that is regrettable, but the numbers certainly don’t justify “emergency governance measures”, particularly since such measures have proven to have at best only a small impact on the epidemic’s trajectory. (I will get to China’s “successful” lockdown later.) Moreover, “emergency governance measures” themselves can lead to morbidity further down the line by causing social isolation or by disrupting healthcare provision.

If Yarvin is referring to “long Covid” in the quotation above, the latest evidence suggests that its frequency has been massively exaggerated. It was initially believed to affect about one in every ten people who catch the virus. Yet a recent analysis by the UK’s Office for National Statistics, based on a large random sample, found that only 2.5% of people still report symptoms after 12 weeks. However, even that number may be an overestimate, since it assumes that every participant reported their symptoms accurately.

One French study asked a large number of people who were tested for Covid antibodies whether they’d experienced each of 18 different symptoms (see above). They found that individuals who believed they’d been infected were more likely to report symptoms. Yet with the exception of anosmia, those who’d actually been infected were not. The French study suggests that there’s a psychosomatic component to long Covid. And it’s consistent with earlier studies from Germany and Switzerland finding that self-reported long Covid wasn’t much more common among young people who tested positive than among those who tested negative.

This is not to say that nobody gets lasting symptoms after a bad Covid infection – some surely do – just that the scale of the phenomenon has been exaggerated. Those who had reason to believe they would get such symptoms should have been encouraged to self-isolate until such time as vaccines and/or treatments became available.

A world of Singapores might look like a country whose covid graph looks like this … Strangely, there is only one such country. But it is a big one. It proves that controlling this virus is possible. And for those who value their freedoms™, subjects of China live today with far fewer covid restrictions than citizens of the reddest American red state.

To begin with, it’s patently untrue that people in China live today with “far fewer” Covid restrictions than their counterparts in the “reddest American red state”. When it comes to Covid, the reddest American red state is arguably South Dakota, whose libertarian governor Kristi Noem refused to lock down, claiming that the “people themselves are primarily responsible for their safety”. That was back in April of 2020. As of October of 2021, China is still locking down cities of 4 million people after finding six cases.

But does China “prove” that controlling the virus is possible? Maybe. If we assume that their numbers are correct (which is a big assumption), it shows that a brutal lockdown can temporarily suppress the virus. What it doesn’t is show that the overall benefits of suppression outweigh the costs, or that a China-style lockdown would have worked in large Western countries like Britain and America.

Take Britain. Suppose that we’d undertaken a China-style lockdown in February of 2020. That would have meant locking most people in their homes, while arranging for teams of delivery drivers to drop off essential food and medicines. Put aside the colossal economic damage and unprecedented violation of civil liberties this would have entailed. What would have been the effect? Well, infections in the spring of 2020 would have presumably been kept to a minimum. But in order to prevent them from rising again, strict border controls would have been required.

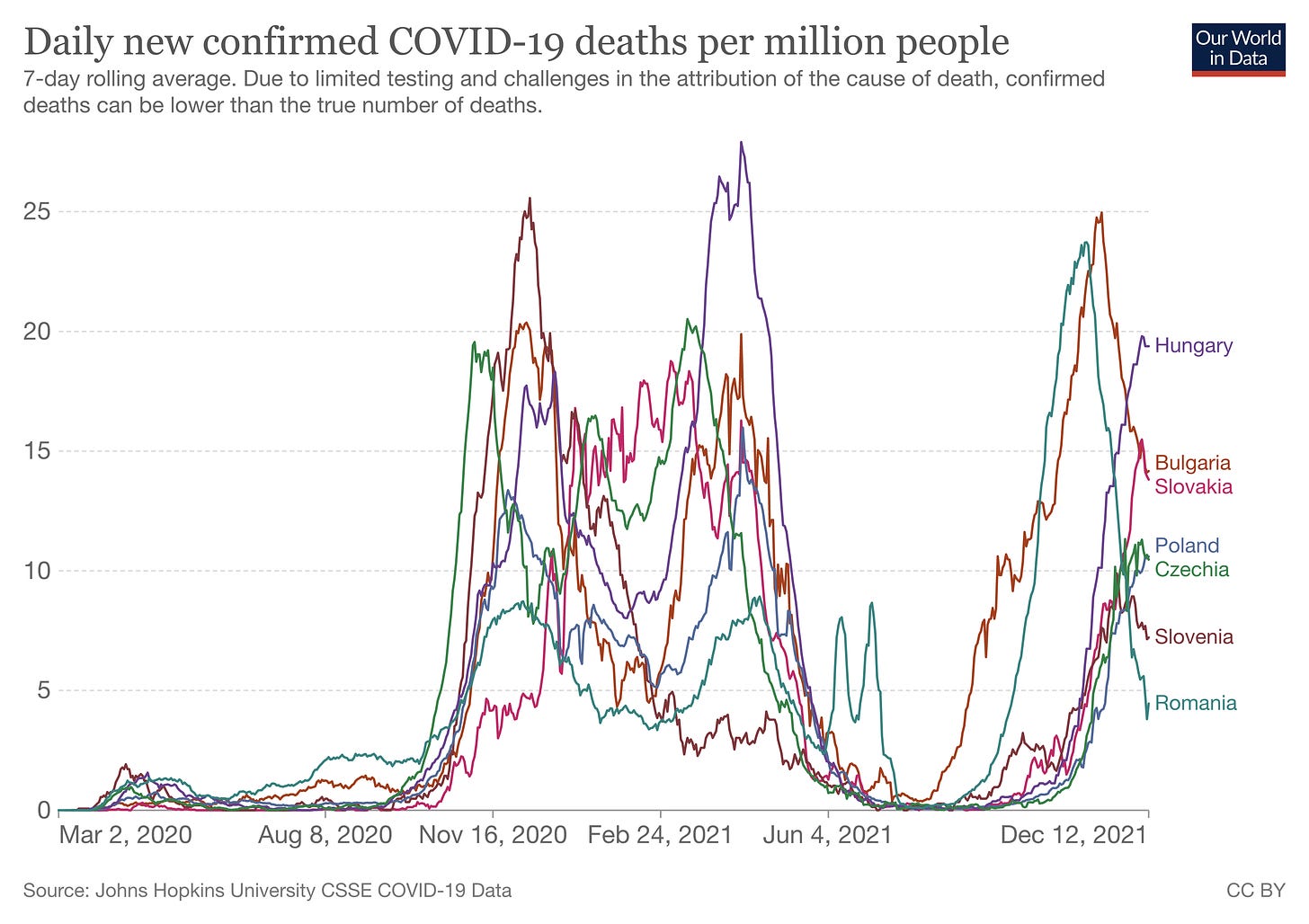

That would have meant imposing a permanent quarantine system, making overseas travel all but impossible, and completely decimating the tourism sector. What’s more, it would have been extremely risky. By suppressing the epidemic in the spring, we would have created the conditions for an even bigger epidemic in the winter. Note: European countries that dodged the spring wave have actually had greater excess mortality, since they got hit even harder in the winter wave. This makes sense, as healthcare systems are usually under more pressure in the winter (see below).

But suppose we’d managed to prevent another epidemic from burgeoning in the winter. I’m assuming we’d then have lifted the restrictions in the spring, once offered everyone had been offered the vaccine. All in all, that would have meant living through a full year of lockdowns and travel restrictions just to prevent the age-standardised mortality rate falling to the level of… 2008. Note that in the year before the pandemic, 91% of the world’s population lived in countries with a higher mortality rate than this.

And that’s making the very generous assumption that we’d actually been able to forestall a winter epidemic. More likely, we’d have ended up in an even worse position where a huge number of infections occurred during the NHS’s busiest months.

And as for the opposition theater which is the opposite school of governance theater—it is even worse. Its theater makes no sense and could not even be put into practice, at least not as a general policy. In this case it would lead to a Scandinavian covid policy, which is tenable. But accidentally tenable. With a much worse virus—or a much worse covid variant, perhaps one as deadly as SARS-1—it would not be tenable.

By “opposition theatre”, I believe Yarvin is referring to the recommendations of lockdown sceptics like myself and, more significantly, the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration. Though he concedes some ground by describing our preferred policy as “accidentally tenable”, he goes on to claim that with a much worse virus, “it would not be tenable”.

I agree, and that’s exactly the point. The characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 – airborne, highly transmissible, and with low mortality rate for most of the population – make suppression a very unattractive approach, as numerous pre-pandemic documents testify. For example, a 2019 report published by the John Hopkins Center for Health Security notes, “Quarantine measures will be least effective for pathogens that are highly transmissible, have short incubation periods, and spread through true airborne mechanisms”.

Hence the focused protection strategy outlined in the Great Barrington Declration is not “accidentally tenable”. It is tenable in virtue of the characteristics of the pathogen we’re dealing with. If there was an outbreak of a much less transmissible, much more deadly pathogen, a different approach would be called for.

There is no reason that every country has to be sharing every other country’s viruses. The world did not need a Delta epidemic; only India did. The world did not need an Omicron epidemic; only South Africa did. Punishing other countries does not help any country which experiences such bad luck—except maybe in a theatrical sense.

The costs of permanently sealing international borders until the “end” of the pandemic (whenever that might be) would almost certainly have outweighed their supposed benefits. Once again, those who were particularly concerned about catching Covid should have been encouraged to self-isolate until such time as vaccines and/or treatments became available.

Seeing like a state means that the regime knows exactly who is inside its borders. For every biped not a bird or kangaroo, the state has a biometric record and a general, low-frequency idea of the beast’s location. In a pandemic, the state needs a precise, high-frequency idea of everyone’s location—since it needs to know who is infecting whom. The state has always been defined as a shepherd. The modern shepherd gets an alert and a photo every time one of his sheep takes a shit.

Contact tracing has only really worked in East Asia. And there’s good reason to believe that East Asia’s “success” could not have been replicated in the West – outside of those geographically peripheral countries like New Zealand and Iceland that have basically shut themselves off from the world.

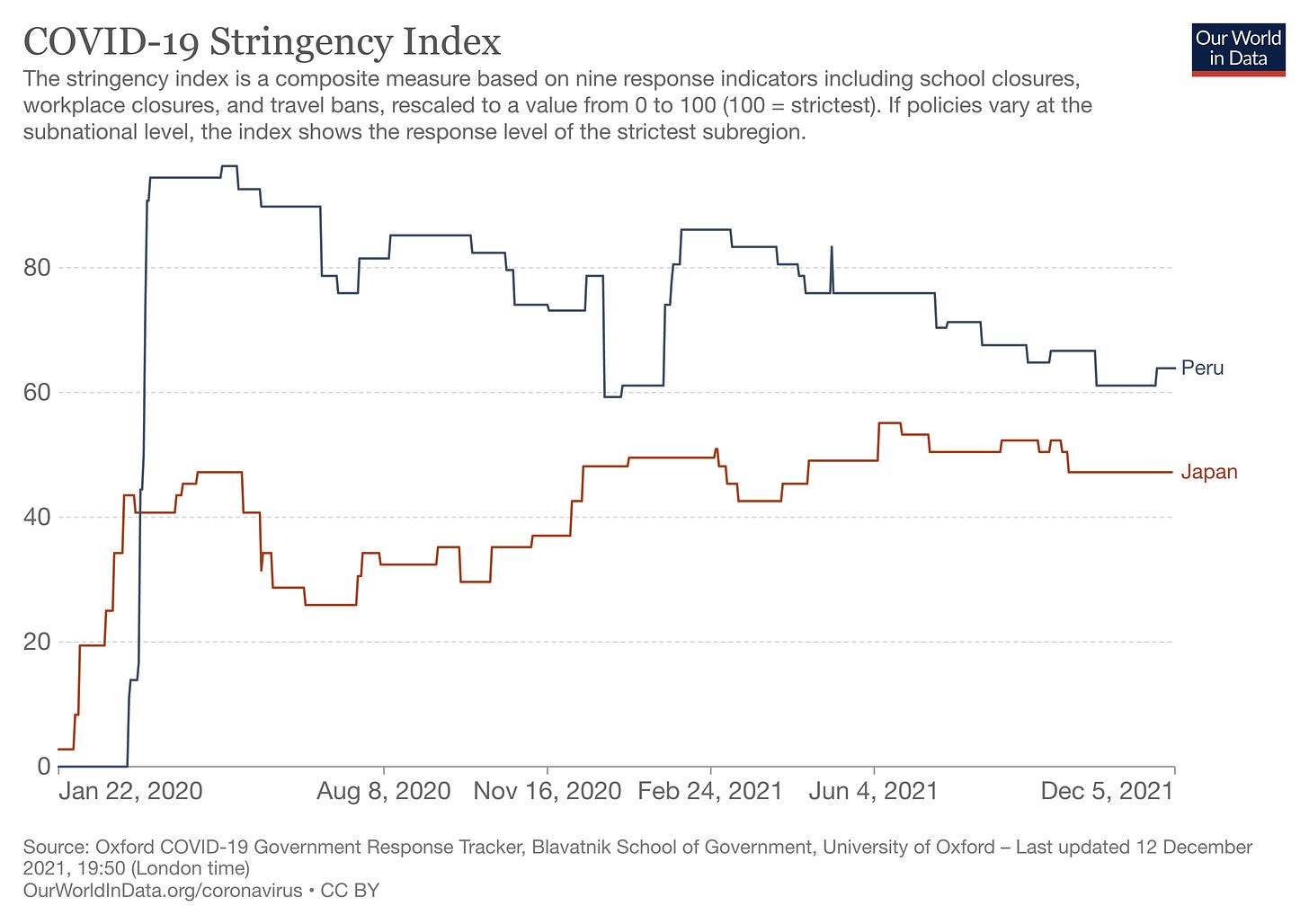

As I noted in my post ‘Why have there been so few COVID deaths in Japan?’, the answer isn’t that they used draconian lockdowns and rigorous contact tracing. Because they didn’t. In 2020, each of Japan’s waves retreated without any real lockdown measures being imposed. (There were zero days of mandatory business closures and zero days of mandatory stay-at-home orders.) This suggests that some cultural or biological factor explains the country’s success – and perhaps the whole region’s. One plausible candidate is greater prior immunity.

Note that no country in East Asia has had more than 4% excess mortality since the pandemic began, with Japan’s figure being just 1%. (By contrast, excess mortality in Peru is running at 173%.) This is despite the fact that Japan made almost no attempt to suppress the virus, and even hosted the Olympics earlier this year (see above). So unless you believe that China, Taiwan and Singapore are more similar to the West than they are to Japan, its reasonable to assume that what they did wouldn’t have worked over here.

One urban myth of political science rife in the Western mind, past and present, is the myth that the powers of government can be mechanically restricted, or that such restrictions can produce better, fairer or less intrusive governance. It is this myth that stands tall in the citizen’s mind when he denies the pandemic command center his location, even if that same location is currently rented to every spammer in Albania.

Yarvin’s right that restricting the powers of government doesn’t necessarily produce better governance. But it’s going to take a lot more than that to convince me that handing governments the power to track our movements is a good idea. Even if it could have helped during the pandemic (which I doubt), there’s the real possibility it would be misused in the future. As economic historian Robert Higgs has noted, government powers seem to accrue via a “ratchet effect” whereby they’re very hard to get rid of once you’ve got them.

Everyone has to brush their teeth every day—or should. It is not a giant human-rights violation for everyone’s morning routine to include a simple covid swab—especially since this is not a permanent imposition, but a wartime measure in a victorious war.

Repeatedly testing everyone for a virus that simply cannot be eliminated sounds like a monumental waste of resources. A far better use of those swabs would be daily testing of care home and hospital staff, as a way to protect high-risk groups.

Covid is a generalist virus and animal reservoirs will remain. Every once in a while, a deer hunter may get covid from a deer. These little outbreaks should produce a prompt, effective, and mandatory contact-tracing and contact-testing response.

Contrary to Yarvin’s earlier statements, this seems to imply that contact-tracing would be a permanent fixture of our lives in his Zero Covid regime – since the animal reservoirs aren’t going away. And what if one of these contact-tracing responses fails, and we get another global pandemic? Do we start the whole cycle of lockdowns all over again?

Once the virus had made its way from Wuhan to all four corners of the globe, it was destined to become endemic. You can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube. And you can’t put the highly infectious respiratory virus back in the lab (or animal market). However, there’s no reason to fret about Covid becoming endemic. We’ll all have acquired some immunity to it by then, whether through natural infection or vaccination. And our treatments will also have gotten better. Eventually Covid will be just another seasonal respiratory virus.

For a man who made his name dissecting the contradictions and untruths at the heart of progressive politics, Yarvin’s views on Covid betray a surprising credulity for the “conventional wisdom”. And even the conventional wisdom seems to be incorporating the lesson that Zero Covid could never work; albeit rather slowly. Once you step back and realise that the worst thing about Covid was its novelty (i.e., the fact that very few of us were immune) it becomes clear that our task was managing the transition from pandemic to endemic, without destroying society along the way.

Image: New York, United States, 2017

Obesity passports

I wrote a piece for RT pointing out that the latest argument for vaccine passports implies we need obesity passports too. Here’s an excerpt:

Suggesting that unvaccinated people should be punished for their “fear, ignorance, irresponsibility or sheer stupidity”, in the words of Andrew Neil, is essentially an argument for privatised healthcare. Why should people who’ve made the ‘responsible’ choice (in this case, getting vaccinated) have to pay for those who haven’t? … It’s therefore quite strange that leftists have been making similar arguments. I guess the urge to chastise your political opponents sometimes overrides your commitment to long-standing values, such as socialised healthcare…

The Daily Sceptic

I’ve written four more posts since last time. The first summaries a recent study finding that natural immunity protects better against infection than the Pfizer vaccine. The second argues that the NHS Covid Pass doesn’t make any sense. The third notes that there isn’t any hint of a negative association between the stringency index and excess mortality in Europe. The fourth summarises yet another study finding that natural immunity protects better against infection than the vaccines.

Thanks for reading. If you found this newsletter useful, please share it with your friends. And please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already.